Читайте также:

|

TURNER: Were you in the army? KEENAN: Yeah.

TURNER: You're coming from a fairly liberal point of view. Do you feel like it was really important to have lived on the other side?

KEENAN: It was absolutely an important thing. Because, as you know, there's some pretty dumb people in the world. And the dumber they are, the more violent or reactionary they can be. And so you need to defend yourself. Put your fists up if somebody's gonna swing at your face, for God's sakes. So, having been in the military, I understand that there are monsters in the world. We're all made from the same stuff, but some of them just don't have the direction and education. And environmentally and historically, that's just not gonna be fixed. There's just too much crap in the way. So no amount of hugging and flowers in the barrels of guns is gonna change any of that shit.

JONES: No amount of going "No war!" All right, then let's get rid of our police and have no crime! It'll be magic!

TURNER: Do you think we're currently on the precipice of some sort of implosion?

KEENAN: This is totally my opinion, but I think that the only reason that we as the United States have not imploded earlier is just geographic isolation. If we were attached to anything, there would have been huge mobs of armed people making changes. But because of our physical isolation, we can see everything coming. With satellites, we can see anybody coming up from the south or down from the north. We're somewhat safe, and that's the reason why terrorism is so effective, because you don't sec that one individual coming. Just looking historically, something's gonna break soon and change. The smart thing would be to be aware of it and learn to speak the language of the next regime. Or be able to present them something-"Look I made some fecal-free spinach for you!"

TURNER: Considering the cycle we're in now, and the position that the government has currently put itself in, would you enlist in the army today?

KEENAN: Hell, no.

GALLAGHER: I don't think I would either.

KEENAN: Vietnam was when I was a kid. I was living around the Kent State area, so I was right around the area when the students were being gunned down while I was playing Army with my friends seven miles away. [When I enlisted,] all that backlash of Vietnam was settling down. You would think that based on what had happened in that jungle setting, that we would be doing that tropical/jungle training. And we weren't. In 1982, we were doing desert training. There was an agenda hack then for this area [the Middle East]. They're so far ahead of us in what they're telling us and not telling us. There's no way to sec the big

picture. So once again, our idea is to just drop back and be a conscious human being.

GALAGHER: My perception of you guys in the beginning is that you've always done everything your way...

JONES: That's an outside perspective. You have to realize the decision process we go through, the difficulty we go through to find that middle space where we are all compromising. Because that's the process we take — we just don't have the headspace or the time to worry about what other people say. This is the only way we can do this. It's not a conscious decision like, I'm not gonna listen to you, and I'm not gonna do it that way. It's just the way it is. It's just the way this big barge floats through the bay.

GALAGHER: Has that caused problems with labels?

JONES: There's tons of manipulation on that side and tons of people taking advantage of your ignorance. Our hands have been burned in the pan so many times.

TURNER: The reason that it's an interesting question for us is that [bis] come from a realm where those pressures are relatively low, but we've come to realize how marry outside pressures there are on a band.

KEENAN: Like, "You guys should lose that member because he's holding you back."

turner: Or, "You guys should write shorter songs." Or, "You guys should write more conventional structures." In pretty much every way, you've defied conventional norms. And like you said, it's pretty much your natural M.O., but in another way, you're in a world where it's almost impossible to escape those pressures. So to us, from an outside perspective, that's admirable. To us, it's interesting to see that in a world where everyone basically plays by the same rules, you guys have gone upstream from that consistently.

KEENAN: The analogy that you always hear when you have to sit around listening to people constantly bringing up Limp Bizkit and Fred Durst to you over and over and over and over again is that old Chinese proverb: Patiently sitting on the banks of the river, watching the bodies of your enemies float by. We're not necessarily going upstream. We're sitting still; the stream's just moving. And that's what's kind of messed people up— "Aren't you struggling?" No. not struggling. We're just sitting in

|

space that we sit in. and everything's moving around us.

TURNER: To me, it seems that the bunds that are most resistant to outside pressures are often the with the greatest longevity. The Melvins, for instance. Those guys have been through every label situation in the world, and they've pretty much always stuck to their guns. And they've been a band for, what, 20 years?

GALLAGHER: Twenty-three now. JONES: They're one of those bands. Strummer, you know, no one gives a shit. Then when he dies... The Ramones. Johnny Cash. Oh, now he's this big phenomenon. People take it for granted. The Melvins will definitely be that band. [Singer-guitarist] Buzz [Osborne] will kick the bucket, or [drummer] Dale [Crover]. Then they'll break up, and people will be going. "Oh, my God, the history of grunge. They were part of that whole thing."

TURNER: Well, it's a business thing. Primarily, bands arc interested in making art and making music. And most musicians aren't cut out to be business practitioners. So, very often, they get taken advantage of, and they don't know what the fuck is going on.

KEENAN: Which half the time is a good thing, because you give those people too much money and they stop making fuckin' music. They implode. They don't know how to handle it. If Axl Rose was still fuckin' hungry, there'd probably be an awesome third album. Go back to pumpin' gas because it was w aaaaay better.

JONES: I was talking to Buzz, and there's this book that this lawyer wrote [about] how to make it in the music business. But it's written from the other side of the fence. And, seriously, if you read it, it's like: This is how you take advantage of a band, this is what a band doesn't know, this is how you can "help" the band. I said, "Hey, why don't we write a book from the musician's side? Realty help the up-and-coming musicians." And he went, "Yeah. That'd be cool." Then he went, "It'd have to be a comic book. And no one would read it."

KEENAN: You'd have to put an X rating on it because you'd have to have pictures of bands being ass-fucked by some big, hairy fuck with a cigar. Illustrations of ass-rape throughout the whole thing.

TURNER: From the realm we come from, we've seen a lot of so-called "indie" labels basically perpetuating major-label scams on really young bands, like signing them to eight-album deals.

JONES: It's, like, life. Anything that you choose to do and any kind of success you have, you're gonna have those obstacles. You're gonna have those people hanging out with you for the wrong reasons. You're gonna have corruption in your bookkeeping and all that stuff. It's just part of the chaos you have to deal with. My experience talking with other bands is they don't wanna deal with business issues. "Don't tell me anything bad. Just tell me what's good, and hopefully I won't end up on VH1 going, "Had it all. Lost it all. Now I'm trying to get it back."

JONES: "What happens if you don't make it?" "What do you mean?"

KEENAN: "You have to see our band, because you would understand if you would see our band, because we're gonna make it. Here's some tickets that we had to pay for. We're playing at the Whiskey." You guys didn't have to go through that pay-to-play thing, did you?

GALLAGHER: No. Thank God.

JONES: Every club was like that. They'd say. "We give you the tickets. You pay us for them, and you have to go sell 'em to people."

GALLAGHER: Fuck that.

TURNER: I'd rather play to nobody.

KEENAN: "Well, it's worth it to buy the tickets because once these people see you. dude, it's gonna blow up!"

JONES: This is a mean thing, but when our band started getting popular, we started meeting a lot of A&R people, so

we'd keep their cards. And then you go see some cover band and go. "Dude, call me tomorrow!" and hand 'em the card and walk out. [Laughs] We did that all the time.

KEENAN: "You guys are amazing. Give me a call. My name iiiiiis..." GALLAGHER: In playing an arena or amphitheater, do you feel like you guys are able to connect with the fans as much as you would like?

KEENAN: The club setting is really intimate, and there's a nice energy in that setting. But when you do an amphitheater, the way that it's set up, it just ends up being more, um, money. [Everyone laugh]

TURNER: Is it old hat to you guys now, or do you still get a charge when you walk out and there are, like, 20,000 people screaming their heads off?

KEENAN: Who needs Viagra?

JONES: I love it. I get weepy.

KEENAN: Except for the creepy guy in the third row with the binoculars. What do you need to see?

GALLAGHER: When you guys arc waiting before the encore...

TURNER: The lighter routine!

GALAGHER: I'd seen that shit when I was 15 a hundred times. Oh, whatever, lighters. But the first time I saw it [on this tour], I was like, Oh my God! It was moving to roe, and I had nothing to do with it.

|

|

|

|

SOMETIMES, SINGING songs about choking infants, swallowing poison, and rotting in an apathetic existence can get kind of stressful. So every now and then, Maynard James Keenan likes to get away from it all. He comes here, to this sanctuary in LA's San Fernando Valley - a picturesque setting where he can relax, contemplate, and just, well, have a little Maynard time.

The place, known as CityWalk, is an outdoor food-pavilion-cum-strip-mall-cum-amusement-park, a consumer flagship to the Hollywood megalopolis Universal Studios. Just three minutes from the recording studio where Keenan's band Tool are completing their ferociously awaited new LP, this immense shrine to ill-advised spending greets us today with Lenny Kravitz blasting from inescapable speakers. Sidewalk vendors hawk airbrushed portraits of Tupac and Barbra Streisand, while the ritzier stores

offer action figures, Pez collectibles, [link fudge, and other essentials. Kids scamper, Moms scream. The migraine countdown begins.

"This is as close to hell as Earth gets," says Keenan, edging down the prom-enade. He looks left, then right. "When

it's crowded, it's almost intolerable," he continues. "You want to get out a rifle, stand on a building, and...erase the karmic debt, so to speak."

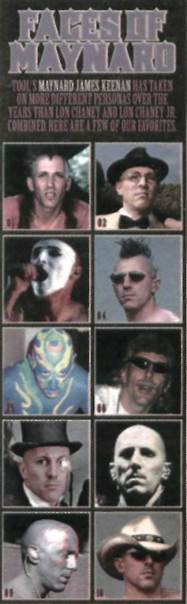

These words do not come from some dreadlocked goth-biker, tattooed B-boy, or any of the stock figures fronting "heavy" rock bands these days. A bantam 5-foot-7, Keenan walks through the crowd this afternoon with a shaved head, black Nike warmup suit, and the nervous, wide-eyed expression of a Jack Russell terrier. He has the dark stubble and generous nose that casting directors would label "ethnic-looking." He might get picked to play a streetwise informant in a cop show. He would probably not be cast as a singer who has captivated millions of metal-mad concertgoers and motivated one of rock's most rabid cults with two different bands: Tool and their new competition, A Perfect Circle, which Keenan formed with pal Billy Howerdel and whose debut has gone double platinum.

In fact, given his preference for costumed performances and unpeopled videos, Keenan is pretty much the sole rock megastar who's virtually unrecognizable, even to his fens. "Once, [Tool guitarist] Adam [Jones] and I were leaving the Hollywood Palladium after seeing a show," he recalls. "And after we said goodnight and split up to go to our cars, some kid runs up to me, frantic — 'Oh my god, oh my god, oh my god, were you just talking to Adam from Tool?' I was like, 'Yeah, he's cool, you should go talk to him. He might take you out to dinner.'"

If Keenan's look isn't familiar, the sniper sentiments should be, at least to fan's of Tool's last record, 1996 's AEnima, whose title track longed for a natural disaster to strike "the hopeless fucking hole we call L.A." and sweep away "millions of dumbfounded dipshits." As singer and lyricist, Keenan has found a way to transmute such thoughts - rueful, surreal, mordantly hilarious —

into a classic kind of Zeppelin-esque drama. He now heads one of the last surviving heavyweights of the artistically ambitious hard-rock '90s, a shadowy dirge-metal outfit whose songs chum along in tightly orchestrated blasts of eerie sound and fury and whose spectacularly dark videos (like "Prison Sex" and "Stinkfist") have almost never featured any members of the band.

Concerts arc a different story. "You can count on one hand how many bands of today have great frontmen," says Sharon Osbourne, wife of Ozzy and organizer of Ozzfest. "Maynard is definitely one of them. He has one of the best voices out there, and he's just so creative. You don't know what to expect when you see Maynard. He's just amazing." Plus, the man realty knows how to accessorize. Keenan's stage attire has included bustieres, long blond wigs, blue and white body paint, prosthetic breasts, Speedos, a wheelchair, and the shiny, wide-lapelled suit of a tel-evangelist. (Wearing the latter, he began one concert waving a limited-edition. gold-plated Bible, which he later hurled into the crowd.)

Yet here today, Keenan appears as unremarkable as any other wiseass hipster goofing on tourist traps. When we come

|

|

upon the novelty store Out-Takes, which uses digital imaging to put customers' faces onto movie posters and magazine covers, Keenan considers a tireman torso from Backdrafi and a hunk on Muscle Fitness. He finally chooses the poster for the recent 102 Dalmatians. "I'd get Glenn Close's body," be says. "Which I guess is good."

upon the novelty store Out-Takes, which uses digital imaging to put customers' faces onto movie posters and magazine covers, Keenan considers a tireman torso from Backdrafi and a hunk on Muscle Fitness. He finally chooses the poster for the recent 102 Dalmatians. "I'd get Glenn Close's body," be says. "Which I guess is good."

After the attendant scats Keenan before the blue screen, something strange happens. With his hands calmly folded on his lap, Keenan begins to change. His coal-black eyes start to glimmer, as if staring off at some distant horror. The corners of his mouth ease downward, finding the look of a frozen death mask. The shutter snaps. The pose breaks. The attendant and ha co-workers burst into applause.

A minute later we get the photo. Sitting atop the fur collar of the Disney diva, Keenan's face evokes less Cruella De Vil than a classical depiction of some mythological tragedy. His look of unspeakable anguish suggests the martyred St. Sebastian pierced by arrows, or Prometheus chained to the rock, his liver devoured by an eagle. When I ask what he was going for with that particular character, Keenan shrugs.

"Well, I was just trying to capture what Glenn Close was probably feeling during the filming of 102 Dalmatians," he says. He looks at the photo for a few seconds. "This could be titled 'I Smell Dogshit."

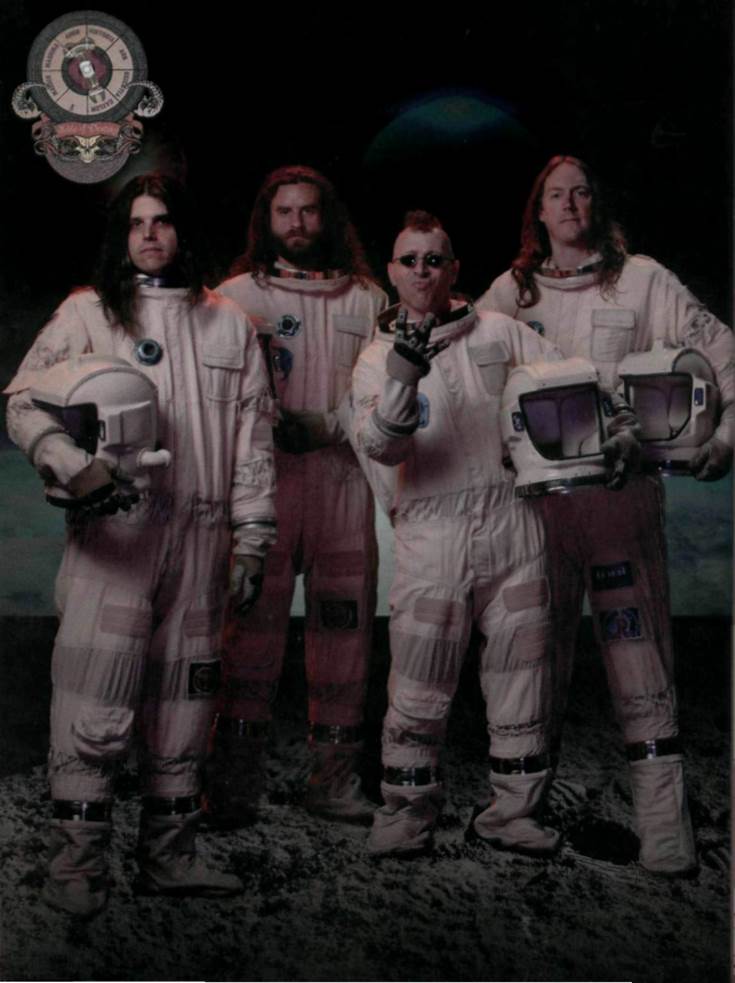

ON A FINE, SUNNY JANUARY

day in Los Angeles, the members of Tool are, fittingly, holed up in the dark. They're huddling over a mixing board with producer David Bottril, whose other clients include King Crimson and Peter Gabriel, putting the final touches on Lateralus. It's a disquieting time for Tool, partially because, as they stand up, blink, and look around them, they realize they're the sole survivors of the Hard Rock Class of '93.

"Alice in Chains, Helmet, Soundgar-den, Nirvana, and now Rage Against the Machine," says drummer Danny Carey, a tall, surfer-ish guy with dirty blond hair who hails from a small Kansas town. He lets out a long exhalation. "It's really kind of amazing that all of them are gone." Bassist Justin Chancellor sits next to him, with dark, shoulder-length hair, a brush of beard, and dark-circled eyes. "We can definitely understand: It's hard to keep a band together," he says in a low voice with a Northern English accent vaguely teminis-

cent of Derek Smalls'. "But in our case, it's just worth it."

Keenan says that mutual respect, more than shared tastes (Jones digs death-metal extremists Meshuggah; Keenan's more into the Bulgarian Women's Choir), has been the real source of Tool's longevity. "What we have in common is the ability to listen," he says. "You just listen to each other and find some space in the center. And if there isn't room for you there, then you wait until there is."

But three years ago, when the other three members of Tool were finally ready to start work on Lateralus, they found a bit more space than usual. "Maynard was gone for a lot of it," says Carey. "Off doing his Perfect Circle thing," Chancellor adds. "We didn't quit working because he was away. He was around jamming for a while. But (here was a while where he was off and it was the three of us." The band's usual mode of working is to make the music first and add lyrics last, so they got much of the music done while Keenan was away. "It's somewhat unusual," admits Carey. But if there's tension here, no one is copping to it.

And so we have the setting for Tool's comeback, the drama "behind the music." Four decade-long friends grappling with. changes, facing down rivals, and trying to reestablish some kind of connection with each other. It isn't smooth sailing, but that seems to be par for the course. After the release of AEnima, Keenan told a reporter, "Every aspect of what we do-each song, each video, each album cover — is tortured over by each of us. Nothing comes easy for this band." In earlier interviews, Tool would often refer to a book called A Joyful Guide to Lacbrymology, whose existence is dubious. Nevertheless, it is said to advise: "When there is no pain, there is neither the reason nor the desire to think or create."

Well, it seems Tool still have found reasons to think and create-a lot. Explaining the title song, Keenan says, "The core of it is lateral thinking. And the human clement of the spiral, the lateral." Carey helpfully adds, "It was originally titled "987." For the time signatures. Then it turned out that 987 was the 16th step of the Fibonacci sequence [in which each integer is equal to the sum of the preceding two]. So that was cool."

If your sensors arc detecting nerd life on the planet's surface, that's understandable. The widely suspect genre known as "prog rock" has a few defining characteristics. Time signatures in odd numbers. Songs that stretch over seven minutes. Song titles like "Parabola." Tool's latest has them all While "math rock" is the term used to describe any eggheaded. metrically ambitious band, these guys have a math-rock song that's actually about math.

Keenan insists otherwise. The new songs use the constructs of math and science only as metaphors for human lives. "They're all about relationships," he explains. "Learning how to integrate communication back into a relationship. How are we as lovers, as artists, as brothers — how are we going to reconstruct this beautiful temple that we've built and that's tumbled down? It's universal relationship stuff."

Unlike on earlier Tool records, Keenan found these lyrics — in a sort of Freudian free-associative way — from scatting lines and responding to the emotions suggested by the music itself, which rises, ebbs, and crystallizes with a nearly Beethoven-ish deliberation. The debut single, "Schism," builds a rippling arpeggio into a heady harmonic-minor groove. The title track begins with an ominous, Autechre-ish pulse and morphs it into a tightly packed metal riff, as Keenan's lyrics chart a history of consciousness over digitally triggered tablas and congas.

Lateralus is the work of thinking, optimistic adults who still have the gee-whiz eagerness of tinkerers, guys who have gone beyond purging adolescent baggage and are struggling, musically, to find the next phase. And the stakes for the struggle are

high, since a beloved band, and some very intense friendships, lung in the balance.

ELEVEN YEARS AGO, FOUR

artsy, self-effacing guys in Los Angeles formed a band, a quartet their liner notes would list simply as "Geeks: Danny Carey, Justin Chancellor, Adam Jones, Maynard James Keenan." Jones was working in the film industry, doing special effects work for films like Terminator 2 and Jurassic Park. Carey and Keenan were sidemen in the joke-metal act Green Jelly (ne Jello), the latter making his vocal debut as the falsetto voice of one of the three little pigs. The three met bassist Paul D'Amour, who was later replaced

|

| They're also a bitch to make. Which partially explains why fans haven't heard from Tool in five years. |

by Chancellor.

Under a rubric befitting a '30s Russian art cabal, this collection of King Crimson and Black Sabbath came to transcend the genre of "heavy" music.

Keenan's morbid telegrams from the subconscious-"I am just a worthless liar / I am just an imbecile"-were complicated by his distinctive vocal ambiguiry -the eerily sweet, calm voice of a troubadour giving way to one of the all-time great metal shrieks. Their songs, tortured enough to merit comparisons to goth titans like the Cure and Nine Inch Nails, struck a chord with a nation of bummed adolescents. In 1993, after an appearance at Lollapalooza, they exploded. Opiate, released in 1992, 1993's Undertow, and 1996's A Enima have all gone gold or platinum;

the recent multimedia set Salival has sold 250,000 copies. "I can't name any other band that measures up to the kind of credibility that Tool have," says Lisa Worden, music director at L.A.'s KROQ. "They never compromise any of their beliefs and interests as far as what they Want to do. They have built this completely loyal and huge fan base, and it just continues to grow."

The fans come in all shapes and income brackets. "Tool's probably the best band, I think on the planet," Fred Durst told MTV News a little while ago. "There's something wrong with those guys. They're too good. They know something that the rest of the world doesn't know.... I can't even be in a category with that band."

With this last point, the members of Tool would probably agree. The world of hard rock has undergone a profound change since Tool were last on the scene. Not only are Jungian discourses and Fibonacci sequences pretty far from the concerns of most of today's nu-metal bands, but even the ideas of "pain" and "dysfunction" have been devalued. They have become prepackaged flavas, sampled emotions, which have perhaps found their most extreme reduction in a couplet by Nirvana-loving rap-rockers Papa Roach: "Broken home/All alone." Sing in verse. Scream in chorus. Jump up and down.

Such digitized packets of fun'n'angst have little in common with Tool records, which are not cursory, МР3-singles-on-CD fan-club accessories. They are weighty, mysterious testaments from afar, lull of philosophy, jokes, weird sounds, shifting imagery, and odd meters.

Chalk the rest of the wait up to business as usual. Three years ago, Tool were forced to deal with corporate restructuring at their label, Zoo, followed by a suit from their manager of seven years, Ted Gardner, co-founder of Lollapalooza. Gardner filed a $5-miliion-plus action against the band (for rescission of management contract, fraud, etc.), and the collective shit storm that ensued preempted music-making for, literally, years.

To escape the legal chokehold, Keenan formed A Perfect Circle with roommate, guitarist, and Tool tech Billy Howerdel. "All the litigation and stuff was just crippling," Keenan says. "I just had to go do something." Their debut, Mer des Norm, delivered the killer industrial-rock single "Judith," whose "Fuck your god, your Christ" chorus provided withdrawing Nine Inch Nails fans with a mainline dose of tuneful blasphemy. The entire record revealed a potent songwriting team in composer Howerdel and lyricist Keenan, and one with a potentially wider audience than Tool's. "I think people who listen to A Perfect Circle hear something totally different from me," Keenan says. "It's much more like the Cure. It's more ethereal and accessible. Also, I think a lot of Tool fans weren't aware that I could sing."

If A Perfect Circle are giving Keenan an outlet for his more ethereal side, they're also seriously complicating the story of Tool. In fact, the two bands arc so skittish about potential conflicts of interest that the other members of A Perfect Circle refused to be interviewed for this story. Which is understandable. The huge success of Keenan's new band is the kind that might typically bode poorly for a long-dormant prior commitment. But then, it seems, very little about Tool is typical.

THE HARD ROCK HOTEL IS THE HAPPENING place in Las Vegas. A brightly lit festival of gambling and booze, its jumping atmosphere and plush amenities cater to just about every stripe of weekend reveler except, maybe, rock fans, most of whom would likely find the Kurt Cobain quote "Here we arc now / Entertain us," stripped of irony and posted over the bellhop station, less than inspiring. It's hard to imagine how a casino could miss using the much more site-appropriate Johnny

Rotten line that ended the last Sex Pistols concert: "Ever get the feeling you've been cheated?"

It is in this modern Babylon that A Perfect Circle play tonight, plugged on the electronic billboard alongside "Caribbean Stud Poker."

The crowd features plenty of pierced thugs in Tool tees, alongside goth moptops. snakeskin pants, and the region's residual frosted showgirl hair. A pretty 25-year-old mortgage underwriter named Autumn explain» why she prefers A Perfect Circle to Tool. "Perfect Circle arc not so Satanic-sounding," she says. A longhaired devotee named Todd has brought his 10-year-old daughter Clarissa to the show. "This is our first Maynard experience," he says. grinning. An even more serious Maynard cultist offers facts about Keenan's performance ethic. "He's all about his costume," he says. "Every time they do a show, he's trying to teach you something."

Tonight, class begins with a lone violinist and an ominous Middle Eastern drone. Keenan alters wearing a long black wig under a dark watch cap, shirtless, in black glitter pants. Sharing lead vocals with Billy Howerdel. who looks like a slighter Billy Corgan with his shaved white head and tight crewneck top, Keenan stands rock-still between verses, hunched slightly, muscled, redoubtable, and-somehow-riveting. "He never blinks, dude," says our Maynard expert, scrutinizing the huge video screens on either side of the stage. "He never blinks."

Дата добавления: 2015-10-23; просмотров: 65 | Нарушение авторских прав

| <== предыдущая страница | | | следующая страница ==> |

| WHEN THIS WRITER FIRST INTERVIEWED 3 страница | | | WHEN THIS WRITER FIRST INTERVIEWED 5 страница |