Читайте также:

|

1. The model of parts of the sentence.

2. The distributional model. The model of immediate constituents

(IC-model).

3. The transformational model (TM).

1. In order to state general rules of sentence construction it is necessary to refer to smaller units. The process of analyzing sentences into their parts, or constituents, is known as parsing.

The syntactic structure of the sentence can be analyzed at two levels:

pre-functional (constituents are words and word-groups) and functional (constituents are parts of the sentence).

Parts of the sentence are notional sentence constituents, which are in certain syntactic relations to other constituents or to the sentence as a whole. Accordingly we distinguish between principal parts of the sentence, constituting the predication, or the basic structure of the sentence, and secondary parts of the sentence, extending, or expanding the basic structure.

Parts of the sentence are notional constituents as they name elements of events, or situations denoted by the sentence; actions or states, different participants and circumstances. The formal properties of parts of the sentence are the type of syntactic relations and the morphological expression.

Principal parts of the sentence are interdependent. The subject is the structural centre of the sentence — the predicate agrees with the subject in person and number. The predicate is the semantic and communicative centre of the sentence.

Secondary parts of the sentence are modifiers of principal and other

secondary parts: attributes are noun-adjuncts, objects and adverbial modifiers are primarily verb-adjuncts,

Structurally parts of the sentence may be of three types: simple, expressed by words and phrases; compound, consisting of the structural and notional part (compound verbal and nominal predicate, subject with the introductory it and there; complex, expressed by secondary predications (typical of secondary parts of the sentence).

As there is no direct correspondence between units of different levels of

sentence structure and as grammatical phenomena have fuzzy (not distinct) boundaries which often overlap, there are difficulties in distinguishing between certain parts of the sentence:

(1) I want to leave (object or part of the predicate?)

(2) Features of her mother and father were blended i n her face (adverbial modifier or prepositional object?)

(3) He was happy to see me (object or part of the predicate?)

(4) A cup of tea (object or attribute?)

Besides the three traditional secondary parts, two more are singled out: the apposition and the objective predicative. (They painted the door green). Objective predicative is co-referential with the object, subjective predicative is co-referential with the subject (The door is green). Both types are denoted by the term complement. This term may be also used to denote all verb-adjuncts.

So the model of parts of the sentence shows the basic relations of notional sentence constituents. It does not, however, show the linear order of constituents. The order of constituents is shown by two models of analysis worked out by the American school of structural (descriptive) linguistics: the distributional model and the model of immediate constituents (I C-model). These models analyze the sentence structure at the pre-functional level.

2. Methods of structural linguistics are based on the notions of position, co-occurrence and substitution (substitutability).

Position, or environment is the immediate neighbourhood of the element.

Co-occurence means that words of one class permit or require the occurrence of words of another class.

The total set of environments of a certain element is its distribution. The term distribution denotes the occurrence of an element relative to other elements.

The distributional model, worked out by Ch. Fries (“The Structure of English”), shows the linear order of sentence constituents (see Topic XI). The syntactic structure of the sentence is presented as a sequence of positional classes of words:

The old man saw a black dog there.

1) D A1 N1 V D A2 N2 Adv

2) D 3a 1a 2 D 3b 1 b 4

Showing the linear order of classes of words (their forms may also be indicated), the model does not show the syntactic relations of sentence constituents. The sentence I saw a man with a telescope is ambiguous, but the ambiguity cannot be shown by the distributional model. This drawback is overcome by the IC-model.

A sentence is not a mere sequence, or string of words, but a structured string of words, grouped into phrases. So sentence constituents are words and word-groups. The basic principle for grouping words into phrases (endo- or exocentric) is cohesion, or the possibility to substitute one word for the whole group without destroying the sentence structure. Applying the substitution test, (or the dropping test, dropping optional elements) we define syntactic relations and can reduce word-groups to words and longer sentences to basic structures:

(1) NP—N poor John — John

The phrase is endocentric, the adjunct poor is optional, the. head -word John is obligatory.

(2) The old man saw a black dog there.

Word-groups are reduced to head-words and the sentence is reduced to the basic structure, directly built by two immediate constituents — NP and VP.

When we know the rules of reducing the sentence to the basic elementary structure, it is not difficult to state the rules of extending/expanding elementary sentences:

S—NP + VP

NP—A + N

VP—V + D (Adv)

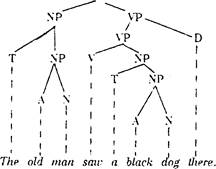

So the sentence is built by two immediate constituents (NP+VP), each of which may have constituents of its own. Constituents, which cannot be further divided, are called ultimate (UC). The IC-model existsin two main versions: the analytical model and the derivation tree. The analytical model divides the sentence into IC-s and UC-s:

The derivation tree shows the syntactic dependence of sentence constituents:

S

The sentence:

I saw a man with a telescope

will have 2 IC-structures:

(I) Prn V T N Prp T N

(2) Prn V T N Prp T N

So the IC-model shows both the syntactic relations and the linear order of elements.

But the IC-model cannot sometimes show that the relations between the elements of the two sentences are different, e.g.:

John is easy to please.

John is eager to please.

The sentences have the same derivation tree showing the IC of the sentences. Only the transformations of the two sentences can show the relations of their elements, that is that John is the subject of please in is eager to please but the object in is easy to please. The conclusion is that we must teach the IC-model as a means of producing kernel sentences.

3. Kernel sentences are sentences, in which all constituents are obligatory. They are also called basic structures, or elementary sentences. We must keep in mind that kernel sentences are not many in number. Linguists (Harris) single out from 2 to 7 kernel sentences: 1) NV 2) NVN 3) NVPrepN 4) N is N 5) N is A 6) N is Adv. 7) N is PrepN.

Khaimovich and Rogovskaya consider the heading “basic patterns” to be rather pretentious as the list does not include sentences with zero predications or with partially implied predivativity while it displays the combinability of certain classes.

S. Porter reduces the number of kernel sentences to three: “All simple sentences belong to three types:

A. The sun warms the earth.

B. The sun is a star.

C. The sun is bright.

The structure of all other sentences may be explained as a result of transformations of kernel structures. This analysis, showing derivational relations of sentences, is called transformational. TM is based on IC-model and it goes further showing semantic and syntactic relations of different sentence types.

TM was first discussed by the outstanding American linguist N. Chomsky, and it greatly influenced further development of linguistics, other models either developing TM or being reactions to TM. In the course of the development of the model the focus of attention shifted from syntax to semantics.

TM descries paradigmatic relations of basic and derived structures, or the relations of syntactic derivation. Kernel sentences, which serve as the base for deriving other structures, are called deep or underlying structures opposed to surface structures of derived sentence types, or transforms. So both the deep and the surface structure belong to the syntactic level of analysis.

A kernel sentence structure gives out a number of derived transforms:

S – NP S – S

The work of the machine The machine does work.

The machine’s work Does the machine work?

The machine work What works?

The working machine The machine does not work.

For the machine to work The machine did not work.

The machine’s working etc.

The machine working

The machine works.

S1 + S2 – S3

The machine works and hums.

When the machine works it hums.

Working, the machine hums.

When working the machine hums.

I like when the machine works.

If the machine worked, etc.

Transformations may be subdivided into intra-model, or single-base (changing the kernel structure) and two-base (combining 2 structures).

Single-base transformations may be of two types: modifying the kernel structure and changing the kernel structure:

(1) She is working hard. — She is not working hard.

(2) She is working hard. — Her working hard— Her hard work.

The study of the transformational rules will come to the student in 3 steps indicated by Harris. First one must study transformations in simple sentences, then the two-base transformations (compound, semi-compound, complex, semi-complex sentences) and the transformation of nominalization.

The transformations of the simple sentences can be divided into two types: obligatory and optional.

Obligatory transformations are transformations on the morphemic level that intra-model transforms within one and the same model. The involve the following changes of the finite verb:

1) the choice of the tense;

2) the choice of number and person;

3) the choice of modality;

4) the choice of aspect.

Optional transformations are transformations on the syntactic level. An optional transformation may be chosen by the speaker depending on the purpose of communication (question, command, exclamation).

Transformation of nominalization:

The seagull shrieked. The shrieking of the seagull

He loves pictures. His love for pictures

Дата добавления: 2015-10-26; просмотров: 155 | Нарушение авторских прав

| <== предыдущая страница | | | следующая страница ==> |

| The Category of Voice | | | Возможные перемещения и возможные скорости |