|

Читайте также: |

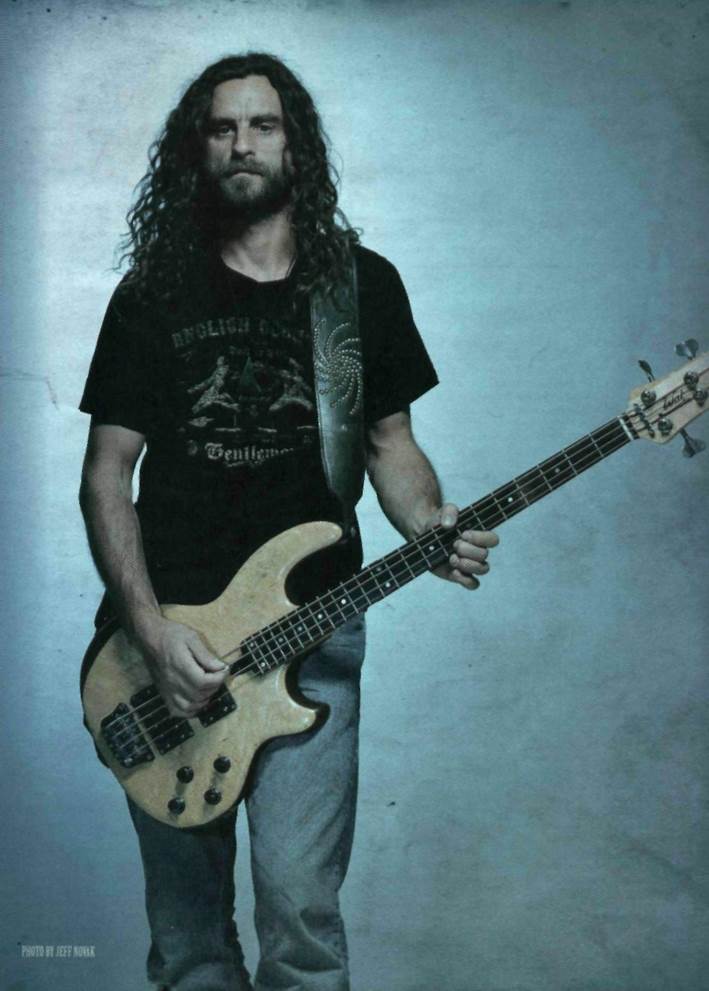

IT WAS A VERY WATERY YEAR FOR ME, in the best way," jokes Justin Chancellor, referring to the twin pursuits of sailing and surfing he took up after Tool wrapped their last world tour in late 2002. For the now-34-year-old bassist, hitting the breakers wasn't too much of a stretch; back in the early '90s he was an avid skateboarder, and the quiet Topanga, California, community where he lives today is only minutes from the beach.

"Here in L.A., it's great to be able to just get in a boat and leave the land for a while. When I first listened to the new album all the way through, just a couple of weeks ago, I was out in the middle of the bay. It's a relaxation thing, and it's hard to nail down how it interacts with the music, but it definitely does."

There's certainly an initial sense of the oceanic in much of the dark, voluminous wave of sound that undulates through 10,000 Days, Tool's first studio album in nearly five years. But, as is the case with their multilayered, rhythmically complex, hard-driving, acid-fueled metal, the band members are chasing more than just first impressions. For Chancellor himself, the album presented an opportunity to flex his chops — from the aggressive pick attack for which he has become known to the newfound forays into finger-plucking that he displays on the title track. Always ready for just about anything, this is one bassist who has his ears tuned to the most genre-defying and progressive movements in music today but isn't afraid to tap his childhood

|

influences (among them Pink Floyd, King Crimson, and Gong) for a bit of the unexpected.

Chancellor's sound begins with the active pickups in his four-string bird's-eye maple and mahogany Wal bass, which he bought shortly after joining Tool in 1995 for the rehearsals that would lead to the completion of AEnima. At the time, his main bass was a Music Man StingRay he'd used with the Brit prog-psychedelic band Peach, but there was something about the instrument that wasn't capturing the punch of original Tool bassist Paul D'Amour (who by then had left die band amicably to pursue his own musical direction with Lusk).

"The StingRay tended to disappear on the faster songs," Chancellor explains, recalling his attempts to duplicate the blistering lines D'Amour had laid down for such tracks as "Bottom" from Tool's 1993 breakthrough, Undertow. "I'd get a rumble at the bottom, a little click on the top, and nothing much in the middle. When we were tracking for AEnima, Ken Andrews from Failure - he's a friend of Adam's — was in the studio and happened to mention that he always thought a Wal would be great with Tool. So he brought [ex-Failure bassist] Greg Edwards' ax with him and told me to give it a go, and it immediately stuck. I ordered one from England and I haven't looked back since."

In the studio, Chancellor has always opted for a three-pronged approach to recording. On Lateralus, his setup consisted of Mesa/Boogie amplifiers-an M-Pulse with ProCo's Turbo BAT for slight distortion (with a Boss rack EQ to boost the low end) — and an older M-2000 running clean, with both amps firing up ultra-sturdy Mesa/Boogie 8x10 RoadReady bass cabinets. The third channel took advantage of the Wal sound itself running direct to the mixing board through a Demeter VTBP-201S tube preamp. Before sessions began for 10.000 Days, Chancellor took a slight leap of faith, making what some would consider a radical equipment adjustment.

"1 went and jammed with Isis," he recalls, naming another genre-busting L.A.-based band whose 2004 album, Panopticon, features a guest appearance from Chancellor, "I showed up at their space one day and they had these Gallien-Kruegers in there, which I ended up playing through. They just realty gave me something that I'd been missing—I'd call it a more direct punch. I'd always had a bit of trouble getting a real hot signal that didn't completely break up and get all fluffy and distorted, and I've found that with the G-Ks, I can get a much purer, cleaner sound at a higher volume."

Even after switching amplifiers, Chancellor was still willing to submit to another sustained dose of controlled chaos. Once he got in the studio with Barresi, he consented to open the floodgates to an entirely new palette of sonic possibilities. "There was a lot more experimentation," he explains, "but there was also a lot of care taken before we actually committed to a sound. Joe brought in all the cabinets we could get our hands on - he had an old Ampeg, a bunch of different amps — and we tried every single combination, just mixing and matching. Finally, we just eliminated everything other than the Boogie cabs and the G-K heads."

From there, Barresi suggested tweaking the distorted channel on the bass - a move that can be heard to stunning effect in some of the harder sections of songs like the odd-metered "Jambi" and the funky, hook-laden anthem "The Pot." It rears up with particular vengeance when Chancellor's DigiTech Whammy pedal kicks in, which has gradually become a staple of his sound; discerning ears will detect it, for example, on the fretless Wal bass line weaving a humid path through "Rosetta Stoned"-yet another vehicle for Chancellor to push his creative envelope.

"On Lateralus, I think I was afraid of having too much distortion going on," he explains. "I just wasn't sure if that would ever be used or if it would really work. But Joe wanted to muddy it up even more, and we could really hear that in the mixing stage. I've found that sometimes you listen to a song, and you can hear the bass in there and it sounds pretty clean, but if you strip everything away, it's actually pretty muddy. I think a lot of bold '70s stuff was like that, and obviously Joe knew that could be the case. So you kind of have to go with the expert, you know?"

Chancellor didn't just opt for change concerning his equipment and sonic perspective: he also branched out with his technique. Ever since he started playing bass at age 14 he had always wielded a pick, but the epic title track

"10,000 Days" made other demands. In sections where Jones and Carey fill the song's wide-open psychedelic spaces with feedback washes and cascading fills (augmented by Keenan's beautifully creepy vocal intonations), it's up to Chancellor to hold everything together with a hypnotic, repeating bass figure. "1 think we were just messing around, and I started plucking the strings like you would an acoustic guitar," he says. "Adam said he liked the sound of it, so it started like that"

| DANNY CAREY |

Chancellor's early interest in orchestral music had drawn him to classical guitar when he was a kid, but he hadn't tried to play in that mode in ages. "I've always felt really insecure about watching other bass players who could just slam with their fingers," he admits. "I'd never really tried it, and I wanted to be able to do ft. So I literally spent all year taking that on as a learning exercise. The only way of getting it together was to play it every day. You sound horrible to start with, and then eventually you find muscles you didn't know you had. Just getting through the song the first time felt so good, because there arc a lot of big stretches in it. I even had to sit down to get it — which will be another challenge when we play it live. I'm not really down with having the old stool come out!"

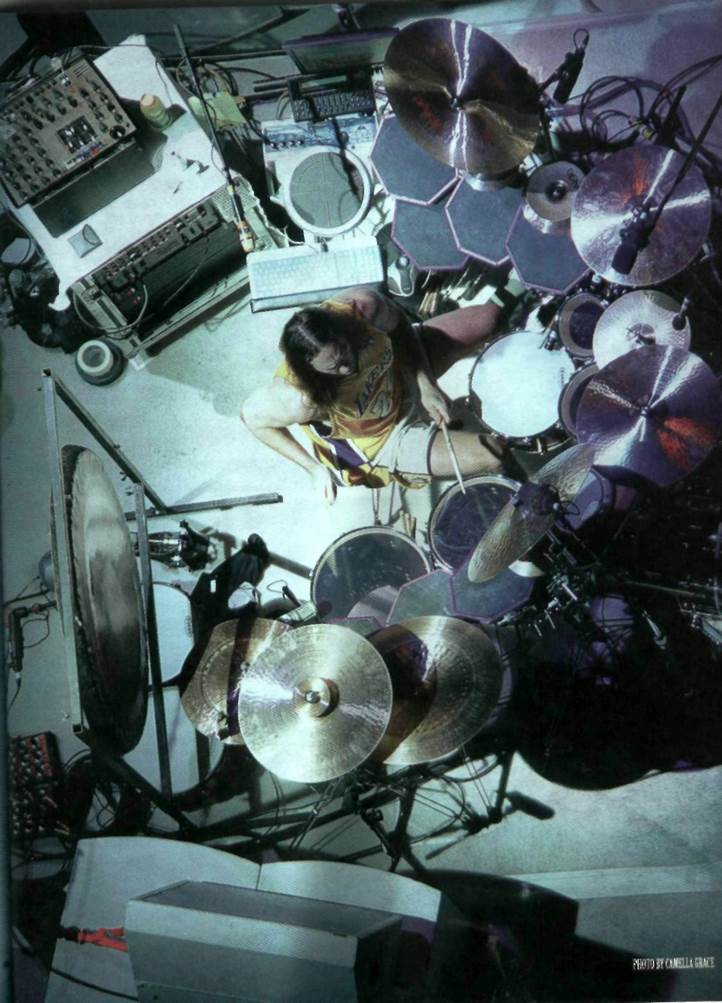

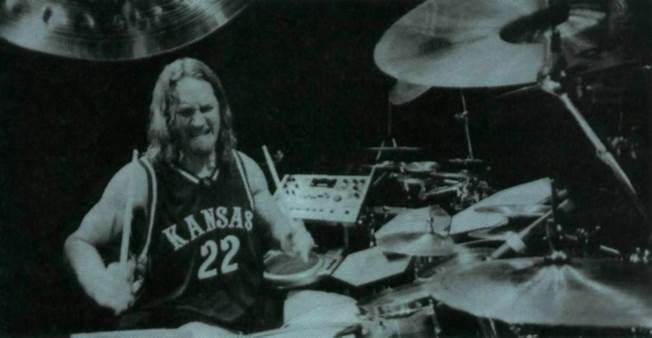

WHEN WE LAST SPOKE WITH Danny Carey in his Los Angeles studio, the six-foot-plus drummer was surrounded by a cabal of questionable objects. An enormous "Enochian magic board" sat behind his drumset, cobwebbed skeletons and a large geometric grid hung from the ceiling, dinosaur mobiles and a 100-year-old sword cluttered a coffee table. But five years after the mighty mayhem of Tool's Lateralus. Carey is spending more time in the light than in the dark (his once-murky studio is now the band's Apple Mac-equipped rehearsal space), with enough extracurricular projects to shake a magic wand at.

"It's been a brutal ride finishing 10,000Days," a re-energized Carey says from Tool's management offices in Hollywood. "Thank God we knew there was a payoff at the end. But it was a long process. Every time one of us would bring in a riff or a song idea...that idea is like your little baby, and then you'd just sec it drawn and quartered. It can be a disheartening process. But the beauty of it is that 95 percent of the time, the idea evolved into something much better than how you first envisioned it. It was a sacrifice worth making, and we all know that. That's what makes us a band."

On 10,000 Days, Maynard James Keenan, Adam Jones, Justin Chancellor, and Carey used various paths of self-exploration to create their most jaw-dropping work to date. 'The theme of the album is growth and communication," Carey explains. "But we're more cynical this time than on our last couple of records. We're angrier about the state of affairs worldwide. A threat you can't escape is running through all our lives."

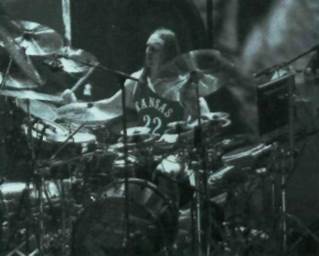

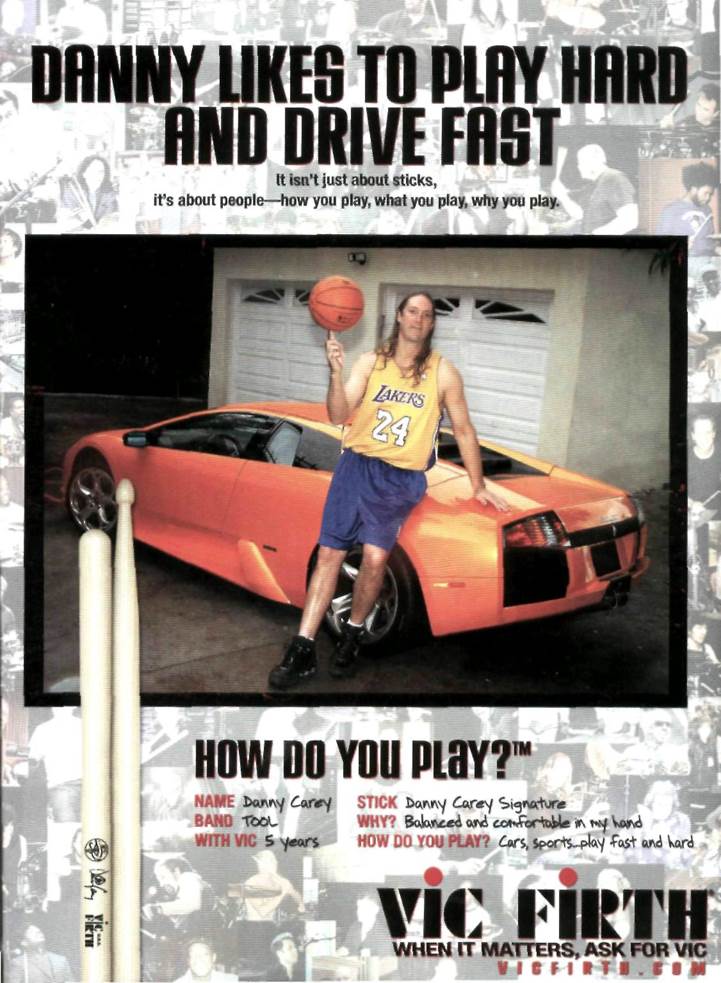

While the other members of Tool worked on their individual parts, Carey got busy recording with electronic marauders Skinny Puppy (2004's 'The Greater Wrong of the Right) and working around town with fusion revivalists Volto! To blow off steam, Carey also joined the NBA Entertainment League, where he plays with fellow basketball fanatics George Clooney and Lit' Bow Wow.

Care)' developed new recording methods for 10.000 Days, such as filling

|

the studio with helium and playing his self-designed Mandala electronic pads for sampled effects. Carey's recent tabla studies have also affected the band's music, as has his distinct lack of individual practice. And by playing a set of Designer Series Sonor drums that were built to his exact specifications, Carey was able to express his drumming soul as never before. But certain nagging questions remain. Will Carey ever record a solo record, cut his own instructional DVD, or tour as a solo/clinic artist? Honest to a fault, he will answer your questions. But whatever you do. don't ask Danny about "those monkey show clinics." He just might tell you the truth, or cast you out into a barren wasteland for 10,000 Days.

the studio with helium and playing his self-designed Mandala electronic pads for sampled effects. Carey's recent tabla studies have also affected the band's music, as has his distinct lack of individual practice. And by playing a set of Designer Series Sonor drums that were built to his exact specifications, Carey was able to express his drumming soul as never before. But certain nagging questions remain. Will Carey ever record a solo record, cut his own instructional DVD, or tour as a solo/clinic artist? Honest to a fault, he will answer your questions. But whatever you do. don't ask Danny about "those monkey show clinics." He just might tell you the truth, or cast you out into a barren wasteland for 10,000 Days.

The rhythms on the new album arc very circular, as if at times Tool meant to create trance music.

Especially on the longest song, "Wings for Marie." That's about 17 minutes long, and we definitely went for a cyclical thing. Maybe my tabla training is rubbing off on the rest of the band. The second part of that suite is called "10,000 Days." They were written as one piece.

A couple of tracks sound like you're using sticks on tablas, very electronic-sounding.

They were samples of tablas played with fingers. There's one song where I

play real tabla with my hands, but most of the time, because of the difficulty

of switching back and forth between instruments and just keeping up with

the band volume, it's impractical to play real tablas. So I use samples. I play

them on my new Mandala pads with sticks.

Tell me about your new pads.

I've used a prototype of these pads most of the time in my set. They've replaced my old Simmons SDX pads. I'm running a program called Battery from Native Instruments that manages all my samples. I run that through an Apple Mac G5. A Firewire audio device runs out of that into the mains

of my mixer. For a drummer, it's the best MIDI interface you can have. "It's zone intelligent, meaning it knows exactly where the stick hits the pad, besides just reading volume, which is something most other pads don't. have. I can apply that to any parameter I want. I can make it pan left and right, open a filter, increase volume, or pitch bend, just by hitting the pad on different parts of the surface.

It sounds like you're playing Cubans on the record.

Those are the Mandala pads with Octoban samples. I sampled a set of the old, clear Cubans like Billy Cobham used to play. I also loved Stewart Copeland's Octoban work. That was prime time for me.

|

|

Is your setup generally the same as on your website, DannyCarey.org?

Is your setup generally the same as on your website, DannyCarey.org?

I still use the Wave drum, but now I have the Mandala pads. And I have a great new Designer Series kit from Sonor. I designed the shells out of specific woods and thicknesses, and it turned out amazing. The wood is from the South American rainforest. It's called Aniba ayabuascus rosaeodora. It is a drag, though, because there was this bird, the diving petrel, that nested in this tree and it was one of the last of those trees in existence. So this bird may become extinct because I had to have that wood. Well, it's worth it as long as everyone gets to hear me play these drums.

Too! is a loud band. Do you record fallout in the studio?

Oh, yeah. It's cranking Les Pauls played through Marshall stacks. It's not so important to record that way. But it is important to play at that volume when we're all in the same room writing together. My drum kit is really loud, too. I've always felt that thick-shelled drums, like the kind I'm using, sound best when you hit them hard. Then you can hear a little bit of the wood. You're not just hearing the plastic head vibrate.

You don't believe a thinner shell resonates more?

In the low end it docs. But that's why I designed my Sonor kit the way I did. My smaller toms have very thick shells. On my 8" torn, the shell is over an inch thick. Then as the drums get larger, from

10" to 14" and 16", the shells get thinner. That way the bigger drums reverberate and resonate the low end better, but the small drums still cut through.

How thick are the bass drum shells?

The bass drum thickness is around 3/8"-not real thick, but enough to generate a heavy fundamental. The kick drums function in a different way, the toms arc very critical. You really want a strong fundamental on the bass frequency.

Why do you continue to use two bass drums instead of a double pedal?

I think two bass drums sound better. I like the reverberation of a drum being hit when it has a little more time to recover. When you use a double pedal, there are times when you're overplaying the head. I think it just sounds rounder and fuller when you use two lack drums as opposed to one.

As fast as some drummers play, they're definitely choking the head.

Oh, definitely. And you're not going to get the depth of tone that you would out of two kick drums. It's just physically impossible.

Why do you generally play with the snares off?

I do that about half the time. I just realty like the sound with the snares turned off. It's not quite so intrusive on the high end. I do like to go back and forth, for instance, turning the snares off for a verse and turning them on for a chorus.

How do you tune such a unique set of drums?

The bottom head is usually higher. On the toms, the difference is maybe a fifth or fourth higher. On the floor toms, it's not quite as much, maybe a third.

Are your top heads generally loose or tight?

Fairly tight. I'm going for definite pitches, and I like the drums to sing. I love sustain. I usually try to tune them to the triad of the song we're recording. Ninety percent of Tool songs are in D,

so I tune the toms to D, F, and A I try to hit the pitches of the triad because, when they're in tune with the song, they sound bigger and fuller. If they're out of pitch, the sound of the drums doesn't seem to sing as much with the band.

I lave you worked on your drum set play-ing a lot since Lateralus?

I find that I become insensitive to songs if I start practicing exercises too much. I've put a lot more time and emphasis on playing and interpreting music and being sensitive to the other three members of the band. I'm trying to do justice to those magical moments that happen when we're in the room together. That's the most important thing to me. So I hate to say it, but I hardly practice at all outside of practicing with the band. It's worked for mc, though. I'm more a part of the music when I approach it that way.

How do you stay open to those "magical moments”?

Everyone has their own sort of meditation, for lack of a better word, that they do. It's not about thinking as much as it is about thinking, just trying to empty your cup so you have somewhere to go. The most important thing to not bring any mental baggage to the table when we're practicing composing. Let the music speak for itself. It's not so much about you; it's about the music and the energy that's happening in the band.

|

TOMAS HAAKE

Wereyou a fan of Tool before touring with them?

It was a funny thing, because I had never realty gotten into them, but then I picked up Lateralus just for fun, pretty much a month or two previous to us touring with them the first time. And I just got into it heavily. Then I bought some of the older stuff as well, and now AEnima is one of my favorite albums.

What was it like opening for Tool?

We had a blast. We immediately had the feeling that they really wanted us on that tour. And all their people were kind of working for us, too, without us paying for them. [Laughs]

What influence have Tool had on Meshuggah?

We try deliberately not to really have too many influences as far as our music, but I think for all of

us in the band, just being out with them and seeing them live, it's impossible for Tool not to have an impact of some kind.

MIKE PATTON

When did you first meet the guys in Tool?

We were all members of the Kansas fen club and met at a Kansas Krazies convention in Topeka in 1978. We were hanging out in the hotel bar at the Holiday Inn and Adam started playing a reggae version of "Carry On Wayward Son" on the piano. Justin and Danny-picked up the bar band's instruments and joined in and Maynard grabbed the mic and let it rip dressed in this Kansas state trooper uniform. I was in awe! I introduced myself and told them about my band Mr. Bungle; they said that they were in a band called

Theremin Toolbelt. I told them that they were great but that the band name was a little goofy. To be taken serious they should pick a serious-sounding name like Hammer or Wrench.

What has it been like touring with Tool?

Honestly, it has been great! Tool always pays us fairly and treats us very well. I admire that they do whatever they want; they don't take orders from record labels or "industry types." My hat is off to them.

How have Tool's fans responded to your bands?

Weeeeeeeeell. During the Fantomas run, I collected a lot of spare change from the stage after each show. I can't complain though - if I paid $60 to see my favorite band and a bunch of noisy weirdos took the stage, I'd be violent, too!

What influence, if any, have Tool had on you and your own work?

They give me hope that not all huge bands are

pompous, clueless, drug-addled morons. That, and I steal lots of fashion ideas from Maynard's stage wear.

BUZZ OSBORNE

When did you first meet the guys in Tool?

It was in the early '90s when they opened for us at the I folk/wood Palladium at a show with Gwar. Adam now says we were "mean" to them, but I know that's bullshit because I'm never mean to anyone. I don't remember much about them, but about two seconds later they were all over MTV I'm surprised they ever talked to us again. Later on, in about '97, we did an arena tour opening for them, and then in '98 they asked us to do the horrid Ozzfest tour and I became better friends with them. Adam is one of my dearest friends.

How have Tool's fens responded to your bands?

It varies from bad to worse. Some of it was OK, but by and large arena-level audiences are total idiots and Tool's crowd is no different. I remember once a Tool fen insisted on stopping me in the hallway after our set to explain in detail why we sucked. I listened for about 30 seconds and then I showed a security guard my all-access pass and told him I saw the guy pull his pants down in front of a chick coming out of the girls' can and the kid got tossed out on his ass before Tool even played! Ha!

What influence have Tool had on you?

I've worked a lot with Adam and I dig it a whole lot. He understands my strange way of writing songs and lie's not afraid of noise. He has a really great guitar tone, which I would love to steal.

What do you think makes Tool so unique?

Smoke and mirrors.

|

Дата добавления: 2015-10-23; просмотров: 90 | Нарушение авторских прав

| <== предыдущая страница | | | следующая страница ==> |

| WHEN THIS WRITER FIRST INTERVIEWED 6 страница | | | Однопродуктовая статическая модель без дефицита |