Читайте также:

|

AEnima was then. Britney and N*Sync are now. Will Lateralus' heady fare be welcomed in today's" dumbed-down market?

"There is a worry that everyone's attention span has just gotten too short," responds Carey, whose calm demeanor recalls Jimmy Stewart. "There is a large percentage of people who are 'disgustipated' at the state of the music industry for whom Lateralus will be a breath of fresh air. I would like to say this will break down all the barriers and start a whole new revolution in music and show where the influence for a lot of the music of the last few years came from. But then, Trent Reznor's last album [1999's The Fragile] was the best thing he has ever done and it was the lowest selling. So it is scary. But we are a band believing the same thing and are completely convinced of it. There arc four beings here pushing as hard as they can trying to get the point across. There arc compromises that happen that make the songs so strong in the end. They can go to a larger total than the four parts would indicate."

|

Lateralus' song titles, such as "Mantra," "Parabola," "Ticks & Leeches," and "Faaip De Oaid" (meaning "The Voice of God") reflect the band's immersion in the occult, not to mention an unhealthy obsession with human disorders and primitive cures. But like atoms fusing in a nuclear reactor, the members of Tool knock up against each other in diverse ways to achieve their voodoo-laden heavy-metal magic. Keenan and Carey rule the occult sphere, while guitarist Jones guides the video and art direction of the band.

"It is like a marriage," notes Carey. "It is all about the communication. That is why the music will get stronger and stronger. As long as we communicate, the music will get more and more depth, emotionally and intellectually."

And like a good marriage, or perhaps like a broken one, weird things happen when Tool get together and jam in front of the massive Enochian magic board. Call it channeling the spirits, calling down the demons, or just getting loose in the third dimension with Masonic swords and The Book of Tbotb - Tool know how to make things happen.

"More and more often I have found that as we go on, the deeper our communication is with each other, the more often things just happen." Carey, an avid basketball player, bends down to rub his sore ankle. "The title track of this album was originally called '987.' It was a bass riff that Justin had; it is a bar of nine, a bar of -eight, and a bar of seven. We started talking about this, and Maynard said it had kind of a spiral-type feel, and we realized that 987 is the 16th step of the Fibonacci sequence, which is a mathematical sequence that all spirals follow, like conch shells and sunflowers. The song seemed to take on a higher power between us. It was just a matter of communication. Those arc the magical points; sometimes that is enough to build a whole song around."

A child of the occult in that his father, a full-fledged Mason, sometimes performed the esoteric rites in his presence, Carey readily acknowledges its pull on his psyche. One look at the drummer's bio at Toolband.com shows that Carey "performed a ritual utilizing his knowledge of the unicursal hexagram to generate a pattern of movement in space relating to [Buckminster] Fuller's vector equilibrium model. [He then] summoned a daemon he has contained within 'the Lodge' that has been delivering short parables similar to passages within [Aleister Crowley's] The Book of Lies." Is this info culled from some ancient mystery school? Pure Satanic evil? Or just organic knowledge lost to this so-called modem age?

"It's all definitely a source of my inspiration," says Carey. "It comes from researching, trying to find out about information that has been hidden for different reasons by religious factions. Most of it done unjustly. There could be valuable things

|

|

that might clue people into the answers they are looking for, but they are hidden for senseless reasons. It is still a curse today in the world of psychedelics. LSD could be like the telescope Galileo invented. But the government made it illegal to do research with it. Music and art and censorship do not go together. I disagree with censorship over anything. Do you notice there is never a war on coffee or television; it's always a war on drugs?"

The final track of Lateralus is one of the most visceral and horror inducing. As tormented beings, ani-

mals, somethings, seem to squirm and fry, a lone man rants about aliens and intruders while Carey pummels his drums with ferocious intent. It sounds like a case of ghosts in the machine, but Carey insists it's just another day on the job with Tool.

"That tune came about when I was recording really late one night and one of my old reverb units went haywire. It sounded like a transmission from beyond coming through, and I heard it reach its path to blowing up so I hit the record button on the DAT machine. You hear it going down the tubes. It had a compositional form to it. So I pushed it to the limit and developed it and made it as anxiety-laden and horrifying as possible."

But that raises a question. Surrounded by skulls, metaphysical symbols, occult books, and even an earthly demon that Carey admits to having summoned, is Tool's Hollywood studio a breeding ground, a possible passageway into a world of fallen angels and grief-stricken ghosts?

"Oh, I don't blow if they are ghosts." Carey delights in testing the waters and teasing the skeptical.

"But they, or something, shows up sometime in the most unexpected places. There is a sound in here that I hear all the time. The singer in Zaum [Carey's side project] used to call it 'The Dog, Molly, Scared.' It sounds like a whining dog. If you are in here for a day you will hear it. It has been here since I moved in. Everyone who has been in here has heard it. And when gear is malfunctioning and going nuts, you swear there is some demon haunting you or torturing you."

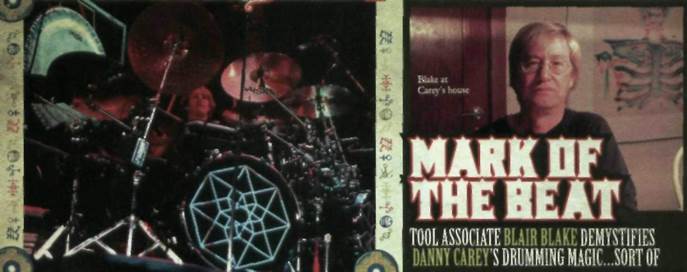

TOOL DRUMMER DANNY CAREY'S interest in the occult is no secret, as he has been frequently photographed with hexagrams, tarot decks, and other mystic signifiers around his drums. He shares his interest with his friend and Tool associate Blair Blake, who writes the band's newsletters. Care)' and Blake met in the mid-'8os and soon discovered the}' shared both a love of prog rock and an obsession with turn-of-the-century British occultist Aleister Crowley, a mystic who has fascinated rockers dating back to Led Zep and the Stones. In the mid-'90s, Blake helped set up Carey's drum set to align with occultist theories of "sacred geometry."

REVOLVER: What do you remember about setting up his drums?

BLAIR ВLAKE: We wanted to set it up proportionally to his body size. What we did back then was put a pentacle into six-sided geometry [a unicursal hexagram]. It's gone through different transformations over the years. He's a big guy. We wanted something that would fit with him and also something that correlated with his interests.

What are the symbols around his kit?

He has so many different drum kits right now, it's hard for me to keep up with it. But a lot of the boards and the symbols you will see are sigils [magical codes or seals]. The}' all have meaning to Danny. I don't know what some of them mean. He's learned how to do that and those are his little messages, but whether they're protective or talismanic, I'm not sure.

Has your interest in magic translated to music in any other ways?

Danny and I talked about the idea of taking star spectra and converting that into music. That's probably something more for a Danny solo record. [Laughs]

You are both Leister Crowley enthusiasts, too. right?

We're both collectors of his very rare first editions. And we've spent a lot of time doing that over the years.

In one of your newsletters you talk about tracking down a first edition of his book White Stains, which is rumored to have some of Crowley's semen on the cover.

I was saying something about cloning Crowley through that. Well, we never did anything with that, actually...at least as far as we want anyone to know. [Laughs] КORY GROW

|

|

|

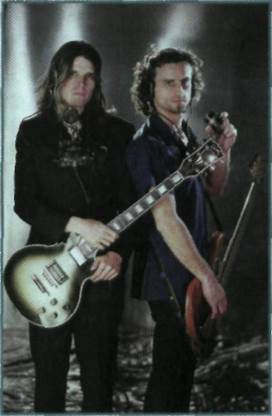

ADAM

ADAM

JONES

UNDER THE RECORD INDUSTRY'S standard

model for success, Tool should have been dead and

buried a long time ago. Whereas most bands "get

it while the getting is good," releasing albums and

touring to support them every year and a half or so

until the public loses interest. Tool disappear from the public eye

for excruciatingly long periods between albums and tours. Some

critics have even joked that their new album is titled 10.000

Days (Volcano/ZLG) because that's how long it took them to

make it — although 27-plus years is a bit of an exaggeration, even

by Tool's standards.

"Despite what everyone thinks, it didn't take us five years to make this record," says Tool guitarist Adam Jones. His point of reference is the group's previous album, 2001's Lateralus. "We took a long time off after the last tour." What's more, he adds, during that time singer Maynard James Keenan participated in

his numerous side projects, which include A Perfect Circle. "We started making this album a little more than a year ago."

While their record label would undoubtedly love it if Tool released a new album every two years or less, Jones believes the ample length of time between albums works to the band's advantage. "Our records don't sound like other people's records, where they release them a year apart and they end up sounding like a bad cover-band version of themselves," he says. "Each record sounds different from the one before it. Those long breaks we take give us time to absorb what's going on around us and grow. I think that shows on our records."

Tool have defied the record industry's penchant for overexposure. They maintain their mystery by not plastering their faces all over their album covers and videos, and by performing mostly in the shadows of the stage while overwhelming the audience's senses with stunning visuals and sound. Chances arc good that even the most devoted Tool fan would not recognize Keenan or Jones on the street. And the band prefers that listeners focus on the music rather than on the group's "image" or intimate details of its members' personal lives.

"1 get great emails from our fans," says Jones. "My favorite was from this girl who wrote to me on MySpace. She said, '1 finally figured it out: Lateralus was written to [2004 movie] The Passion of the Christ. It's so amazing how it links up. I want to thank you for doing that.' I wrote her back and said, 'Cool. You figured it out.' Of course we wrote that album way before The Passion of the Christ came out, but I loved how she tried to link our music to something else."

It's hard to imagine what influences Tool fans will hear on

10.000 Days. Expanding upon the ambitious approach of Lateralus, the new album features dizzying polyrhythmic lines and epic song structures in which ideas weave together or simply crash into one another. Its vast palette of sounds includes Talk Box and "radio" guitar solos from Jones, bassist Justin Chancellor's slithering fretless bass and off-kilter riffs, and Danny Carey's stunningly complex drum patterns, throbbing electronic noise, and funky Middle Eastern percussion. Keenan's vocals are often heavily processed with distortion or mixed down among the instruments so they're more like an instrument themselves.

10.000 Days. Expanding upon the ambitious approach of Lateralus, the new album features dizzying polyrhythmic lines and epic song structures in which ideas weave together or simply crash into one another. Its vast palette of sounds includes Talk Box and "radio" guitar solos from Jones, bassist Justin Chancellor's slithering fretless bass and off-kilter riffs, and Danny Carey's stunningly complex drum patterns, throbbing electronic noise, and funky Middle Eastern percussion. Keenan's vocals are often heavily processed with distortion or mixed down among the instruments so they're more like an instrument themselves.

"This record sounds so huge," says Jones. "That's because the vocals aren't mixed way out front. When you mix the vocals out front, it crushes the force of the band behind them."

Whereas Tool's last two albums were produced by David Bottrill (Peter Gabriel, King Crimson), this time the band chose to produce 10,000 Days itself, enlisting Joe Barresi (Melvins, Queens of the Stone Age, Bad Religion) to engineer and mix the album. Jones notes that although other people may have previously received production credit, the band has actually produced itself from the beginning.

"Every time we've made a record, our songs were already worked out by the time we started recording," says Jones. "But every time we've worked with someone, they've wanted a production credit. We'd say, 'OK. Why not?' But to me a producer is someone who comes in when you don't have your songs worked out or you want to be a certain kind of band and you need someone to come in and make you into that type of band. It reminds me Of American Idol — or as I call it, The Gong Show Rip-Off."

Although rumors of Tool's breakup regularly surface-fueled largely by Keenan's tendency to become immersed in side projects during the band's downtime-Jones insists that the relationship between the four members has never been stronger. Absence, it turns out, may not only make the heart grow fonder but may also be the key to enjoying a long, successful career as a band.

"I'm really lucky that the three other guys I work with are so

incredible," Jones says. "It's not perfect; we don't all see eye to eye. We fight, not with our fists, but we disagree or get into arguments when one person wants to go in a certain direction and the others don't. But we all respect each other and try to work it out. It's a four-way arrangement. We split everything four ways. I think that's why we've been together as long as we have."

REVOLVER: The songs on 10,000 Days are structured more like classical music: They start in one place, go somewhere else, and end in a completely different place altogether. It's as if the songs are telling a story in a linear fashion.

ADAM JONES: Thanks. That's the thinking. This is going to sound really pretentious, but it's more emotional. For us, writing music is very therapeutic. You get to these different states, and it's almost like you're entertaining yourself. You're leading someone by the hand, but the hand you're leading is your own. I don't get choked up when I hear other people's music, except in a few rare instances. The Melvins did something that I thought was absolutely fuckin' beautiful. But if we write something I really like, I get tear}' eyed. I'm the kind of guy who can cry really easily. The really long song on the record that starts very classically and builds is my favorite song that we have ever done. I get really choked up whenever we play it. I was really worried where Maynard was going to go with it, but he nailed the lyrics on that one.

That song is quite a tour de force. You really don't notice how long it is while you're listening to it.

I'm 41, and I never thought about that stuff as a kid. I never bought a record and thought. Oh, this song is

long. I never thought "Stairway to Heaven" was a long song. I loved how there was this part and then there was another part that was completely different. If you're making music for all the right reasons, people are going to be receptive to that and appreciate it the same way you did when you were writing it. It's not radio friendly, but we're not...

What specifically influenced you while you were making this album?

I got into studying polyrhythms and experimental math, seeing what different kinds of math worked together. If they didn't work, I'd try to figure out why and determine what I had to throw in to make them work. I listened to a lot of classical and electronic music as well as a lot of metal, especially the heavier stuff. I tried to get into as many paths as I could.

You can hear a lot of polyrhythms. not only within how you. Justin, and Danny played together but also within your own playing. You can especially hear that in some of your tremolo and delay effects, where the tempos seem to change freely yet remain in sync. How did you do that?

I had some custom pedals made. Our engineer on this album, Joe Barresi. is a pedal god, and he knows everyone. I used a Gig-FX Chopper pedal, which has a nice tremolo. We had them work on the pedal so I could go from a clean sound to tremolo and control the tremolo speed as well. The pedal. lets me slow it down and speed it up, which really lends a lot of power for creating motion when we're going from one part to another. I told Joe that I wished I could do this with any pedal. He came back with this thing that looked like a wah pedal, but you plug other pedals into it; it blends between your clean sound and the pedal effect, so you can fade the effect in gradual!)', like a breath, instead of just clicking the pedal on.

You also played a Talk Box solo.

I always wanted to use a Talk Box - I love Joe Walsh [Eagles guitarist who famously used a Talk Box on his solo hit "Rocky Mountain Way"]-but I never wanted to use it for the sake of using it. We wrote this song and I knew that it was the song where the Talk Box would work really well. Joe Barresi knew [Heil Talk Box inventor] Bob Heil and contacted him. He was just awesome. He gave

|

me free stuff, told me what mics worked best, and showed me how to get the best sound.

me free stuff, told me what mics worked best, and showed me how to get the best sound.

The polyrhythms, arpeggiated patterns, and mathematical aspects suggest the influence of King Crimson.

There's a little bit of that. [King Crimson founding guitarist Robert] Fripp showed me some stuff. So did [King Crimson/Mr. Mister drummer] Pat Mastelotto and [King Crimson multi-instrumentalist] Trey Gunn. Those guys are giants, and it was great to learn from them. I've also learned a lot from Meshuggah. They're not so much about polyrhythms as they are about trying different things together and seeing where the)' meet. The}' may play in three, then in five, then in four in one progression of riffs; if the drummer is playing over that in four, they'll see where the rhythms meet up. It's so exciting. Meshuggah are modern prog-rock as far as I'm concerned. That influence is also on this record.

Are you still using your Marshall and Diezel amps? Have you made any significant changes to your equipment rig?

1 don't know yet. After hooking up with Joe Barresi, I became really impressed with Bogner amps. I was also impressed with this Rivera amp and a Peavey amp that Joe had. I would never think to play a Peavey amp, but it's awesome. Joe calls it his "Mississippi Marshall," but if I was to play live right now I would play my Marshall and two Diezels through my Mesa/Boogie cabinets, which are amazing. There's nothing like them. They really put out that low end.

It sounds like you're playing an E-Bow on one song…

Please don't say that I play an E-Bow. They say on their website that I use one, but I don't. If I used one, I'd say it, but I don't. I asked Robert Fripp what is the best way to get sustain — meaning what equipment should I use, what strings, what kind of amp. He said, "Attitude." And he's right. If you play that note and you want sustain out of it, you'll get sustain. J have overdrive pedals, a wah, and my amp. I have one of those blue Coloursound fuzz pedals and a Foxx Tone Machine, which they just reissued. Those are great for sustaining notes. I've realty tried to get a note to hold as long as it can and make it sing or make it bend on its own.

Дата добавления: 2015-10-23; просмотров: 61 | Нарушение авторских прав

| <== предыдущая страница | | | следующая страница ==> |

| WHEN THIS WRITER FIRST INTERVIEWED 5 страница | | | JUSTIN CHANCELLOR |