Читайте также:

|

With only one album's worth of material, APC construct newer compositions out of existing lyrics and songs, weaving them together into a sort of live rock remix. Songs flow one into the next, forming a flawlessly executed suite of glamour, tension, and fetching misery. The band close with a stellar version of David Bowie's post-glam classic "Ashes to Ashes."

Tool and APC rarely play encores. "1 don't jerk off the crowd," Keenan has said. Tonight his only words of closing are, "Well, there you have it." No giant toilet, no cage dancers, no inflatable pigs. And somehow, nobody seems to have the feeling they've been cheated.

CLEARLY, KEENAN HAS GOT

this whole art-rock thing perfectly wired

|

|

He recognizes the plight of bands hoping to freshen cock-rock postures with post-Cobain angst. But he suggests looking a bit further back for inspiration. "1 think bands like Queen and Judas Priest ended up shining out of the crowd back then," he says. "1 think the vulnerability and emotional aspect in their heavy music was recognizable because it was genuine. 'Cause you figure, Rob Halford and Freddie Mercury being gay, and they can't say it out loud, that's a lot of genuine frustration, genuine passion." Do not hold your breath waiting for another current rock singer to champion the transcendent value of a gay frontman.

Keenan's idea of frustration and passion were formed growing up with a secret in a small town. The son of two Midwestern high school teachers, he was a varsity wrestler, a track athlete, and a deeply closeted Joni Mitchell fan. "You

episodes. As with his time in the pet industry, these experiences arc hardly lost on his current occupation.

"Maynard's just a realty funny person," says Carey, an opinion borne out by the bone-dry humor running through the records themselves: On AEnima's "Die Eier von Satan," what sounds like a Nuremburg rally excerpt is actually a cookie recipe read in German through a megaphone. "Message to Harry Manback" sets an obscene, semi-coherent death threat from a friend's ousted roommate to a moody, Nine Inch Nails-esque piano nocturne. More recently, Tool's website shared with eager fans supposed new song titles like "Encephalitis," "Coeliacus," "Pain Canal." and "Lactation," goofs on the death-metal aesthetic and Tool's own reputation.

If as Goethe wrote, "men show their character in nothing more clearly than by what they think laughable," Keenan is in some rare company. But if we also judge a man by the company he keeps, he seems just as unusual. Keenan's friends include Trent Reznor and members of Rage, Melvins, and Deftones, all of whom are also collaborators (Reznor and Keenan are leading the upcoming black-clad, super-secretive supergroup Tapeworm).

"Maynard's approach to music is out in left field in comparison with other musicians," says Deftones's Chino Moreno. "I'm

teous indignation is somehow very Tool.

And yet, the last time a long, torturous, highly anticipated album from a tormented rock hero came out, it didn't exactly shoot up the charts — although critics and Tool agree that Nine Inch Nails' The Fragile was a brilliant work. The road now seems to be even rockier for a supposed metal band that wants to make art.

For their part, Tool don't seem too worried. There are few things Keenan has an abiding faith in, but the fans seem to be one of them. "Tool fans aren't masculine to the point of grunt-rock or whatever, with that kind of herd mentality," Keenan says. "Maybe I'm completely kidding myself and overestimating our audience, but I feel like there's a definite percentage more thinkers"-the assumption being that said thinkers will support thoughtful music.

|

couldn't realty bust out Joni Mitchell in high school," he recalls. "You had to play the Knack, AC/DC, and the Cars."

After high school, Maynard did a fairly strange thing for a future metal warrior: He joined the Army. He calls the decision an exercise in contrarianism. "It was basically, Let me do the most ridiculous, illogical thing I can think of," he says. "And after that, if it's not right, I'll know it's not right."

And when did he feel it wasn't right?

"As soon as the bus pulled out of the parking lot. Realizing I just...fucked up."

Post-discharge, Keenan soon succumbed to the same force that lures so many dreamy-eyed young people to Los Angeles: the pet industry. Partly as a result of his gig at a chain store called Petland, he is currently the proud owner of four hairless cats. "Emotionally, they're more like dogs," he says. "They're not so aloof."

Keenan also gravitated to the underground comedy scene, where he performed in after-hours clubs, making friends with up-and-coming comics like David Cross and Bob Odenkirk, who later cast him in a couple of Air. Show

pretty sure he knows all that, and it's probably why he's such a smartass little fucker." Keenan is also friends with Judas Priest's Halford, Megadeth's Dave Mustaine (with whom he's reported to share a vacation house), and, most surprising, Tori Amos, who shares with Keenan a Christian upbringing and a lasting fascination with religion.

"He really is this beautiful guy," she says. "And he believes that you can't separate yourself from what you create. I think we both believe that whatever you put out there, the phrase 'Oh, I'm just kidding' is fuckin' weak. He does not negotiate with his beliefs, and if he's a friend, he's a real friend. He just has this deep spiritual currency."

THE SUN IS SETTING AS Keenan finishes his stroll through CityWalk, the scenery recalling AEnima's description of LA. as "one great big festering neon distraction." A shrill alarm comes wailing out of a storefront. "You're not allowed to have fun here," Keenan muses. "Some fun was probably just detected."

Keenan and his bandmates have spent 10 years negotiating the crassest commercial pressures and have a survivor's humor about it. In the AEnima song "Hooker With a Penis," the singer is confronted by a young fan in "Vans, 501s, and a dope Beastie tee" who, between sips of Coke, calls him a sellout. His response is the mea culpa "I sold out long before you ever heard my name.../So shut up and/Buy my new record/Send more money/ Fuck you, buddy." The mix of sarcasm, self-loathing, and righ-

With luck, they will. One of Tool's central accomplishments might be taking this musical language of heroic Sturm und Drang. of wizards, damnation, hammers, and anvils — and, more recently, caricaturized adolescent pain—and populating it with more real discussions of life's extreme moments and thoughts. Despite the pressures of a homogenized marketplace and the lure of other projects, it's likely that this band has spent too many years tending to this unique creative outlet to just give up.

Walking toward the "Jurassic Parking" garage, we find ourselves in the cool glow of the gigantic, neon Fender guitar that looms over CityWalk's own Hard Rock Cafe. The mosque-shaped building provides a fitting image for the profound aspirituality the rock industry in 2001.

When I ask how Tool plan to get that industry to embrace a record high-minded as Lateralus, Keenan answers concisely, in a manner befitting someone with deep spiritual currency.

He chuckles and says simply, "Pray."

|

|

|

ON A COLD AND RAINY BELGIAN

morning late last year, I was nursing a particularly nasty hangover when one of my fellow patrons in the hotel restaurant struck up a conversation.

"You are a music journalist, yes?" asked a paunchy, balding, grinning German gentleman in heavily accented English. "Do you know Maynard from Tool?"

I explained that I knew Maynard James Keenan's work, but not the man himself". "Why do you ask?" I wondered.

"Because he is the same age as me!" answered the German, still grinning.

Whenever Tool come up in conversation, things inevitably get a little bit strange. Ever since emerging from the smog-choked Los Angeles basin with 1992's Opiate EP, the multiplatinum art-metal quartet has radiated a distinct aura of "otherness." The band - whose lineup consists of vocalist Keenan, guitarist Adam Jones, bassist Justin Chancellor, and drummer Danny Carey-has consistently kept the mainstream at arm's length while cultivating a deeply mysterious image. In the process, they've managed to acquire one of the most diverse and obsessive fan bases in rock music. You probably couldn't pick a Tool devotee out of a lineup, yet they always seem to pop up at random moments, wanting to discuss some obscure Tool-related factoid (as did my German friend), or an intensely cogitated theory about a certain Tool song, video, or piece of album artwork.

Like one of those gigantic spaceships in that '90s sci-fi flick Independence Day, Tool have spent nearly 15 years hovering impressively and impenetrably over the music world, while those of us on the ground below debate the "meaning" behind the mysterious craft. Are these guys using music, as they themselves have claimed, to tap into a higher spiritual consciousness? Or is this some kind of elaborate put-on, with lyrics and images offering indecipherable "clues" that ultimately lead you on a journey to

nowhere? Or are Tool simply the logical contemporary extension of the '70s progressive-rock movement, in all its pretentious, technically proficient glory? With the arrival of every new Tool release, the debate is reignited.

10,000Days (Volcano/ZLG), the band's latest album, will surely inspire more of the same. The first Tool release since 2002's acclaimed Lateralus, the CD is filled with epic songs (the 11-track disc clocks in at nearly 80 minutes) based on hypnotically complex rifts and anguished vocals, and cloaked in typically oblique artwork. Produced. by the band and engineered and mixed by Joe Barresi (Queens of the Stone Age, Bad Religion, Judas Priest), 10,000 Days isn't a great departure from what the group has done in the past, though it may be the densest- and heaviest-sounding Tool record yet. On tracks like "Jambi," "Lipan Conjuring," and "Intension," the distinction between guitars, bass, drums, and vocals is almost completely obliterated at times by the sheer density of sound.

"With us, it's a ball of concentrated music," says Jones. "We all kind of allow each other to play each other's parts," adds Chancellor. "It's never like, 'You're the guitarist, you're the drummer, I'm the bassist.' Even Dan plays melodies sometimes, you know? The idea is that you can do anything in this band."

Though their intertwined instrumental melodies, telepathic rhythmic shifts, and sprawling song arrangements often sound like they could be the work of Hell's own jam band, the fact is that Tool's songs arc meticulously mapped out before the bandmates even enter the recording studio - which is one of the reasons Tool tend to take so long between albums.

"We rarely write in the studio," says Carey. "Everything's already completely arranged before we go in. That way, we can really focus off getting the recording right."

Justin and I are always writing, and then Dan and Maynard bring

|

in their own ideas about how to approach what they do," says Jones of the band's writing process. "And then we tear it apart like wolves, and we study it and study it and study it. We go down all these different paths and explore it. And then we go, 'OK, this path and this pith-that really works.' And then we start connecting the dots. It's a long process, but it works, man. It fucking works."

As on previous records like Lateralus and 1996's AEnima, Keenan's vocals on 10,000 Days often sit so low in the mix that it can be difficult to make out his words, at least on the first few listens. This, like just about everything with Tool, is purely intentional.

"I'll talk to people from other bands," says Jones, "and they'll say, "Your sound is so huge! How do you get that?' And then I hear their stuff and the vocals are way out front and the band's in the back, and that just makes the band sound little. It's a fine line. Maynard is an instrument, but you have to hear what he's saying, as well."

"It's definitely not a Backstreet Boys mix," Keenan agrees. "I think sometimes the lyrics tend to take you out of the headspace of feeling the song. That's kind of why we don't print the lyrics to begin with - reading is a thinking process, and if you're looking at the words, you're not really listening to what's going on. Also, in the song, if you're distracted by a very specific storyline, then you're listening to the story and not the song. We're not doing 'Paradise by the Dashboard Light.' We're not really that kind of band."

Which is not to say that the enigmatic singer doesn't invest a great deal of thought and emotion in his lyrics, or that there's no particular theme or meaning behind 10,000 Days. "It's all about my trips to 7-11," says Keenan with a wry grin. "We toyed with calling it I Smell Poo, but we couldn't agree on how to spell 'Poo,'" he chuckles. "Star Wars 7 - that was another possibility. We figured it would make for a good tie-in, commercially."

All joking aside, Keenan says that the album reflects the increasing disillusionment he's felt in the wake

of George W. Bush's re-election, and his frustration with what he sees as an American populace that seems unwilling — despite a steady stream of scandals and screw-ups— to get off their collective asses and drive Bush and his corrupt cronies out of Washington.

"On our last few albums, there's been more of a metaphysical, attempt-to-open-your-third-eye kind of approach, having faith that people will find a way to expand their consciousness and wake up to the world that they live in," he explains. "For some reason, we felt like we could help 'cm with that. And I think over the last few years, I've either gotten older—or become the grumpy guy who keeps your ball when it bounces in his yard—but I think I've lost a little faith watching the whole political thing.

"Looking back, I was just a little kid living in Ohio when there were students getting gunned down on campus because they were speaking their minds," he continues, referring to the Kent State massacre of 1970, when U.S. National Guard troops opened fire on a group of college students protesting the Vietnam War. "And it seems like nowadays, people sign a petition online, or they send an e-mail. That's about as much as they can do, and it's a little depressing to me. So I've noticed that this album has a lot more sadness on it. We've been joking about it in a way, but this is kind of, like, our blues album. There's still a lot of hope in it, and there's still a lot of positive, fun, silly stuff But if there's a theme to it, it'd be. 'Hey, you can lead a horse to water, but you can't make him drink. I have witnessed this firsthand—and therefore, you're on your own.'"

"IF YOU REALLY SAT down with the four of us," says Jones, munching on pasta salad at a recent Revolver photo shoot, "you'd find out that we all listen to very different musts We all have different influences We all have different political views. We all have our own thing, you know? But what we do is meet, in the center and explore that area—that's the

|

thing that works, and we're very happy with that."

Tool arc indeed made up of four distinctive personalities. In person, Jones comes off as articulate and self-deprecating, with a gleam in his eye that's part mad scientist, part merry prankster. Chancellor, the band's lone Englishman, seems quiet and intense; between Lateralus and 10,000Days, the bassist took up surfing and sailing in order to "clear his head" for work on the new album. Carey is a jazz fan with a boisterous laugh and a matter-of-fact manner of speaking that reflects his Kansas upbringing. And then there's Keenan...

While diehard Tool fans understand that the band's musical magic is the product of its four-part alchemy, the media generally tend to focus on Keenan. Though he appears small and self-contained in person, Keenan casts a large shadow with his outspoken interviews and his charismatic stage presence — not to mention his penchant for performing in a variety of strange wigs, costumes, and the occasional pair of prosthetic breasts. For the past six years, Keenan has also done double duty (and garnered additional critical raves) as the frontman of A Perfect Circle, a project he co-founded with guitarist-songwriter Billy Howerdel. For Keenan, the concept of

downtime doesn't seem to exist. After the Lateralus tour cycle, for instance, when the rest of his Tool mates were recharging their batteries, Keenan was busy recording and touring with APC.

"It was like the second time he jumped right out of our bus and into that thing," says Carey with a laugh. "He hasn't had any time off in, like, eight years."

The conversations that I'm having with those musicians are completely different from the conversations that I'm having with these musicians, so it's pretty easy," says Keenan of splitting time between APC and Tool. "If you're a creative person, you realize that that creative force is there for the taking, if you just tap into it. The energy is there, and the creativity is just an infinite pool of light that you can just draw from."

Though his A Perfect Circle commitments kept Keenan out of the Tool rehearsal space during much of the writing of 10,000 Days, Jones says the singer's absence didn't hold the band back at all. "About half of the songs were forming while Maynard was on tour, and that was fine," the guitarist recalls. "When we're writing, there's usually points where Maynard's going, 'OK...now where are you going with this?' It's good having him there, but it can be tedious for him to be there while we're still working all of this out. To" use a painting analogy, Maynard can paint something in a day or in a week. I have to paint, and then repaint, and then I go, 'Do I really like it?' And then I sand this part, paint some more...and we drive each other crazy like that. So him being on tour gave. us both the space to approach what we do best the way we do it."

Still, Keenan admits that juggling

both bands finally wore him out. "I've been going back and forth with Tool and A Perfect Circle for a while," he says. "But Billy is going to be doing his own thing now, and I'll be focusing mainly on Tool." According to Keenan, making music was the easy part, but dealing with all the attendant industry crap was really starting to bring him down. "It's just too much energy to deal with two completely different sets of lawyers and record companies," he says. "To try to explain who you are to a whole new set of record company people who weren't there last time and are afraid of losing their jobs, who aren't really going to go out on a limb for you and don't have any idea what you're doing.

"1 mean, none of these people know what I do," he continues, vitriol rising in his veins. "It's like, I'll tell them, '1 have a winery,' and they're like, 'You do? Well, what the fuck do you do? How are you getting paid?' Just type my name into the Internet, and you'll find out what I'm up to. Fuck! I mean, there's so much going on in my life, you would think that a publicist would be milking all of that and sec an opportunity to get that out there, because the record company is the one whose survival hinges on the sale of our record.

| |||

| |||

|

I can go tour. I'm gonna make my money on the road—all I've gotta do is get onstage, and I will pay my rent, and everything's fine. If I don't sell one more fucking record, I can still make a living performing. But the record company needs to know what I'm up to. And when they don't, it fucking blows my mind!

"You know that whole 'end of the world' scenario, where you want to gather people together to go to your little so-called oasis or island?" Keenan asks. "There's a hell of a lot of people I'm not bringing! You know how to heal somebody? You know how to cook? Do you know how to hunt? Do you know how to raise babies? Do you know all about gardening and herbs? Great, you can come with me. But if you just drew a paycheck at a publishing company, I'm gonna cat you! You're dinner! I'm sorry, you're gonna be in the compost pile, and when it comes time to plant next year's crops, you're gonna be the fertilizer."

AS OF PRESS TIME, Tool's first live performance this year will be in late April at the Coachella Festival in lndio, California; the band will spend much of the spring and summer playing festivals in Europe, followed by a headlining tour of the U.S. in the fall. "We'll just see how the record does," says Jones modestly. Adds Carey: "We just hope that, if people like the record, they'll come to see us. People know they're going to see a good show when they come to see Tool. We've established that over the past 10 years or so, so they know they can't go wrong there. Even if they don't like the record that much, they know they're going to see the next best thing to Pink Floyd."

While it's weird to hear a band that's sold millions of records downplaying commercial expectations for their new album, the fact is that the music industry has changed considerably since Lateralus was released. "It's hard, the way the industry is now to do what we do and still fit in," Carey admits. "We are one of the last truly alternative bands, now," he says with a hearty chuckle. "Making 13-minute tracks is pretty alternative, I think!"

And, then, of course, there's the issue of whether or not the iPod Generation has the attention span necessary to digest a work as dense and lengthy as 10,000Days. "Well, they still have the option, you know?" shrugs Chancellor. "We're providing them with the option to ". do that, rather than just providing them with single tracks because that's 'what's happening.'"

"I'm not in their heads," says Keenan of young music consumers. "I'm just not that guy. All I can do is do what I do, and do what feels natural, and be in that space that makes sense to me. If, for some reason, that translates to a 16-year-old, then I've still got a career. When it doesn't, I'm a dinosaur and I'm irrelevant, and I'll probably be at the age where I'll be OK with that. The locus [when making a record] is to be

honest with where you arc right now, and report the stories of where you are and how you feel right now. And if you can honestly report those feelings and capture those moments, then it's a great album. Don't worry about what you did back on previous albums, because your state of mind there is not where you are now. If we try to report the process that we had at 25 at the age of 35-plus, then we're being dishonest, and it's not going to come across as genuine."

That "be here now" attitude has definitely served Tool well over the years and may be one reason that their legion of fans keeps growing even as the band continues to defy categorization. "We're so lucky," marvels JONES: "At our shows, you look out and you've got the older generation and we've got our peers and we've got the younger generation, and then we've got the tots that are just coming into it."

"We won the lottery," says Keenan. "The thing is, a lot of people win the lottery, and they just take all the money to Vegas and wind up drunk and broke. We won the lottery, and then we reinvested, and we reinvested, and we reinvested. We maintained focus. The goal wasn't to win the lottery. The goal was to take that success, and work v as a tool. And that's what we're still doing. "

|

|

|

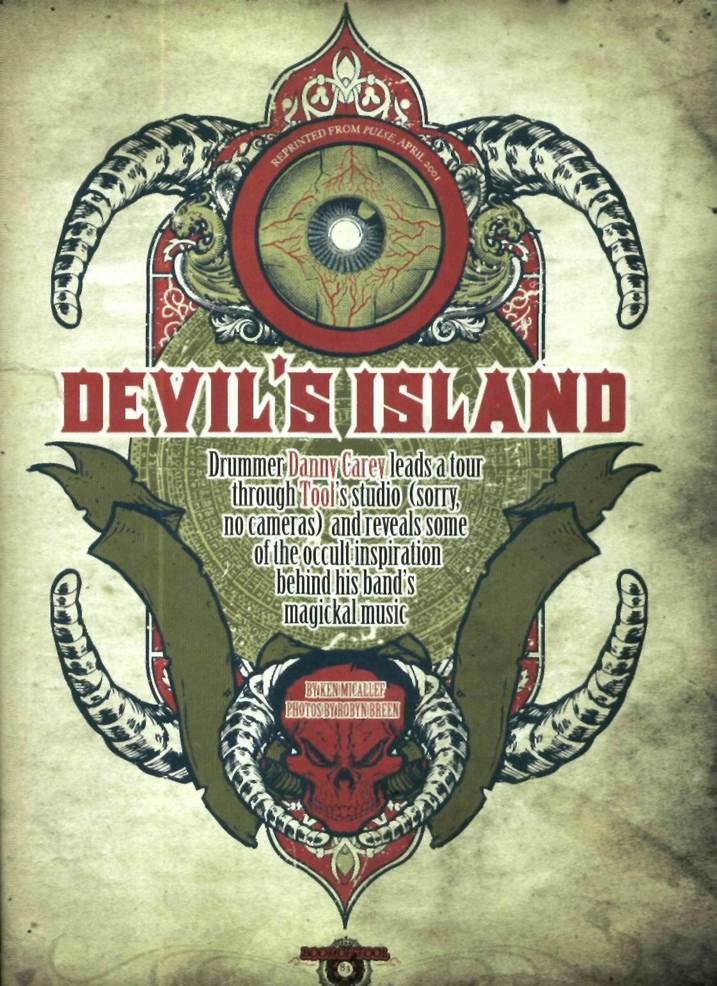

YOU CAN TELL A LOT

about someone by visiting their home and place of business, right? If you had stopped by Jeffrey Dahmer's cramped apartment in the early '90s you might have noticed something oozing from the fridge. Or John Wayne Gacy: Beneath his clown costumes, construction contracts, and floorboards you'd have whiffed the pungency of decomposing flesh. And so it goes with rock bands. Visit Abbey Roads Studios - you'll see where the Beatles once walked. Travel to CBGBs, where the Ramones reigned. Enter the disheveled Hollywood studio lair of progressive metalheads Tool and you'll discover all manner of occult regalia and maybe even a whining demon or two.

Greeted at the studio door by Tool's drummer and resident occultist, Danny Carey, you're led down

a dark passage, then into the studio and a lounge with couches and a massive sound system. A huge geometric grid covers the ceiling, which is also decorated with gargoyles and skulls. Two 100-year-old swords once used by Carey's father in Masonic rites adorn a wall, with more geometric patterns, a mace, an occult library with umpteen first-edition Aleister Crowley books, a bronze Szukalski sculpture, framed photos of Aphex Twin and ELP's Carl Palmer, and an unusual Jacob's Ladder, a sci-fi contraption from a '50s Frankenstein movie. Over in the studio, in addition to a wall of guitars and amps, an enormous "Enochian magic board," inscribed with the names of various angels and used to channel spirits, is lodged behind Carey's drums. The lounge is strewn with more dissimilar objects-talking drums, a zebra-skin recliner, ancient masonry fragments. The place is a maze of secrets. But can these secrets be revealed to just any visitor?

"It is fine to be open about some things," responds Carey. "Other stuff should be shielded from the eyes of the profane." He laughs. "1 was raised with that element from my father, so I've always looked farther than what people were telling me. It is mainly just research for myself. It takes stamina; sometimes you have to face

things you don't want to face. But that courage is always rewarded, J have found."

Courage and strength arc what the members of Tool-Carey, singer Maynard James Keenan, guitarist Adam Jones, and bassist Justin Chancellor-needed to complete Lateralus (Dissectional/Volcano). the band's most monstrously powerful and progressive album so far. Spending two years in a drawn-out court battle with its former record label has only strengthened the band's resolve. Lateralus is the year's most densely idea-packed and overwhelming album, a pounding epic of six-minute-plus songs infused with ritual themes, tribal drum solos, sweltering guitars, extended improvisations over taut odd-metered rhythms, and howling tortured vocals that bellow occult messages, all shrouded in the otherworldly aura of some demonic sacrament. That's right, another Tool album. But compare with 1996's AEnima, Lateralus is far more circuitous, engrossing, and apocalyptic, like the bastard child of Starless and Bible Black-en King Crimson and Black Sabbath.

Дата добавления: 2015-10-23; просмотров: 79 | Нарушение авторских прав

| <== предыдущая страница | | | следующая страница ==> |

| WHEN THIS WRITER FIRST INTERVIEWED 4 страница | | | WHEN THIS WRITER FIRST INTERVIEWED 6 страница |