Читайте также:

|

1. Михайловский дворец был построен по проекту знаменитого архитектора Карло Росси.

2. Здание дворца было возведено между 1819 и 1825 гг.

3. В 1895 году император Александр III приказал открыть музей в Михайловском дворце.

4. В 1898 году Михайловский дворец был превращен в Музей Русского Искусства.

5. Сейчас в Русском Музее мы можем увидеть работы лучших русских художников.

6. В 1957 году перед музеем был торжественно открыт памятник великому русскому поэту Александру Пушкину.

Unknuwn Artist.Emperor Alfxtmilrr III. I8SO- 1890. Si Mirliafl's Casrle

Ernst Liphart.

Enijii'mr Nirlm/as II. 19 11. St Mirlun-rx Caxlle

Ceremonial Openingof the Alexander IIIRussian Museumon March 7th 1S9S.Members nf thr Academy t>f Arts

Ceremonial Openingof the Alexander IIIRussian Museumon March 7th 1S9S.Members nf thr Academy t>f Arts

The Mikhailtntsky Palace. Halls of the Russian Museum

The Mikhailtntsky Palace. Halls of the Russian Museum

The Alexander III Russian Museum Attendants'

Uniform. 1898

The Alexander III Russian Museum Attendants'

Uniform. 1898

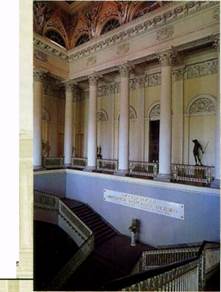

The Main Vestibule.The Mikhailoi'sky Palace. 1900

Hall No. II (mm-No. 37).

18th Century Portrait.*. 1910s

The Main Vestibule.The Mikhailoi'sky Palace. 1900

Hall No. II (mm-No. 37).

18th Century Portrait.*. 1910s

Hall No. XXIII (huh' No. 16). Knil lintllot'. 1920

Hall No. XXIII (huh' No. 16). Knil lintllot'. 1920

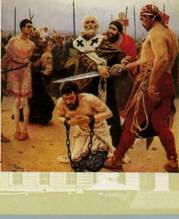

llya Reptn.

Nicholas Mirlikiisky Deliwring

Three Men Unjustly Sentenced

Ta Death. 1888

llya Reptn.

Nicholas Mirlikiisky Deliwring

Three Men Unjustly Sentenced

Ta Death. 1888

HaUNo. XXVI (mm'No. 12). Ivan Kramskoi, Murk Antiilinl.\kif. 1920

HaUNo. XXVI (mm'No. 12). Ivan Kramskoi, Murk Antiilinl.\kif. 1920

The Main Vestibule, The Mikhaihiasky Palm

The Main Vestibule, The Mikhaihiasky Palm

| The idea for the creation of a national public Russian Museum, in which the fine arts would occupy a central place, had been first muted amongst educated sections of Russian society long before Nicholas's decree. The 1812 campaign against Napoleon, which became known in Russia as the Patriotic War, led to a natural upsurge of patriotic fervour and renewed interest in the history of Russian culture and the sources and paths of its development. The “Syn Otechestva” (Son of the Fatherland) journal printed Fyodor Adelung's article "Proposal For Establishing A Russian National Museum" (1817) and Burhard Wichmann's"A Russian National Museum" (1821). In 1824 Vasily Grigorovich, later conference secretary of the Academy of Arts, compiled a "Report on the Desirability of Forming a Special Department of Works by Russian Artists in the Hermitage". Such a gallery of Russian works of art was subsequently collected from the Imperial palaces of Moscow and St. Petersburg and opened in 1825. The XIX century in Russia saw the birth of a new craze for collecting works of art. The "social portrait" of collectors and collections also changed. Alongside the old ancestral collections, gathering dust in country estates and passed down from generation to generation, new collections began to appear. These new collections were put together by people from various classes of Russian society, amongst them the intelligentsia, the merchant class and raznochintsi. Such collections often disintegrated just as quickly as they were first put together. And yet whilst for some buying works of art was nothing more than a fashionable diversion, for others serious collecting became their main pastime and purpose in life. In the first half of the XIX century, the overwhelming majority of collections were concentrated in the capital, St. Petersburg. Besides the Russian Gallery in the Hermitage and the museum of the Academy of Arts (in existence since the XVIII century yet pursuing primarily academic aims), the collections of Alexcei Tomilov (1779-1848), Pavel Svinin (1787- 1839), Nikolai Bykov (1812-1884) and the gallery of Fyodor Pryanishnikov (1793-1867) are all worthy of mention. Pryanishnikov's collection was acquired by the state in 1867 and transferred to the Moscow Public Museum, also home to the Petersburg collection of Count Nikolai Rumyantsev (1752-1826) since 1861. This move symbolically reflected the relocation of the center of collecting in the mid-nineteenth century to Moscow, where art life had always been more vigorous and democratic. Amongst prominent Muscovite collections were those of the palace book-keeper and head of a family of painters Yegor Makovsky (1802-1886), the architect Yevgraf Tyiirin (1792-1870) and the merchants, Kozma Soldatenkov (1818-1901) and Dmitry Botkin (1829-1889). At the same time the accent on the “museum factor" - a collection's diversity and public accessibility - intensified amongst collectors. The wine merchant. Vastly Kokerev (1817-1889) had a special building built to house his short-lived gallery. More lasting was the collection of the hereditary merchant Pavel Trelyakov (1|832-1898). His intention was to make his collection fully accessible to the public and it eventually grew into the country's largest museum of Russian art. Towards the end of the century, however, there were still no private museums in St. Petersburg or Moscow large enough to offer a complete picture of the history of art in Russia, right up to its most recent period - the 1860s-1880s, the heyday of the peredvizhniki. What was needed was a state museum. "The organization of an exclusively Russian public picture gallery would undoubtedly be highly desirable here in Russia... Construction of a new museum is vital to the history of our national art” were the words of a report made by Alexander Vasilchikov, director of the Hermitage, dated October 8th 1881. "We still do not have a national museum and it is high time we did," Vladimir Stasov (1824-1906) wrote in 1882, "... and not only because the capitals of all other European nations boast national museums (and not for all that long, either)... No, there is a much more important reason. Because our very own national school of art has finally come into its own... No matter how fine and outstanding the initiative of all the Pryanishnikovs, Trelyakovs and Soldatenkovs, this task should not be left to such noble and magnanimous volunteers alone... The state itself must create first one, and then several, centres where works of national art can be assembled, where they can flow as one mighty wave and where the whole nation will always he able to find them, its most precious property." The historical specifics of the situation were in that the idea was "stirred" by the coinciding of the national patriot aspirations of both liberal society and Emperor Alexander III, who - as was officially cultivated - was said to be a connoisseur and patron of Russian art. Alexander's acquisition in 1889 of Repin's picture Nicholas Mirlikiisky Delivering Three Men Unjustly Sentenced To Death from the 17th Exhibition of the Society of Travelling Art Exhibitions was thus regarded as expression of the intention "to found a national public museum, in which all the best works of Russian art would be concentrated." Regardless of the political angle, there was an undoubted need to create a stale museum in the capital, to fill the space that had been left between the biased private collections and the equally biased "departmental museums". The failings of the former were witnessed in the long drawn-out crisis that afflicted the board of the Tretvakov Gallery. The problem arose when its owner, in his twilight years, attempted to unite unsuitable motives when writing his will and only ended up contradicting himself. On the one hand he desired to leave his collection intact and immutable after his death. On the other he wished to see his gallery become a living, developing and growing museum. The shortcomings of the departmental institutions could be seen in the caste secrecy and "academical-educational" aspirations of the museum of the Academy of Arts, ignoring both the interests of the public and the possibilities for non-Academic paths in the history of art. It was hoped that a non-departmental state establishment would avoid these extremities, actively participating in both the historical aspect and the modern art process. This was what the Emperor Alexander III Russian Museum was subsequently proposed to become, and for which a fitting building was so successfully found that unique monument to early XIXth century Classical Russian architecture, the Mikhailovsky Palace. |

Дата добавления: 2015-10-26; просмотров: 112 | Нарушение авторских прав

| <== предыдущая страница | | | следующая страница ==> |

| МИХАЙЛОВСКИЙ ДВОРЕЦ (РУССКИЙ МУЗЕЙ). | | | Ex. 4a) Match the definitions with the terms they define. Find their Russians equivalents. |