Читайте также:

|

CAREY: I know we all were doing a lot of psychedelics during that era — not that we hadn't for our whole lives. But there's no doubt that it

lays a precedent and releases a more creative part of people's minds. It's scientifically proven. And I think we were able to share more personal things with each other and to dig a little deeper and expose those parts of our personalities or our psyches in a bolder and more revealing way. And that's where the music naturally went.

JONES: Musically, it was critical just to understand that we weren't really getting what we wanted with Sylvia Masse)'. She's a good engineer and a very nice person, but I'd never work with her again. We wanted to find someone who was more than an engineer. And Danny and I had heard the David Sylvian/ Robert Fripp record [1993's The First Day], which David Bottrill had done. It was just amazing. You could hear every instrument and it was very dynamic and we thought it really applied to what we were doing. So we called David up and he was into it.

KEENAN: Another difference between Undertow and AEnima is I had a son. When that happens, your friends run out the door to go dive off a cliff head-first and you just lands go, "You know, I'm gonna hang back. I've got some responsibilities here." It changes you on some level in a positive way. The catharsis I was looking for on the first couple of records came in the form of this child, which helped me direct all that struggle and the stress and that emotional turbulence that I was experiencing for so long, and calm it down and give it more focus. The other guys don't have that. It's hard to say if that's a positive or negative. I think it just keeps us where we are and it's a very good thing there's still that counterfire and counterbalance and juxtaposition, but I sure would love to sec them get to that space in their life.

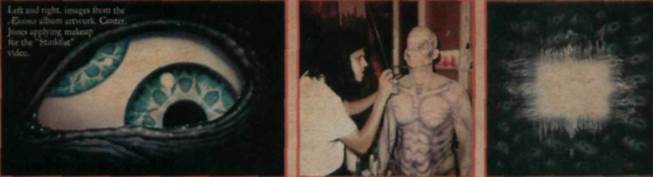

JONES: When it comes to our artwork, I'm always thinking, Let's do something that's never been done before, or How far can we push something? I found this little indie CD that had a lenticular cover on it, but it moved. It had two frames of back-and-forth animation, and I just freaked out. Our manager found the little company that put it out, so we contacted them.

|

|

and told them we were thinking about doing, possibly, a million copies. I think we were the first commercial band to do that. Artistically, that's the kind of thing that realty excites roc.

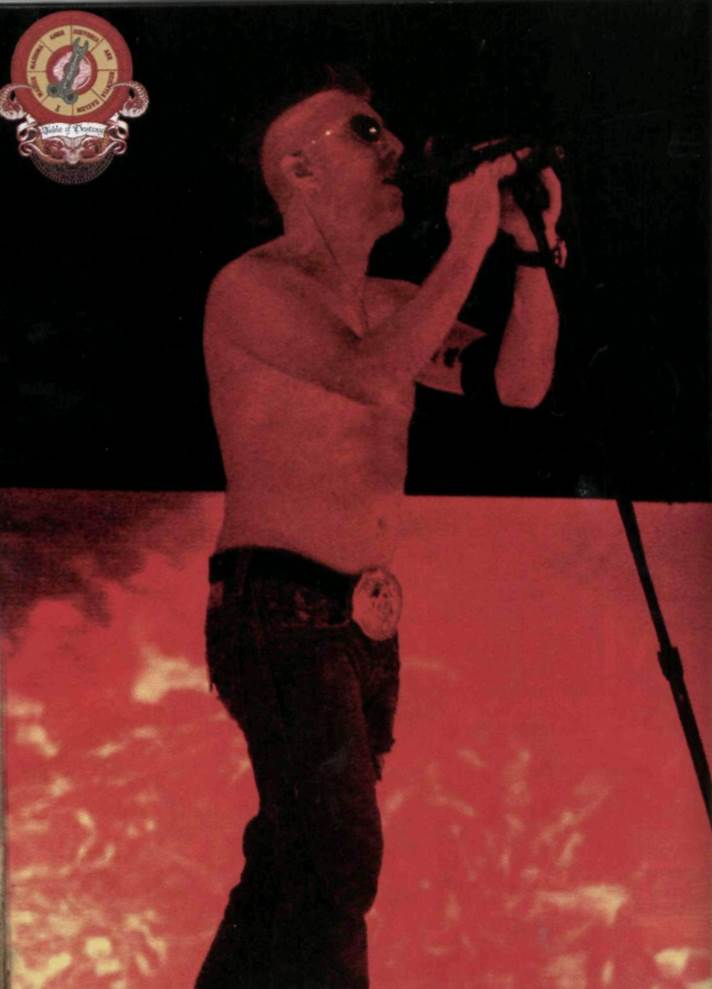

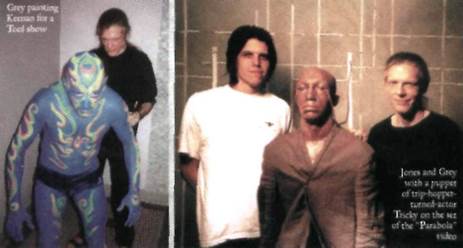

KEENAN: I painted myself blue for about three years. It was a lot of work, but it was something to take you outside of yourself. That's part of what AEnima was to me — just to put on some of the craziest, eyesore costumes I've ever worn in my life, and kind of free myself up. I'm kind of a reserved, quiet person, and it's very difficult for me to open up in general. And to open up onstage in front of that many people, you kind of need a costume. Being painted up like that helped, but eventually you're onstage trying to do your thing and your pores arc clogged with paint. It just takes its toll. I'll still go through my closet and find pieces of clothes or shoes that are just covered in blue paint. But I think we toured a little too much overall for that record, and I started to realize how I've got this responsibility that the other guys don't have. You've got these two little flaps of skin in your throat that are very volatile. And there's things you just can't do, otherwise they just don't work and the sounds don't come out. You can't just buy another piece of equipment to replace it. And as time goes on and you get a little older, these weird tensions start to come out because of that. You're like the pregnant girl who can't go into the smoky pub. Everyone else wants to go in, and you're like, "No, I really can't," and they go, "Oh, right, you can't go in there. OK, well we'll find someplace that's not as fun so the pregnant woman can hang out with us."

|

|

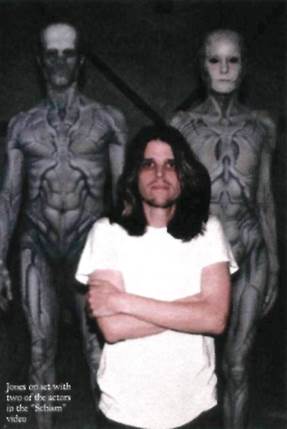

INSTEAD OF TAKING A LENGTHY BREAK AFTER TOURING FOR AENIMA,

Tool headed right back into the studio, where the musicians quickly got on each other's nerves. At the same time they became involved in frustrating legal battles with their former label and manager. The stress was too much and, following months of disharmony, Keenan left to record with his new project, A Perfect Circle. He eventually returned and wrote the vocals for Lateralus, some of which documented the turbulence, like these words from "Schism": "No fault, none to blame. It doesn't mean I don't desire to/Point the finger, blame the other/Watch the temple topple over." Lateralus probably should have been a train wreck, but somehow it wasn't. The internal tensions not only failed to damage the musical chemistry but actually seemed to strengthen the songs. Evocative, progressive, and imagistic, Lateralus is a moving palette of colors and emotions infused with lava-lamp guitars, dizzying rhythms, exotic tribal beats, and an ever-present sense of dread that keeps the music heavy even in the absence of obviously metallic structures. And while much of the record is inchoate and trippy, tracks like "Schism," "Parabola," and "Ticks & Leeches" feature meaty riffs that prove that when they want to, Tool can still rock as hard as ever.

|

|

KEENAN: The other guys were plodding along, trying to really take their time, and for me it was very frustrating. I understand that the

process they have to go through involves taking every avenue possible and going down it to see if they get

anywhere, and coming back and then

starting over at another avenue. But it's a very tedious and long process that doesn't really lend itself to telling a story. I kind of need some of the foundation there, because if the foundation keeps changing,

the story's gonna keep changing. I realized that if I had to go through ли entire two- or three-year process of trying to write like that, I was going to go out of my mind. I needed to get things on paper and express them \ and get them on tape way sooner than that. So that's when I went and worked with my roommate, Billy Howerdel, to do A Perfect Circle. I had no idea that it was gonna blow up as big as it did. I thought we were just going to be messing around J town, doing some club gigs and

|

|

|

having fun with it. And then right underneath our feet, it just kind

of took off. I didn't really kick and scream. I went along with it willingly.

JONES: The communication was so bad at that point. I'm one of those guys that goes, "What's happening?" and "Why are you upset?" And other people arc going, "I'm not upset." But they really are. We were at that height where we were in a successful band and yet we were all kind of growing apart almost because of it, and people aren't communicating and other people's feelings are

getting hurt. The biggest problem I had was that I never knew what was really going on. And then Maynard left, and while Maynard was making plans with A Perfect Circle, we were making plans as well. And I was sitting there thinking, Well, OK, when are you gonna be done with this so we can do our thing?

|

CHANCELLOR. I definitely felt the band was in jeopardy at that point, but I've often felt that And the way we always get through it is to not push it and not expect

things to suddenly be OK. We

let them play themselves out and

eventually deal with

the problems and see

if we can get further.

And sometimes

that takes a bunch of time. And it takes leaving each other alone for months and then coming back. It takes fighting with each other. It's never quite come to fistfights, but it's been really very explosive. But every time that's happened, we've gotten a lot further and that's really how we've managed to carry on. If you try to ignore that stuff, then there's no hope in going on at all.

KEENAN: After I finished with A Perfect Circle, coming back to the Tool camp caused a lot of tension. "Where were you? You're off with your mistress again"-that kind of thing. We've since navigated that, but of course initially it was always a sore spot and it made getting into Lateralus a bit of a chore. But it's really the friction, that juxtaposition of forces that makes good art. Having said that, if there's any criticism I have of us it's that we tend to forget to step out of that character and go, "Oh, yeah, this is all fun. It's supposed to be art. It's supposed to be a release. It's not supposed to give us ulcers."

CHANCELLOR. For me, the song "Lateralus" was the turning point. I wrote a bar of nine, a bar of eight, and a bar of seven, and we originally called the song "987." I saw it as something that kept getting shorter and shorter and, like a spiral, it kind of folds in on itself. And Maynard had no idea what I was thinking when he

|

|

went to track the vocals. But as the song's folding and changing, he's singing about the idea of a spiral and how you're basically trying to achieve something that's never been achieved and you have to keep reaching for something that you don't understand. I thought that was an incredible synchronicity. Then a friend said, "Justin, do you realize that 987 is the 16th number of the Fibonacci sequence? It's the mathematical equation for a spiral." I'm not the most spiritual person, but all that stuff was almost like a reward for all our efforts, and I felt like it got us back on track.

KEENAN: For the lyrics on Lateralus, I wanted to address the same kind of stuff as AEnima. I wanted to explore that sense of release, kind of combining archetypes with where we were in our lives at that point. On the previous album, we had gone through that whole transformation, what some refer to as the "Saturn return"-your 28th or 29th year, when you're given the opportunity to transform from whatever your hangups were before and to let the light of knowledge and experience lighten your load, so to speak, and let go of old patterns and

embrace a new life. It's kind of the story of Jonah and the belly of the whale. You kind of sink or swim at that point. And a lot of people don't make it. Hendrix, Janis Joplin, and Kurt Cobain didn't quite make it past their Saturn return. For me. starting to recognize those patterns, it was very important to start constructing songs that chronicled that process, hoping that my gift back would be to share that path and hope that I could help somebody get past that spot. And the first step in that is just being aware of it.

CAREY: To see that record get accepted and go to No. I on the charts was such a relief! I remember that even when we had finished it we were like, "God, this is really fucking crazy. These songs arc even longer than the ones on AEnima and some of them are weirder and more psychedelic," We thought, Oh man, arc people gonna even want to hear this? At that point, it had been five years since AEnima and it felt like people's attention spans had gotten even shorter. There was all this DJ shit going on and no one was even listening to live bands in a lot of clubs. I remember Nine Inch Nails put out The Fragile, which I thought was pure genius, and it hardly sold any copies. We were like, "Goddamn, are we gonna get dissed, too?"

|

|

|

|

EXPANDING UPON THE

formula (or lack there of) of Lateralus, 10,000Days is filled With bizarre time signatures, unconventional riff structures, and open-ended phrasing, but some of the tension has been replaced by melancholy reflection. The album title refers to the amount of time Keenan's mother suffered from stroke-related paralysis before she died, and on "Wings for Marie (Part 1)" and "10,000 Days (Wings Part 2)" the singer drops his guard and candidly addresses their relationship ("It was you who prayed for me/So what have I done to be a son to an angel?"). But while 10,000 Days showcases some of Tool's most confessional, contemplative moments, it also contains some killer rock-outs. On "Vicarious," powerhouse drum fills muscle through chunky, off-kilter guitars and harsh, haunting vocals ("1 need to watch things die/From a good safe distance"). "The Pot" melds a funky bass line to a jagged, staggered riff and includes the infectious chant-along "You must have been high." And "Jambi" is propelled by Indian percussion and chugging axwork, peaking with a dizzying Talk Box guitar solo. Regardless of whether Tool are zoning out

or rifling away, 10,000 Days exposes a band functioning at peak capacity and unafraid of risking everything for their art.

KEENAN: You can tell which tracks the other guys were working on while I was touring with A Perfect Circle because they kind of meander off and go crazy and there's all these complicated turnarounds and loops. It requires some form of psilocybin to enjoy - which is great. I love having something that I get to enjoy because I wasn't there in the kitchen helping cook it. And I can add my spice to it later and take it to some other level. It's a good thing I was away, though, because those guys definitely needed to chase their tails again and go down blind alleys awhile. Then, once we all got back together, having done all those experiments, that's where it really flows. And that's where we can do the ones that are just fun to play, like "The Pot" and "Jambi." But it takes that internal/external digestion to get there.

CAREY: We had lots of ideas from all the jams for Lateralus, so we had a few good starting points to go from. And we thought, Oh yeah, this is gonna be way easier for us than the last one. And in a lot of ways, it wasn't. We had all just become bigger assholes and everyone's

|

|

|

|

idiosynerasies had become even more grinding on each other. But we arc also smarter and know that those are just our personalities, and at the same time we've become more accepting of giving each other space in order to deal with them — not that it makes you any happier about it when it goes down. I couldn't say doing 10,000 Days was any easier. And I think about the next record and go, God, it'll be easy, but once we start in on it, it'll probably be even harder than the last one. But it'll be better, too.

CHANCELLOR: The first song we worked on was "Vicarious," which we made quite difficult for ourselves. It was like we were never prepared to finish writing it, and it took a good couple of months to really nail down and get back to the core of where we began. We were doing other stuff at the same time, but we kept coming back to it because it felt like the key for getting into the album. We actually only find special things by really searching. We don't ever write stuff individually and say, "OK, this is gonna be the song." We bring in ideas in their rawest form and bounce them around to find the thing that is bigger than I any individual's idea.

JONES: Whenever you finally find yourself

on a roll and you finish up a record, you go,

OK, I wish next time we could just pick up

where we left off at this exact moment. But

if you did that, you'd just be redoing the same

thing. That's what blows my mind about

certain bands that put a record out every year.

I always go, This sounds like a garage band

doing covers of your last record. You know?

You don't grow. I just feel like you gotta let

something breathe. So that's why taking a year

off between records is good, because when we

come back we appreciate what we're doing more and we look at it in a different light.

KEENAN: I was kind of hoping on this album to get back to some of the energy we had expressed on some of the early records, where

we had four-on-the-floor Sabbath-like grooves that were fun to play. On some of the later records, it was very difficult to get a groove going because everything was so complex and choppy and like running up an uneven set of stairs with a blindfold and a wooden leg. I wanted to do some of that because I really enjoy the challenge of a puzzle, putting lyrics to those complex pieces, but I really was looking forward to trying to get back to something simple so I could just run down that set of stairs with my eyes closed and know that I'm gonna land on my feet. That happened to some extent on 10,000 Days, but as soon as I walked in, there was the tension in the studio trying to get everyone on the same page without making someone compromise what they're doing to go there.

JONES: Another thing that was slowing us down was some more legal problems. Once again, we were being sued for this and that, and it seems like every time we've had legal problems, most of them have been some kind of knee-jerk, "Pay us off quick so we don't cause a lot of trouble" kind of thing. I really hate that in our legal system, how the poorest person can come up to the richest person and make some insane claim. We just get the craziest people who go, "Hey, I wrote your record and you stole it from me. And I'm Jesus and you're the Devil."

KEENAN: I think probably the stupidest thing I could have done on 10,000 Days was put myself out there as much as I did with the tracks "Wings for Marie (Part 1)" and "10.000 Days (Wings Part 2)." I'll never make that mistake again. It just took too much out of me emotionally, mentally, and physically. It's just too difficult in what I would consider a hostile environment. It's not a very nurturing setting, a Tool concert. There's lots of people there that get it, but there's definitely a percentage who don't and it's a very, very, very difficult place to try to express those kinds of feelings. So, having put yourself out there in that way with songs like "Prison Sex" and "Wings," I don't want

|

|

|

to do that anymore. All those songs were exploited and misconstrued. People were flippant and dismissive. And technically, "Wings" is very difficult to pull oft", so if any one of us is off, it falls apart and makes that thing tragic, and that's not a good song for me to have fall apart.

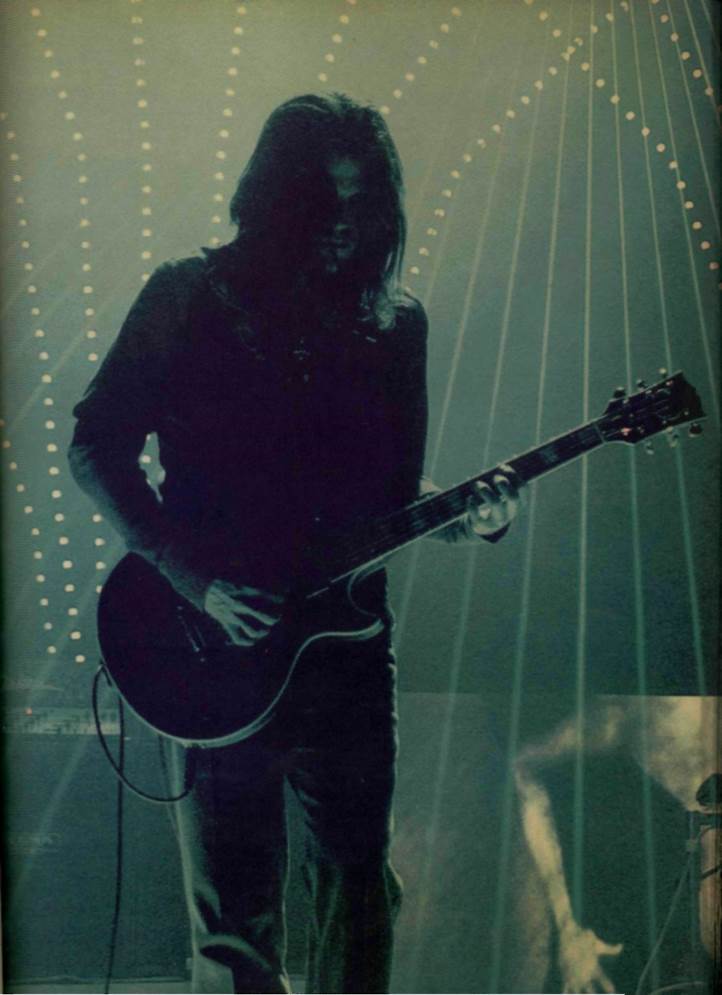

CHANCELLOR: Playing "10,000 Days" in concert was

very challenging but infinitely rewarding. It's much

more sensitive and emotional than our other songs, and

it requires pacing yourself and also being very vulnerable.

So, to play that in a big, massive arena with lasers going,

when that one came oft, you rise out of your body and

actually start to sec everything from the outside and be

able to enjoy it because it's all working and playing out

so naturally. For me that was as good as it's gotten in this band.

CAREY: David Bottrill was great on AEnima and Lateralus, but we knew we wanted to use someone different to record 10.000 Days because we never want to make the same record twice. David was a drum-heavy person and Adam wanted to use a guitar-oriented guy more. I was a little worried about it because I loved the records Joe Barresi had done with the Melvins and Jesus Lizard, but I never really liked the drum sounds. And I had to work with him at it, but I think I got the best drum sound I've ever gotten because he's got great cars. But he's definitely a guitar guy and I had to fight tooth and nail to be heard. I learned a lot by going through that.

JONES: To release some of the stress in the studio, Maynard and I would shoot guns. Maynard lives out in Arizona and he can get all the cool guns that you can't get in California because some kid shot himself and ruined it for everyone. So Maynard brought his guns in and we did some target practice on these to-do lists that we had for every song. He got a human target like police use to shoot at, and he put these sheets on different places of the target. So it was like, if you shoot at the head, the bass is done, and if you hit the chest, the vocals are done, and if you get the

|

shoulder, the guitars arc done. We did the record at Grand Master, where we recorded Undertow, which has such a cool vibe. Some places you record can be so strict sometimes, but Grand Master was just like, "Hey, this is your place and you can do what the fuck you want. Just don't kill anybody."

CAREY: We spent a little longer

on 10,000 Days because we

knew time wasn't even a factor.

We spent about a year writing,

but the recording went pretty smoothly. I did my drums in seven days and then Justin did the bass parts in, maybe, three weeks. And Adam took close to two months doing all the guitar layers. He just used a lot of different amplifiers and developed his sound way beyond what I'd ever heard him do before.

JONES: One thing I remember is that right before we recorded the album, the company that makes the big reel-to-reel analog tape went under, so we couldn't find tape to record on. That was a problem because we don't like recording straight to digital. We record to tape to get an analog recording, then we bounce that digitally because it will capture the analog sound. So we had Joe Barresi running all over town buying all the tape he could find. And we actually have extra tape that we didn't use sitting in an air-temperature-controlled vault so we can use it next time.

CAREY: When we were done recording, we mixed at Bay Seven in North Hollywood, and while we were there, we did some overdubs with a magical microphone that Adolf Hitler used. It had the little flying eagle swastika insignia on it. We were like, "Oh, you've gotta be kidding, dude." It turned out that the owner had just driven all over the country and found a whole box full of these beautiful old Telefunken microphones from the 1940s in some guy's garage and brought them back. And we just went, "Oh, God, we've gotta use that, man. That's got some voodoo in it." Maybe it added that little touch of evil that the record needed. Without any evil, there's no good.

|

|

|

|

| IT'S A TESTAMENT TO ARTIST ALEX GREY'S dedication to his friends in Tool that he was willing to talk to Revolver about his collaborations with the band — on the day after his dad's funeral. Our schedule for producing this issue was extremely tight, and since Grey was leaving for the World Psychedelic Forum in Switzerland that evening, it was really the only opportunity for us to converse. "No, no, I'm glad we could talk," the soft-spoken Grey says sincerely when we express our condolences and apologize for the poor timing. "We had a really beautiful ceremony, and you know," he continues philosophically, "everyone's time comes.' The death of a loved one is always hard, but if anyone is York City. While a visit to the Chapel prepared to cope with such an ordeal, it might be Grey. He may shed light on some of the questions |

has been tackling the issue of mortality and the question of the great beyond head-on since he was a kid growing up in Columbus, Ohio, collecting insects and dead animals and burying them in his back yard. Then, from 1975 to 1980 he worked at Harvard Medical School preparing cadavers for dissection, an experience that clearly informs the anatomically intense paintings for which he is famous. While much of his earlier artwork had a dark, transgressive edge to it - in a 1975 performance piece, Life, Death, and God, for instance, he tied one end of a rope around the ankle of a corpse, the other end around his own ankle, and hung himself and the cadaver upside-down on the wall with a drawing of a crucifix posted in between-his latter-day work is infused with hope, compassion, and spirituality even if it is full of skeletons and body parts, images that most folks tend to find "morbid." This evolution toward a more optimistic outlook to some degree mirrors Tool's own trajectory from angst-filled '90s metallers to mystical new-millennial prog rockers, America's biggest self-proclaimed "psychedelic" band-in counterpoint to Grey, "America's foremost psychedelic artist," according to High Times magazine. So it seems almost inevitable that the artist's and the band's arcs should intersect, as the}' have frequently since 1999, when Grey met guitarist Adam Jones and went on to create the stunning artwork for Tool's 2001 album. Lateralus. Having also lent his vision to their follow-up, 10,000 Days, as well as their music videos, stage sets, and T-shirts, Grey and his transcendental art have become inextrieably connected in the minds of many to Tool, leading numerous fans of the band to make a pilgrimage of sorts to the Chapel of Sacred Mirrors, the gallery space and "sanctuary for contemplation and creative spiritual renewal" that Grey and his wife, Allyson, run in the Chelsea neighborhood of New

Дата добавления: 2015-10-23; просмотров: 79 | Нарушение авторских прав

| <== предыдущая страница | | | следующая страница ==> |

| WHEN THIS WRITER FIRST INTERVIEWED 1 страница | | | WHEN THIS WRITER FIRST INTERVIEWED 3 страница |