Читайте также:

|

Brandon Geist

EXECUTIVE EDITOR

|

|

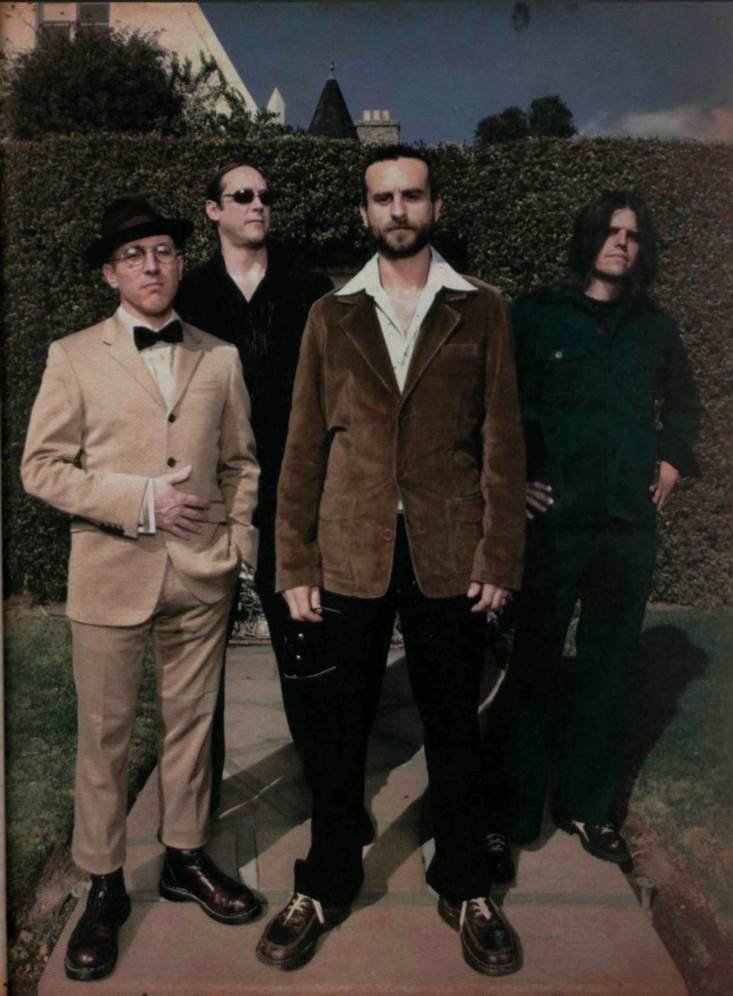

AN UNPRECEDENTED ORAL DISCOGRAPHY FEATURING

MAYNARD JAMES KEENAN, ADAM JONES, JUSTIN CHANCELLOR, AND DANNY CAREY

WHEN THIS WRITER FIRST INTERVIEWED

the members of Tool in 1996, drummer Danny Carey compared the band's creative process to the birth of a child. "It's chaotic and painful," he began. "Sometimes it seems like it's taking forever and it's brutal and harsh, but there's still a wonderful thing happening."

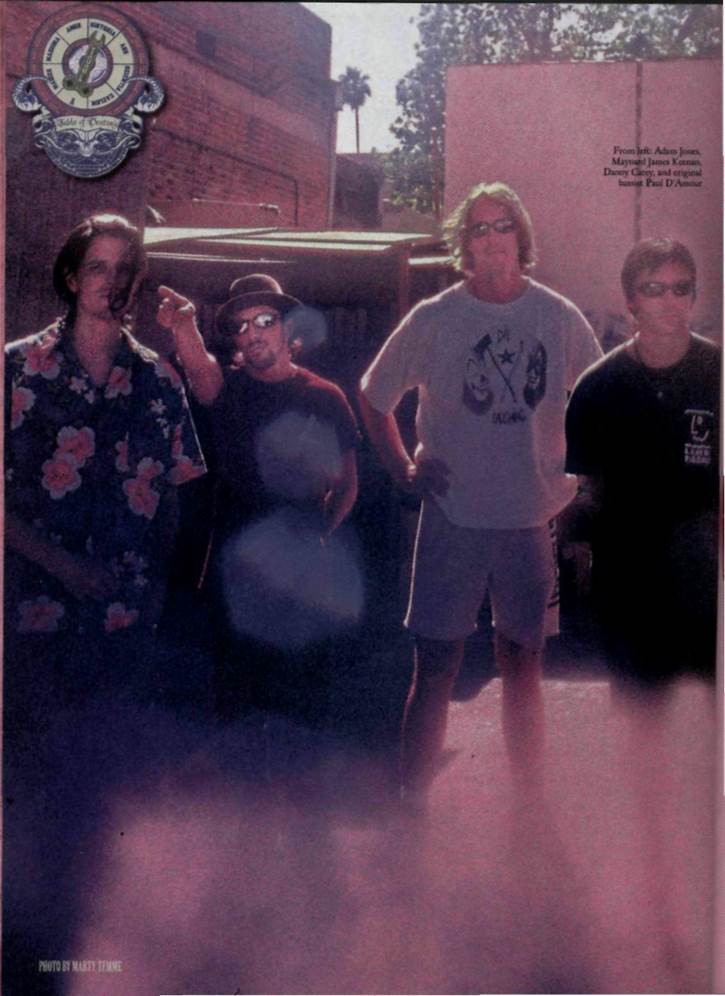

At the time. Tool had just released their second full-length. .AEnima, which entered the Billboard album chart at No. 2 and secured their position as the biggest progressive-metal band in the world. The creation of the disc involved endless jamming, plenty of arguments, a split with bassist Paul D'Amour, and the addition of new bassist Justin Chancellor. But compared with the chaos they would experience over the next decade, AEnima was a Cakewalk.

The band's next two albums. 2001' s Lateralus and 2006's 10,000 Days, taxed the musicians' patience and self-confidence to the point of near collapse, causing anxiety and frustration that was at times crippling. Singer Maynard James Keenan was unable to work in the studio with guitarist Adam Jones during the writing process for both albums, and personality conflicts between all four members became a major problem. Yet each time. Tool pulled together at the end and emerged stronger, more focused, and able to reach previously unimaginable artistic and musical heights. In his typically cryptic and eccentric manner, Keenan likens the band to a violin.

"Although it may sound beautiful, it's a very stressed-out piece of equipment," he says from his

home near Sedona, Arizona. "There arc all these pieces of wood, wet and bent and dried, and then strings stretched across them very tightly. And then you take this bow and you're dragging it across and you're making friction. But the voice that comes out of it in the midst of all that stress, friction, and tension — that's the beauty of it."

There is always a chance that the discord and conflict that both plagues and inspires Tool might one day tear them apart. For now, however, the members of the band continue to look beyond their pet peeves and endure each other's character flaws because they know the art they create together is far greater than the sum of their personal grievances,

"These musical, magical moments that happen when the four of us get into a room together-it's unexplainable." says Carey. "Maybe it's because we've shared so much in the time we've been together, good and bad. But that vibe takes place and it's Tool, and there's nothing else that will ever be Tool."

To track the development of one of metal's most cryptic and transcendent entities, Revolver spoke to all tour band members about writing, recording, and touring for each of their five studio discs.

BY JON WIEDERHORN

|

|

|

PRIMIT1VE BY TOOL STANDARDS,

PRIMIT1VE BY TOOL STANDARDS,

Opiate is still more developed and ,

expressive than most alt-metal records of

the era. Driven by youthful aggression and contempt, the songs lunge and hammer in repetitive, staccato bursts, but beneath the raw savagery is a tension that builds through clench-and-release rhythms, textural guitar waves, and vocals as pained as they are pissed. In his lyrics, Keenan sings about religion ("Opiate"). retribution ("Jerk-Off"), and reactionary hostility ("Hush") in raw, unrefined phrases. Despite its simplicity, Opiate features some clever arrangements that hint at the progressive path the band would later take. In the midsection of "Sweat," fast, double-bass drumming clashes with abrupt guitar blasts and an angular hook before the players latch back into the main riff, and on the title track, the band tempers its hostility with chiming, atmospheric guitar and eerily echoing vocals. The 27-minute EP features two live recordings sandwiched between four studio cuts but hardly suffers for its unconventional construction. There's also a goofy, psychedelic hidden track, "The Gaping Lotus Experience," that reflects the band's bizarre sense of humor.

DANNY CAREY: The vibe of the band was different at that point. We hadn't really defined the parameters between us or the way we interacted, and that made our sound more raw. There were a lot of boundaries being leapt over and lots more learning experiences happening at the same time, which was really exciting. Musically, we were just trying to find out what our personality was as a band. Sometimes I listen to my drumming from back then and it sounds like I'm overplaying, but that was the fun of it and that's sort of what turned us into the band that we are.

MAYNARD JAMES KEENAN: I was flying by the seat of my pants. My musical approach came from a lot of the frustration of living in LA., busting ass on video sets trying to survive. The music was all about emoting and releasing that primal scream. I was a big fan of Joni Mitchell and Swans, so I related more to that close-to-the-heart, personal lyric style. To me, songs really arc all about the story, and

|

|

| |||

|

|

|

|

that's why people respond to them. The music gets under your skin, for sure, but it's the story that puts the hook in and keeps you there.

CAREY: At the time there were all these hack

musicians playing crap that any garage band

could write. And when they made a video, they

had no choice but to show somebody's pretty

face or make them look cool and dance around

like a monkey, which seemed so embarrassing.

So we made a conscious effort to put our art

first and make it about the music and not the

musicians. And because our faces weren't

plastered over everything, people went, "Oh,

there's this mystique about Tool." That

continues to this day, but I think it's great that I can still go to the

grocery store and not get noticed.

KEENAN: It wasn't hard for us to get signed. We were four pretty pissed-off, relatively talented musicians, so we got a record deal after about seven shows. Of course, Nirvana helped open the door because

after they hit, most music guys around town were chasing their tails trying to find the next big thing. And here we come along, and we don't sound like most of the other stuff going on, so for them, they don't really get it, but they knew that it was different and that Nirvana was selling lots of records, so they knew they had to grab whatever it was, just in case.

ADAM JONES: The most important thing for us at that point was to have creative control. When we got signed, we went, "OK, if we take less money can we have control of the music?" And the label went, "Yeah, no problem!" And we said, "If we take even less money can we have final say over the videos?" And so on. But there was still a lot of banging heads with the record company, because they still wanted to do things in the traditional way. They'd go, "Well, if you're not gonna be in your video, we're not gonna pay for it." And we'd say, "What do you mean? We're supposed to have control." We signed a three-album deal with them and the first thing we wanted to do was an EP.

|

And they went, "Yeah, do an EP. That'd be great!" And we kind of got burned from it, because it wasn't a full album so it didn't count on our contract, which is why they were so agreeable when we first suggested it.

And they went, "Yeah, do an EP. That'd be great!" And we kind of got burned from it, because it wasn't a full album so it didn't count on our contract, which is why they were so agreeable when we first suggested it.

CAREY: We were broke at that time, and we knew that even if the record company was willing to pay for studio time, we were going to have to pay it all back. So we recorded Opiate in, like, four days because we knew if we were there longer it was gonna get expensive. But we also had a live recording and we were happy with the way it sounded. So we thought, Well, let's just mix the live tracks and add them to the record. We had been playing those songs live for a year, which is a luxury we don't have anymore. Now we have to keep everything secret, because we don't want to have people hearing our

songs on bootlegs all over the Internet. I wish we could still go out and play our songs live before we track them, but those days arc gone.

KEENAN: What I remember most about Opiate was just being in a space where other people had done things. I would look at the walls and see all the platinum records and that was inspiring, but it was also depressing, because you're taking this very first step in this life you're about to embark on, and you're looking at the wall going, Well, wait a minute. Where arc these guys now? What happened to them? So seeing these gold records on the wall from people we hadn't heard of, we kind of formed — unconsciously and in an unspoken way — a modus operandi for how we were gonna be, assuming that any second this thing was gonna end and we were gonna have to go back to our day jobs. And that modus operandi was to pursue our art and not be enamored or intoxicated by the unimportant stuff.

JONES: A lot of the songs for Undertow were already written when we did Opiate, but we felt like no one would take us seriously unless we recorded only our most aggressive, in-your-face songs and put them out there at one time. And I think that got us typecast as a metal band. It's kind of funny, because the song I thought was the least aggressive, "Opiate," was the more popular one on the record.

KEENAN: After the record came out, we'd find ourselves in someplace like Akron, Ohio, playing a club that could hold about 500 people, but there are only five people there and those are the guys that arc gonna play after you. That was awkward, but it didn't really matter to us because we were still getting to know each other. And in a way, not having any pressure to perform to anybody, you can just kind of explore your space right there. And as time went on, it became more about how we connected onstage and less and less about how anyone in the audience was reacting.

|

|

MORE COMPLEX AND MULTI-TEXTURED THEN OPIATE

Undertow is a fist-clenching hard-rock/metal album that marked the first major step in Tool's musical evolution. It also turned them into rock stars. The vulnerability of songs like "Sober" and "Prison Sex" struck a nerve with alternative-rock fans, and the overall heaviness of the tunes appealed to a new generation of open-minded metal kids. Not that Tool were catering to either. As always, they were driven solely by the need to experiment and explore and were limited only by their playing abilities at the time. So they made the most of what they had, crafting songs that were alternately dense and spacious, blending the arty excursions of Jane's Addiction, the bombastic riffage of Black Sabbath, and the offbeat time signatures of Rush. Throughout the disc, D'Amour's deep, booming bass lines keep the music brooding, and Keenan's vocals are passionate and confessional. On "Intolerance" he rails against his Southern Baptist upbringing, and in "Prison Sex" he addresses the sexual abuse he suffered as a child. Undertow isn't Tool's most musically accomplished album, but some consider it their most emotionally powerful.

|

|

KEENAN: We had just done Opiate and people seemed to be responding to it, and now it felt like we had to back it up and do something better, which was very tough. Back then we didn't have ProTools, so you didn't have the luxury of being able to do several takes and then go back and sort through the stuff. You had that two-inch tape, so you're constantly rewinding and you're on an emotional roll and you have to stop and start over all the time. The emotion might be captured on the tape, but the performance sucked. And then you might have an awesome performance but the emotion is null and void. So during that recording process, I really started to feel like, Oh. shit, this is no longer about the raw stuff. This is a different kind of thing.

CAREY: Working on Opiate with [producer] Sylvia Massey had gone so well we decided to use her again, and we also had the same assistant producer and engineer, so it was a real similar vibe. But because we had a little bit of success with Opiate, we didn't feel like we had to get in and out of the studio in

three days or we were gonna be broke, so we took about three weeks recording it. We had enough faith in the success that was gonna be coming to us that we decided to take a little bit longer, and it shows.

KEENAN: If we tried to pull some of the stuff" now that we did back then, we'd all be in jail or deported. We did this vivisection benefit at the Hollywood Palladium, and when we came out, we had these acoustic guitars and we started playing "Maynard's Dick" for this sold out crowd that wasn't there to see us at all. Then, right in the middle of the song, we all grabbed these five-dollar acoustic guitars we had bought in Tijuana. There was a whole stack of them by the side of the stage, and we just started smashing them and pulled out chainsaws and tore the hell out of these things. I had a shotgun with blanks in it, and I was shooting it inside the Palladium. Flames were leaping out of the barrel towards the curtain. Here arc all these horrified people there to save the bunnies and I'm singing, "Life feeds on life." They thought we were all

|

|

|

assholes. Of course, we were amused with ourselves and that's all that really mattered. We thought we were very clever...and still do.

JONES: When we first got approached by this girl to play that show, she was wearing leather Docs and talking about how killing animals was wrong. And we're like, Umm, you're wearing leather Docs. So we went the other way with it. Life feeding on life is very natural. And after we did this big thing, the same girl wearing leather Docs went, "Oh, that was sooo great," She totally missed the point. That performance was the birth of "Disgustipated," which is the industrial track at the end of Undertow. And when we did that, we bought two pianos for $100 a pop through [classifieds-only newspaper] The Recycler. The guy that ran Grand Master Studio has a huge indoor parking lot. We were like, "Hey, can we shoot shotguns at pianos and record it?" And he just goes,

|

Sure, just clean

up when you're

done." Since then, people

From other bands have come up to

us and gone, "Oh, man, we've seen

your shotgun holes in the wall."

CAREY: We put out Undertow and at first not that much happened. Then we went on the road with the Rollins Band, and every night we could tell we were winning over hundreds of new fans. After that tour ended, we were lucky enough to have a connection who got us on Lollapalooza, which at that time was the only tour of that Sort in the

world. We went from playing clubs to getting thrown on the main stage halfway through the tour. All of a sudden we were playing to 20,000 people a night. I had so much adrenaline, I'd count off the first song and then it would seem like I'd blink my eyes and i1 We got a lot of attention for that, so MTV played our video for "Sober" one time and they got bombarded with requests. We watched our record go from nowhere up to No. 50 on the charts, and it stayed there two years.

JONES: Contractually, the record label was supposed to talk to us about any sort of publicity stunt they pulled on our behalf especially with us paying for part of it. But without telling us, they made little kid T-shirts for the single "Prison Sex" with our Tool wrench logo on there, which is actually a phallic symbol. So the label was going to send the shirt to all the radio stations because Nirvana did that with one of their songs.

And we're going, "Well, first off, you didn't even talk to us about this." And they went. "No. you don't understand. Nirvana did this and it was a huge hit with radio." And Maynard goes, "Do you know what that song's about? It's about getting fucked in the ass as в little kid." They never shirts out.

KEENAN: The tragic part of that is they didn't get the joke they bat accidentally made. They're just that stupid. We had to say. "This is funny. I don't think you know it's funny, but it's funny and, no, we can't do that." But that song was a really tough one for me. There's not many things I regret having done, but doing those lyrics is one of them.

JONES: We did a video [with the late animator Fred Stuhr] for "Prison Sex." and while We were working on it at three in the morning the 1994 Northridge earthquake hit Los Angeles. We were on the

|

|

|

second floor when it hit, and before

I even knew it, Fred runs to the door

and stands in the doorway because

that's what you're supposed to do

in an earthquake. But the other five

of us who were there just ran out

and plowed over him and left him

lying on the ground. We jumped

over the stairs and onto the next

building, which was just one floor tall. I was scared shitless, because I knew that building would come down. It was. like, the worst thing that's ever happened to me and the best thing. When I looked out, I could see

downtown Hollywood and all the transformers were blowing. It looked like the city was being bombed. It was just so beautiful. And then I realized in my panic I had left my girlfriend sleeping in the other building. So I ran back and started

shouting her name, and just as I was calling for her, the quake stopped and I heard her. She couldn't climb from where she was because

the stairs had fallen and part of the building right next to us fell over, but she was OK.

KEENAN: I think some of the

growing pains really started to set

in when we were on the road for

Undertow, where you're starting

to figure each other out and figure

out what the nuances are, and the

hangups, and the emotional and mental obstacles. We started to

really see that the business is a

tough one to fucking navigate and get away from. I think we

went from zero to jaded in under

30 seconds. The honeymoon was

definitely over.

|

|

THE FIRST TOOL ALBUM RECORDED WITHOUT PAUL D'AMOUR

on bass, AEnima is texturally expansive and darkly psychedelic. In addition to passages that crash with the force of a head-on collision, there are numerous atmospheric parts that waft into the ether, oblivious to the violence that waits around the corner. Structurally, the music is looser than on Undertow, rarely adhering to the standard verse/chorus formula and relying on spacious jams as often as concrete riffs. New bassist Justin Chancellor brings an airier, more extemporaneous vibe to the band and, for the first time, the songs seem far more influenced by King Crimson than Black Sabbath. Several strange, industrial interludes make the nightmarish album even more surreal. "Intermission" is an upbeat merry-go-round organ ditty and "Die Eier von Satan" is a melange of grinding mechanical samples, harsh-sounding German declarations, and euphoric crowd cheers that sound like Einsturzende Neubauten playing a Nazi rally — until you realize that the angry German man is reading a recipe for Mexican wedding cookies. Such juxtaposition is the key to AEnima, especially in the lyrics, which are often more positive than the apocalyptic music suggests. While Keenan conjures a colossal earthquake to obliterate the superficiality of Los Angeles in the title track, he ponders the benefits of genetic mutation on "Forty-Six & 2" and discusses the mind-expanding qualities of psychedelics on the nearly 14-minute long "Third Eye," a foray into free-form exploration that laid the groundwork for Tool's future ventures.

|

|

CAREY: We toured for close to three years after Undertow came out, so by the time we started to work on AEnima, we had matured as functional musicians, and that changes your sound completely. Once you have that kind of freedom, an idea will come into your head and you can do it justice. But when you're not a good player you can have all the great ideas you want, but if you can't get them out, it doesn't matter. Before AEnima, we were just following our gut. There was a lot of anger in the air and we never tried to control that. But just as we mature as humans, with AEnima we tried to be fueled more by spiritual ideas or more of a conscious mode of aiming things in the right place or trying to take more responsibility for our art

KEENAN: AEnima was really hard at first. We spent a lot of time chasing our tails in that space, and things weren't happening with Paul D'Amour. Outside of that space it was great. We're friends, we talk, but in there it wasn't working and we had to part ways and let him do his own thing. God bless him. I think he was a victim of indie guilt. The band was getting bigger than he was comfortable with, and he was so much the "anti" guy that he wasn't allowing himself to enjoy the success. To save face, we told everybody that he quit, but he didn't. He was let go.

JUSTIN CHANCELLOR: I was living in London with my brother, and he was a friend of Matt Marshall, who signed Tool. So we were the first people over in Europe to get the first Tool demo in 1991, and me and my brother immediately cottoned on to it. When they put out Opiate, we took a trip to New York to see them play at CBGBs, and because we knew Matt, we were introduced to the band and became friends. And so in 1995 I did a gig in London with my band Peach, and as we were loading our amps out of the van back into the singer's flat, my flatmate called mc at the house and said I really had to call Adam in America. So I did, and he said Paul was gone and they really wanted me to try out. They sent me a demo of "Pushit," "AEnima," and "Eulogy," which were all in their infant stages, and had me learn them for the audition. Those were the first things we finished up after I joined, and from then it was on to new material, which was incredibly challenging and intimidating. First of all, I had just moved to America with only my guitar and clothes, which was very tough on a personal level. And then I went through a long period of time where I was trying to feel confident that the stuff I was coming up with and

|

|

sharing with them was good. They told me it was worthy and we should start working on it. but it was hard for me to believe them. All that I could think about was the stuff they had already done, which was a benchmark for me. I wasn't a confident person and it was very much a struggle to be in that situation. It was almost impossible for me to enjoy the experience, which was everything I ever wanted.

CAREY: All the people we tried out [including Kyuss' Scott Reeder and Filter's Frank Cavanaugh] were really good players but after we did the audition songs, we played a free-form jam, and when Justin did that with us, we instantly knew he was the right guy. Once we had a different personality there, everything completely changed - the whole dynamic, the chemistry that goes down in the room when we write — everything. There were even more possibilities because Justin's such a great musician and has so many vibrant ideas. It pushed us a whole new way.

KEENAN: For me, the first couple records were the primal scream. As a lyricist and performer, the idea was to work out some issues and then move the fuck on. So here you arc in your third year of telling the same story over and over again, which was a negative story to begin with and impacted your life in a negative way. And having to retell it every night is not so healthy. So, right around the time of AEnima I was trying to figure out a way to transmute that stuff and let it go-finding different paths to disintegrate that negativity. I did a lot of esoteric, spiritual, and religious research. I read a lot of mathematical and psychological books and just did a lot of introspection and a lot of "sound mind, sound body" studies. And that stuff helped take the record in a more esoteric, spiritual direction, but of course while still hanging on to some of the emotions and some of the charged feelings.

Дата добавления: 2015-10-23; просмотров: 81 | Нарушение авторских прав

| <== предыдущая страница | | | следующая страница ==> |

| Поведение в неформальных группах | | | WHEN THIS WRITER FIRST INTERVIEWED 2 страница |