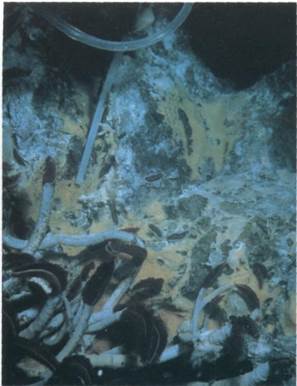

Various sulfur compounds can be oxidized by chemolithotrophs to meet their energy needs. The chemolithotrophic activities of sulfur-oxidizing microorganisms received considerable attention when it was found that a highly productive submarine area off the Galapagos Islands is supported by the productivity of chemolithotrophs growing on reduced sulfur released from thermal vents in the ocean floor (FIG. 6-28). It is unusual to find an ecological system driven by chemolithotrophic metabolism. Some sulfur-oxidizing chemolithotrophic bacteria, such as Thiobacillus thiooxidans, can oxidize large amounts of reduced sulfur compounds with the formation of sulfate. The sulfur-oxidizing activities of this bacterium are detrimental in nature because they result in the formation of acid mine drainage; however, they are beneficial for mineral recovery processes and are used for the recovery of copper and uranium, as well.

184 CHAPTER 6 CELLULAR METABOLISM

FIG. 6-28 The tube worms (Riftia pachyptila) that grow extensively near deep sea thermal vents have no gut. They have extensive internal populations of sulfur-oxidizing chemolithotrophic bacteria that produce the nutrients used by these animals for sustenance. The red-brown color of the worms is due to a form of hemoglobin that supplies oxygen and hydrogen sulfide to the chemolithotrophic bacteria within the tissues of the tube worms. Microbial mats of Beggiatoa grow between strands of the tube worms at the Guaymas Basin vent site (Gulf of California) at a depth of 2,010 meters.

Nitrification

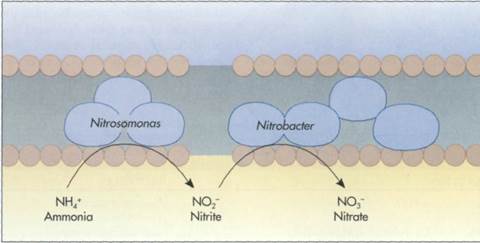

Nitrifying bacteria oxidize either ammonium or nitrite ions. Bacteria, such as Nitrosomonas, oxidize ammonia to nitrite (FIG. 6-29). Other bacteria, such I as Nitrobacter, oxidize nitrite to nitrate. Because the chemolithotrophic oxidation of reduced nitrogen j compounds yields relatively little energy, chemo- ; lithotrophic bacteria carry out extensive transforma- I tions of nitrogen in soil and aquatic habitats to syn- I thesize their required ATP. The activities of these bacteria are important in soil because the alteration of the oxidation state radically changes the I mobility of these nitrogen compounds in the soil col- I umn. Nitrifying bacteria lead to decreased soil fertility because positively charged ammonium ions bind to negatively charged soil clay particles, whereas the negatively charged nitrite and nitrate ions do not bind and are therefore leached from soils by rain- I water.

Nitrogen Fixation

The evolution of a mechanism for converting atmos- j pheric nitrogen into reduced nitrogen compounds such as ammonia was a major event in the progress and development of cellular metabolism. It is this I process, called nitrogen fixation, that makes nitro- I gen available for incorporation into proteins. This is critical because, while carbohydrates and lipids can I be synthesized from photosynthetic products based on C02 fixation, proteins and nucleic acids cannot be synthesized, because they contain nitrogen. Therefore life could not have persisted and expanded in the early oceans unless a means of replacing organic nitrogen compounds evolved. The process of nitro-

FIG. 6-29 Nitrifying bacteria are chemolithotrophs that oxidize inorganic nitrogen compounds to generate ATP. Some, such as Nitrosomonas, oxidize ammonium ions (NH4+) to nitrite ions (N02~) (left); others, such as Nitrobacter, oxidize nitrite ions to nitrate ions (N03~) (right). These reactions take place within specialized membranes that intrude within the cytoplasm of nitrifying bacteria.

Дата добавления: 2015-10-30; просмотров: 124 | Нарушение авторских прав

| <== предыдущая страница | | | следующая страница ==> |

| Photosystems and ATP Generation | | | METABOLIC PATHWAYS 185 |