|

Читайте также: |

THROTTLE

A Tale Inspired by “Duel”

Joe Hill and Stephen King

Contents

Cover

Title page

Throttle

About the Authors

Credits

Copyright

More from the Authors

About the Publisher

Throttle

THEY RODE WEST FROM THE SLAUGHTER, through the painted desert, and did not stop until they were a hundred miles away. Finally, in the early afternoon, they turned in at a diner with a white stucco exterior and pumps on concrete islands out front. The overlapping thunder of their engines shook the plate-glass windows as they rolled by. They drew up together among parked long-haul trucks, on the west side of the building, and there they put down their kickstands and turned off their bikes.

Race Adamson had led them the whole way, his Harley running sometimes as much as a quarter-mile ahead of anyone else’s. It had been Race’s habit to ride out in front ever since he had returned to them, after two years in the sand. He ran so far in front it often seemed he was daring the rest of them to try and keep up, or maybe had a mind to simply leave them behind. He hadn’t wanted to stop here but Vince had forced him to. As the diner came into sight, Vince had throttled after Race, blown past him, and then shot his hand left in a gesture The Tribe knew well: follow me off the highway. The Tribe let Vince’s hand gesture call it, as they always did. Another thing for Race to dislike about him, probably. The kid had a pocketful of them.

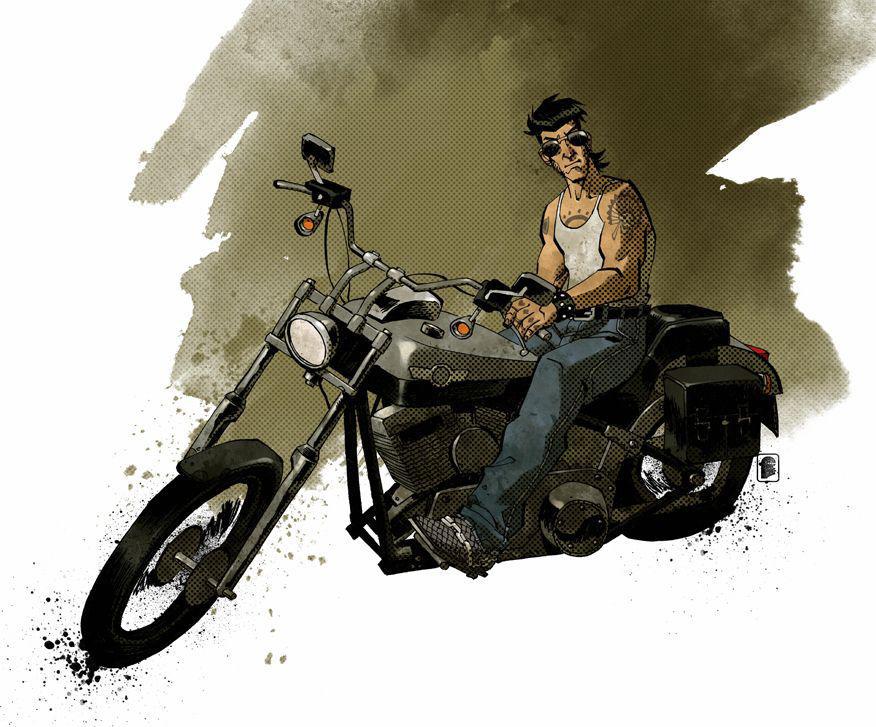

Race was one of the first to park but the last to dismount. He stood astride his bike, slowly stripping off his leather riding gloves, glaring at the others from behind his mirrored sunglasses.

“You ought to have a talk with your boy,” Lemmy Chapman said to Vince. Lemmy nodded in Race’s direction.

“Not here,” Vince said. It could wait until they were back in Vegas. He wanted to put the road behind him. He wanted to lie down in the dark for a while, wanted some time to allow the sick knot in his stomach to abate. Maybe most of all, he wanted to shower. He hadn’t gotten any blood on him, but felt contaminated all the same, and wouldn’t be at ease in his own skin until he had washed the morning’s stink off.

He took a step in the direction of the diner, but Lemmy caught his arm before he could go any farther. “Yes. Here.”

Vince looked at the hand on his arm—Lemmy didn’t let go; Lemmy of all the men had no fear of him—then glanced toward the kid, who wasn’t really a kid at all anymore and hadn’t been for years. Race was opening the hardcase over his back tire, fishing through his gear for something.

“What’s to talk about? Clarke’s gone. So’s the money. There’s nothing left to do. Not this morning.”

“You ought to find out if Race feels the same way. You been assuming the two of you are on the same page even though these days he spends forty minutes of every hour pissed off at you. Tell you something else, boss. Race brought some of these guys in, and he got a lot of them fired up, talking about how rich they were all going to get on his deal with Clarke. He might not be the only one who needs to hear what’s next.” He glanced meaningfully at the other men. Vince noticed for the first time that they weren’t drifting on toward the diner, but hanging around by their bikes, casting looks toward him and Race both. Waiting for something to come to pass.

Vince didn’t want to talk. The thought of talk drained him. Lately, conversation with Race was like throwing a medicine ball back and forth, a lot of wearying effort, and he didn’t feel up to it, not with what they were driving away from.

He went anyway, because Lemmy was almost always right when it came to Tribe preservation. Lemmy had been riding six to Vince’s twelve going back to when they had met in the Mekong Delta and the whole world was dinky dau. They had been on the lookout for trip wires and buried mines then. Nothing much had changed in the almost forty years since.

Vince left his bike and crossed to Race, who stood between his Harley and a parked truck, an oil hauler. Race had found what he was looking for in the hardcase on the back of his bike, a flask sloshing with what looked like tea and wasn’t. He drank earlier and earlier, something else Vince didn’t like. Race had a pull, wiped his mouth, held it out to Vince. Vince shook his head.

“Tell me,” Vince said.

“If we pick up Route 6,” Race said, “we could be down in Show Low in three hours. Assuming that pussy rice-burner of yours can keep up.”

“What’s in Show Low?”

“Clarke’s sister.”

“Why would we want to see her?”

“For the money. Case you hadn’t noticed, we just got fucked out of sixty grand.”

“And you think his sister will have it.”

“Place to start.”

“Let’s talk about it back in Vegas. Look at our options there.”

“How about we look at ’em now? You see Clarke hanging up the phone when we walked in? I heard a snatch of what he was saying through the door. I think he tried to get his sister, and when he didn’t, he left a message with someone who knows her. Now why do you think he felt a pressing need to reach out and touch that toe-rag as soon as he saw all of us in the driveway?”

To say his goodbyes was Vince’s theory, but he didn’t tell Race that. “She doesn’t have anything to do with this, does she? What’s she do? She make crank too?”

“No. She’s a whore.”

“Jesus. What a family.”

“Look who’s talking,” Race said.

“What’s that mean?” Vince asked. It wasn’t the line that bothered him, with its implied insult, so much as Race’s mirrored sunglasses, which showed a reflection of Vince himself, sunburnt and a beard full gray, looking puckered, lined, and old.

Race stared down the shimmering road again and when he spoke he didn’t answer the question. “Sixty grand, up in smoke, and you can just shrug it off.”

“I didn’t shrug anything off. That’s what happened. Up in smoke.”

Race and Dean Clarke had met in Fallujah—or maybe it had been Tikrit. Clarke, a medic specializing in pain management, his treatment of choice being primo dope accompanied by generous helpings of Wyclef Jean. Race’s specialties had been driving Humvees and not getting shot. The two of them had remained friends back in The World, and Clarke had come to Race a half a year ago with the idea of setting up a meth lab in Smith Lake. He figured sixty grand would get him started, and that he’d be making more than that per month in no time.

“True glass,” that had been Clarke’s pitch. “None of that cheap green shit, just true glass.” Then he’d raised his hand above his head, indicating a monster stack of cash. “Sky’s the limit, yo?”

Yo. Vince thought now he should have pulled out the minute he heard that come out of Clarke’s mouth. The very second.

But he hadn’t. He’d even helped Race out with twenty grand of his own money, in spite of his doubts. Clarke was a slacker-looking guy who bore a passing resemblance to Kurt Cobain: long blond hair and layered shirts. He said yo, he called everyone man, he talked about how drugs broke through the oppressive power of the overmind. Whatever that meant. He surprised and charmed Race with intellectual gifts: plays by Sartre, mix tapes featuring spoken-word poetry and reggae dub.

Vince didn’t resent Clarke for being an egghead full of spiritual-revolution talk that came out in some bullshit half-breed language, part Pansy and part Ebonics. What disconcerted Vince was that when they met, Clarke already had a stinking case of meth mouth, his teeth falling out and his gums spotted. Vince didn’t mind making money off the shit but had a knee-jerk distrust of anyone gamy enough to use it.

And still he put up money, had wanted something to work out for Race, especially after the way he had been run out of the army. And for a while, when Race and Clarke were hammering out the details, Vince had even half-talked himself into believing it might pay off. Race seemed, briefly, to have an air of almost cocky self-assurance, had even bought a car for his girlfriend, a used Mustang, anticipating the big return on his investment.

Only the meth lab caught fire, yo? And the whole thing burned to a shell in the space of ten minutes, the very first day of operation. The wetbacks who worked inside escaped out the windows and were standing around, burnt and sooty, when the fire trucks arrived. Now most of them were in county lockup.

Race had learned about the fire, not from Clarke, but from Bobby Stone, another friend of his from Iraq, who had driven out to Smith Lake to buy ten grand worth of the mythical true glass, but who turned around when he saw the smoke and the flashing lights. Race had tried to raise Clarke on the phone, but couldn’t get him, not that afternoon, not in the evening. By eleven, The Tribe was on the highway, headed east to find him.

They had caught Dean Clarke at his cabin in the hills, packing to go. He told them he had been just about to leave to come see Race, tell him what happened, work out a new plan. He said he was going to pay them all back. He said the money was gone now, but there were possibilities, there were contingency plans. He said he was so goddamn fucking sorry. Some of it was lies, and some of it was true, especially the part about being so god-damn fucking sorry, but none of it surprised Vince, not even when Clarke began to cry.

What surprised him—what surprised all of them—was Clarke’s girlfriend hiding in the bathroom, dressed in daisy print panties and a sweatshirt that said Corman High Varsity. All of seventeen and soaring on meth and clutching a little.22 in one hand. She was listening in when Roy Klowes asked Clarke if she was around, said that if Clarke’s bitch blew all of them, they could cross two hundred bucks off the debt right there. Roy Klowes had walked in the bathroom, taking his cock out of his pants to have a leak, but the girl had thought he was unzipping for other reasons and opened fire. Her first shot went wide and her second shot went into the ceiling, because by then Roy was whacking her with his machete, and it was all sliding down the red hole, away from reality and into the territory of bad dream.

“I’m sure he lost some of the money,” Race said. “Could be he lost as much as half what we set him up. But if you think Dean Clarke put the entire sixty grand into that one trailer, I can’t help you.”

“Maybe he did have some of it tucked away. I’m not saying you’re wrong. But I don’t see why it would wind up with the sister. Could just as easily be in a Mason jar, buried somewhere in his backyard. I’m not going to pick on some pathetic hooker for fun. If we find out she’s suddenly come into money, that’s a different story.”

“I was six months setting this deal up. And I’m not the only one with a lot riding on it.”

“Okay. Let’s talk about how to make it right in Vegas.”

“Talk isn’t going to make anything right. Riding is. His sister is in Show Low today, but when she finds out her brother and his little honey got painted all over their ranch—”

“You want to keep your voice down,” Vince said.

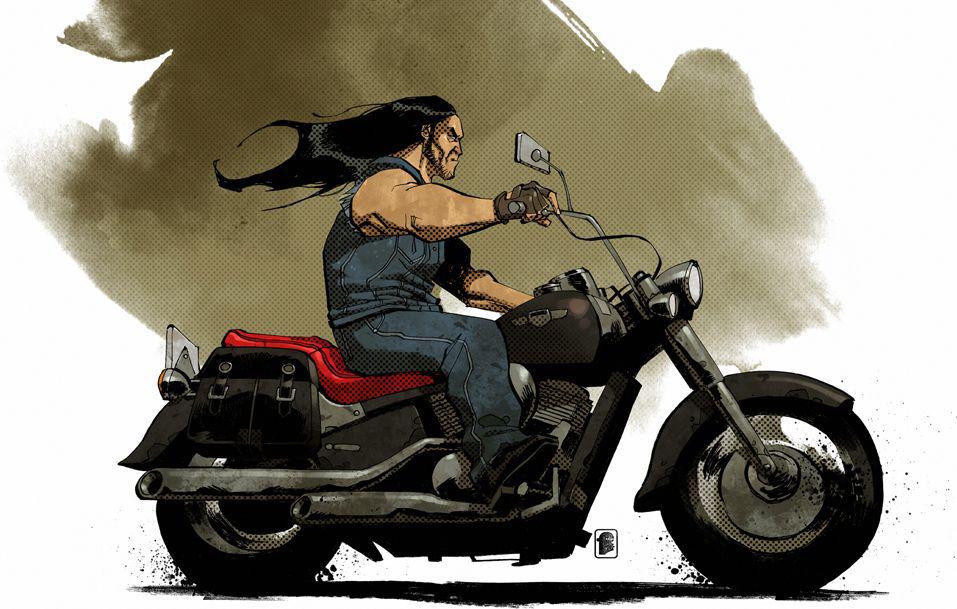

Lemmy watched them with his arms folded across his chest, a few feet to Vince’s left, but ready to move if he had to get between them. The others stood in groups of two and three, bristly and road dirty, wearing leather jackets or denim vests with the gang’s patch on them: a skull in an Indian headdress, above the legend The Tribe • Live on the Road, Die on the Road. They had always been The Tribe, although none of them were Indian, except for Peaches, who claimed to be half-Cherokee, except when he felt like saying he was half-Spaniard or half-Inca. Doc said he could be half-Eskimo and half-Viking if he wanted, it still added up to all retard.

“The money is gone,” Vince said to his son. “The six months too. See it. ”

His son stood there, the muscles bunched in his jaw, not speaking. His knuckles white on the flask in his right hand. Looking at him now, Vince was struck with a sudden image of Race at the age of six, face just as dusty as it was now, tooling around the gravel driveway on his green Big Wheels, making revving noises down in his throat. Vince and Mary had laughed and laughed, mostly at the screwed-up look of intensity on their son’s face, the kindergarten road warrior. He couldn’t find the humor in it now, not two hours after Race had split a man’s head open with a shovel. Race had always been fast, and had been the first to catch up to Clarke when he tried to run in the confusion after the girl started shooting. Maybe he had not meant to kill him. Race had only hit him the once.

Vince opened his mouth to say something more, but there was nothing more. He turned away, started toward the diner. He had not gone three steps, though, when he heard a bottle explode behind him. He turned and saw Race had thrown the flask into the side of the oil rig, had thrown it exactly in the place Vince had been standing only five seconds before. Throwing it at Vince’s shadow maybe.

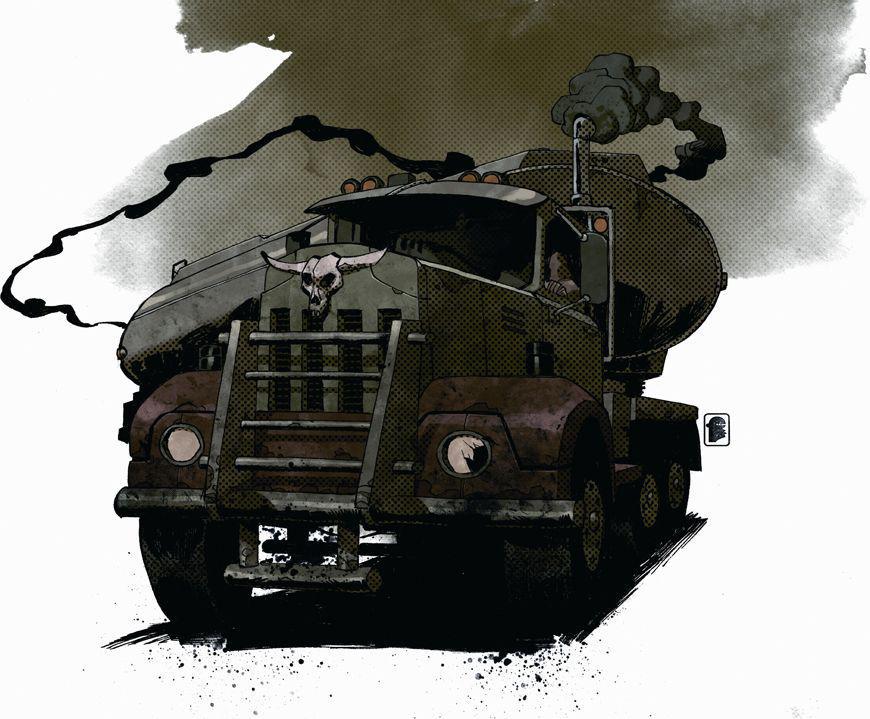

Whisky and chunks of glass dribbled down the battered oil tank. Vince glanced up at the side of the tanker and twitched involuntarily at what he saw there. There was a word stenciled on the side and for an instant Vince thought it said SLAUGHTERIN. But no. It was LAUGHLIN. What Vince knew about Freud could be summed up in less than twenty words—dainty little white beard, cigar, thought kids wanted to fuck their parents—but you didn’t need to know much psychology to recognize a guilty subconscious at work. Vince would’ve laughed if not for what he saw next.

The trucker was sitting in the cab. His hand hung out the driver’s-side window, a cigarette smoldering between two fingers. Midway up his forearm was a faded tattoo, DEATH BEFORE DISHONOR, which made him a vet, something Vince noted, in a distracted sort of way, and immediately filed away, perhaps for later consideration, perhaps not. He tried to think what the guy might’ve heard, measure the danger, figure out if there was a pressing need to haul Laughlin out of his truck and straighten him out about a thing or two.

Vince was still considering it when the semi rumbled to noisy, stinking life. Laughlin pitched his ciggie into the parking lot and released his air brakes. The stacks belched black diesel smoke and the truck began to roll, tires crushing gravel. As the tanker moved away, Vince let out a slow breath and felt the tension begin to drain away. He doubted if the guy had heard anything, and what did it matter if he had? No one with any sense would want to get involved in their shitpull. Laughlin must’ve realized he had been caught listening in and decided to get while the getting was good.

By the time the eighteen-wheeler eased out onto the two-lane highway, Vince had already turned away, brushing through his crew and making for the diner. It was almost an hour before he saw the truck again.

Vince went to piss—his bladder had been killing him for going on thirty miles—and on his return he passed by the others, sitting in two booths. They were quiet, almost no sound from them at all, aside from the scrape of forks on plates and the clink of glasses being set down. Only Peaches was talking, and that was to himself. Peaches spoke in a whisper, and occasionally seemed to flinch, as if surrounded by a cloud of imaginary midges... a dismal, unsettling habit of his. The rest of them occupied their own interior spaces, not seeing each other, staring inwardly at who-knew-what instead. Some of them were probably seeing the bathroom after Roy Klowes finished chopping up the girl. Others might be remembering Clarke facedown in the dirt beyond the back door, his ass in the air and his pants full of shit and the steel-bladed shovel planted in his skull, the handle sticking in the air. And then there were probably a few wondering if they would be home in time for American Gladiators, and whether the lottery tickets they had bought yesterday were winners.

It had been different on the way down to see Clarke. Better. The Tribe had stopped just after sunup at a diner much like this, and while the mood had not been festive, there had been plenty of bullshit, and a certain amount of predictable yuks to go with the coffee and the doughnuts. Doc had sat in one booth doing the crossword puzzle, others seated around him, looking over his shoulder and ribbing each other about what an honor it was to sit with a man of such education. Doc had done time, like most of the rest of them, and had a gold tooth in his mouth in place of the one that had been whacked out by a cop’s nightstick a few years before. But he wore bifocals, and had lean, almost patrician features, and read the paper, and knew things, like the capital of Kenya and the players in the War of the Roses. Roy Klowes took a sidelong look at Doc’s puzzle and said, “What I need is a crossword with questions about fixing bikes or cruising pussy. Like what’s a four-letter word for what I do to your momma, Doc? I could answer that one.”

Doc frowned. “I’d say ‘repulse,’ but that’s seven letters. So I guess my answer would have to be ‘gall.’”

“Gall?” Roy asked, scratching his head.

“That’s right. You gall her. Means you show up and she wants to spit.”

“Yeah and that’s what pisses me off about her. ’Cause I been trying to train her to swaller while I gall her.”

And the men just about fell off their stools laughing. They had been laughing just as hard the next booth over, where Peaches was trying to tell them about why he got his nuts clipped: “What sold me on it was when I saw that I’d only ever have to pay for one vasectomy... which is not something you can say about abortion. There’s theoretically no limit there. None. Every jizzwad is a potential budget buster. You don’t recognize that until you’ve had to pay for a couple of scrapes and begin to think there might be a better use for your money. Also, relationships aren’t ever the same after you’ve had to flush Junior down the toilet. They just aren’t. Voice of experience right here.” Peaches didn’t need jokes, he was funny enough just saying what was on his mind.

Now Vince moved past the cored-out, red-eyed bunch, and took a stool at the counter beside Lemmy.

“What do you think we ought to do about this shit when we get to Vegas?” Vince asked.

“Run away,” Lemmy said. “Tell no one we’re going. Never look back.”

Vince laughed. Lemmy didn’t. He lifted his coffee halfway to his lips but didn’t drink, only looked at it for a few seconds and then put it down.

“Somethin’ wrong with that?” Vince asked.

“It ain’t the coffee that’s wrong.”

“You aren’t going to tell me you’re serious about taking off, are you?”

“We wouldn’t be the only ones, buddy,” Lemmy said. “What Roy did to that girl in the bathroom?”

“She almost shot him,” Vince said, voice low so no one else could hear.

“She wasn’t but seventeen.”

Vince did not reply and anyway no reply was expected.

“Most of these guys have never seen anything that heavy and I think a bunch—the smart ones—are going to scatter to the four corners of the earth as soon as they can. Find a new purpose for being.” Vince laughed again, but Lemmy only glanced at him sidelong. “Listen now, Cap. I killed my brother driving blind drunk when I was eighteen. And when I woke up I could smell his blood all over me. I tried to kill myself in the Corps to make up for it, but the boys in the black pajamas wouldn’t help me. And what I remember mostly about the war is the way my own feet smelled when they got jungle rot. Like carrying a toilet around in my boots. I been in jail, like you, and what was worst wasn’t the things I did or saw done. What was worst was the smell on everyone. Armpits and assholes. And that was all bad. But none of it has anything on the Charlie Manson shit we’re driving away from. Thing I can’t get away from is how it stank in the place. After it was over. Like being stuck in a closet where someone took a shit. Not enough air, and what there was wasn’t any good.” He paused, turned on his stool to look sidelong at Vince. “You know what I been thinking about ever since we drove away? Lon Refus moved out to Denver and opened a garage. He sent me a postcard of the Flatirons. I been wondering if he could use an old guy to twist a wrench for him. I been thinking I could get used to the smell of pines.”

He was quiet again, then shifted his gaze to look at the other men in their booths. “The half that doesn’t take a walk will be looking to get back what they lost, one way or another, and you don’t want any part of how they’re going to do it. ’Cause there’s going to be more of this crazy meth shit. This is just beginning. The tollbooth where you get on the turnpike. There’s too much money in it to quit, and everyone who sells it does it too, and the ones who do it make big fucking messes. The girl who tried to shoot Roy was on it, which is why she tried to kill him, and Roy is on it himself, which is why he had to whack her forty fucking times with his asshole machete. Who the fuck besides a meth-head carries a machete, anyhow?”

“Don’t get me started on Roy. I’d like to stick Little Boy up his ass and watch the light shoot out his eyes,” Vince told him, and it was Lemmy’s turn to laugh then. Coming up with deranged uses for Little Boy was one of the running jokes between them. Vince said, “Go on. Say your say. You been thinkin’ about it the last hour.”

“How would you know that?”

“You think I don’t know what it means when I see you sittin’ straight up on your sled?”

Lemmy grunted and said, “Sooner or later the cops are going to land on Roy or one of these other crankies and they’ll take everyone around them down with them. Because Roy and the guys like him aren’t smart enough to get rid of the shit they stole from crime scenes. None of them are smart enough not to brag to their girlfriends about what they been up to. Hell. Half of them are carrying rock right now. All I’m saying.”

Vince scrubbed a hand along the side of his beard. “You keep talking about the two halves, the half that’s going to take off and the half that isn’t. You want to tell me which half Race is in?”

Lemmy turned his head and grinned unhappily, showing the chip in his tooth again. “You need to ask?”

The truck with LAUGHLIN on the side was laboring uphill when they caught up to it around three in the afternoon.

The highway wound its lazy way up a long grade, through a series of switchbacks. With all the curves there was no obvious place to pass. Race was out front again. After they departed from the diner, he had sped off, increasing his lead on the rest of The Tribe by so much that sometimes Vince lost sight of him altogether. But when they reached the truck, his son was riding the guy’s bumper.

The ten of them rode up the hill in the rig’s boiling wake. Vince’s eyes began to tear and run.

“ Fucking truck,” Vince screamed, and Lemmy nodded. Vince’s lungs were tight and his chest hurt from breathing its exhaust and it was hard to see. “ Get your miserable fat-ass truck out of the way! ” Vince hollered.

It was a surprise, catching up to the truck here. They weren’t that far from the diner... twenty miles, no more. LAUGHLIN must’ve pulled over somewhere else for a while—but there was nowhere else. Possibly he had parked his rig in the shade of a billboard for a siesta. Or threw a tire and needed to stop and put on a new one. Did it matter? It didn’t. Vince wasn’t even sure why it was on his mind, but it nagged.

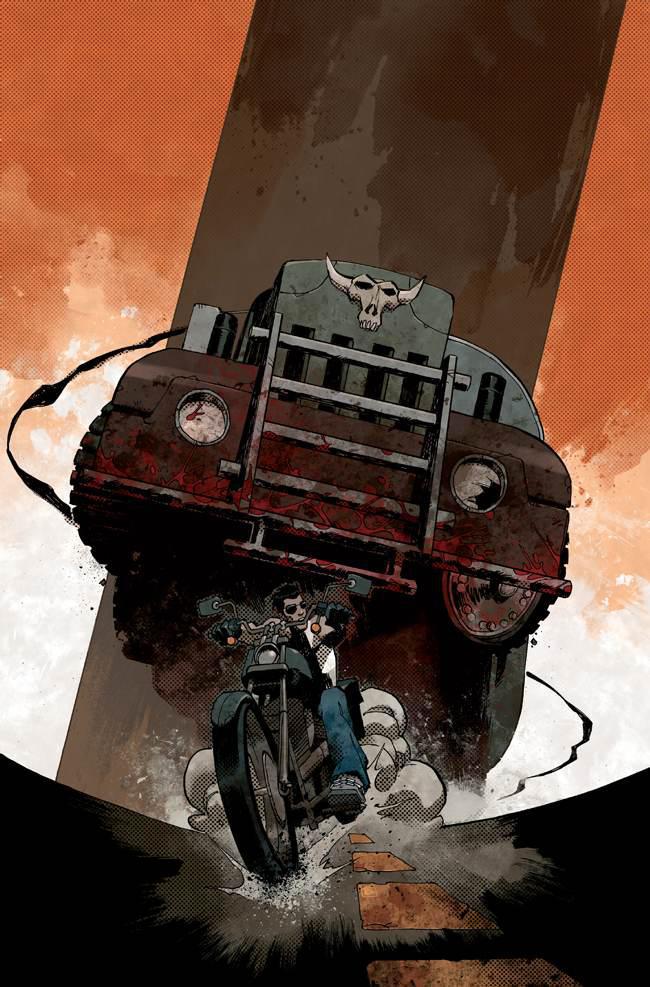

Just past the next bend in the road, Race leaned his Softail Deuce into the lane for oncoming traffic, lowered his head, and accelerated from thirty to seventy. The bike squatted, then leaped. He cut in front of the truck as soon as he was ahead of it—slipping back into the right-hand lane just as a pale yellow Lexus blew past, going the other way. The driver of the Lexus pounded her horn, but the meep-meep sound of it was almost immediately lost in the overpowering wail of the truck’s air horn.

Vince had spotted the Lexus coming and for a moment had been sure he was about to see his son go head-on into it, Race one second, roadmeat the next. It took a few moments for his heart to come back down out of his throat.

“ Fucking psycho,” Vince yelled at Lemmy.

“ You mean the guy in the truck? ” Lemmy hollered back, as the blast of the air horn finally died away. “ Or Race? ”

“ Both! ”

By the time the truck swung through the next curve, though, Laughlin seemed to have come to his senses, or had finally looked in the mirror and noticed the rest of The Tribe roaring along behind him. He put his hand out the window—that sundarkened and veiny hand, big-knuckled and blunt-fingered—and waved them by.

Immediately, Roy and two others swung out and thundered past. The rest went in twos. It was nothing to pass once the go-to was clear, the truck laboring along at barely thirty. Vince and Lemmy swept out last, passing just before the next switchback. Vince cast a look up toward the driver on their way by but could see nothing except that dark hand hanging out against the door. Five minutes later they had left the truck so far behind them they couldn’t hear it anymore.

There followed a stretch of high, open desert, sage and saguaro, cliffs off to the right, striped in chalky shades of yellow and red. They were riding into the sun now, pursued by their own lengthening shadows. Houses and a few trailers whipped by as they blew through a sorry excuse for a township. The bikes were strung out across almost half a mile, with Vince and Lemmy riding close to the back. But not far beyond the town, Vince saw the rest of The Tribe bunched up at the side of the road, just before a four-way intersection—the crossing for Route 6.

Beyond the intersection, to the west, the highway they had been following was torn down to dirt. A diamond-shaped orange sign read CONSTRUCTION NEXT 20 MILES BE PREPARED TO STOP. In the distance, Vince could see dump trucks and a grader. Men worked in clouds of red smoke, the clay stirred up and drifting across the tableland.

He hadn’t known there would be roadwork here, because they hadn’t come this way. It had been Race’s suggestion to return by the back roads, which had suited Vince fine. Driving away from a double homicide, it seemed like a good idea to keep a low profile. Of course that wasn’t why Race had suggested it.

“What?” Vince said, slowing and putting his foot down. As if he didn’t already know.

Race pointed away from the construction, down Route 6. “We go south on 6, we can pick up I-40.”

“In Show Low,” Vince said. “Why does this not surprise me?”

It was Roy Klowes spoke next. He jerked a thumb toward the dump trucks. “Bitch of a lot better than doing five an hour through that shit for twenty miles. No thank you. I’d rather ride easy and maybe pick up sixty grand along the way. That’s my think on it.”

“Did it hurt?” Lemmy asked Roy. “Having a thought? I hear it hurts the first time. Like when a chick gets her cherry popped.”

“Fuck you, Lemmy,” Roy said.

“When I want your think,” Vince said, “I’ll be sure to ask for it, Roy. But I wouldn’t hold your breath.”

Race spoke, his voice calm, reasonable. “We get to Show Low, you don’t have to stick around. Neither of you. No one’s going to hold it against you if you just want to ride on.”

So there it was.

Vince looked from face to face. The young men met his gaze. The older ones, the ones who had been riding with him for decades, did not.

“I’m glad to hear no one will hold it against me,” Vince said. “I was worried.”

A memory struck him then: riding with his son in a car at night, in the GTO, back in the days he was trying to go straight, be a family man for Mary. The details of the journey were lost now; he couldn’t recall where they were coming from or where they had been going. What he remembered was looking into the rearview mirror at his ten-year-old’s dusty, sullen face. They had stopped at a hamburger stand, but the kid didn’t want dinner, said he wasn’t hungry. The kid would only settle for a Popsicle, then bitched when Vince came back with lime instead of grape. He wouldn’t eat it, let the Popsicle melt on the leather. Finally, when they were twenty miles away from the hamburger stand, Race announced that his belly was growling.

Vince had looked into the rearview mirror and said, “You know, just because I’m your father doesn’t mean I got to like you.” And the boy had stared back, his chin dimpling, struggling not to cry, but unwilling to look away. Returning Vince’s look with bright, hating eyes. Why had Vince said that? The notion crossed his mind that if he had known some other way to talk to Race, there would’ve been no Fallujah and no dishonorable discharge for ditching his squad, taking off in a Humvee while mortars fell; there would’ve been no Dean Clarke and no meth lab and the boy would not feel the need to be out front all the time, blasting along at seventy on his hot-shit jackpuppy when the rest of them were doing sixty. It was him the kid was trying to leave behind. He had been trying all his life.

Vince squinted back the way they had come... and there was that goddamn truck again. Vince could see it through the trembling waves of heat on the road, so it seemed half-mirage, with its towering stacks and silver grille: LAUGHLIN. Or SLAUGHTERIN, if you were feeling Freudian. Vince frowned, distracted for a moment, wondering again how they had been able to catch up and pass a guy who’d had almost an hour lead on them.

When Doc spoke, his voice was almost shy with apology. “Might be the thing to do, boss. Sure would beat twenty miles of dirt bath.”

“Well. I wouldn’t want any of you to get dirty,” Vince said.

And he pushed away from the side of the road, throttled up, and turned left onto 6, leading them away toward Show Low.

Behind him, in the distance, he could hear the truck changing gears, the roar of the engine climbing in volume and force, whining faintly as it thundered across the plain.

The country was red and yellow stone, and they saw no one on the narrow, two-lane road. There was no breakdown lane. They crested a rise, then began to descend into a canyon’s slot, following the road as it wound steadily down. To the left was a battered guardrail, and to the right was an almost sheer face of rock.

For a while Vince rode out front beside Lemmy, but then Lemmy fell back and it was Race partnered beside him, the father and the son riding side by side, the wind rippling Race’s movie-star black hair back from his brow. The sun, now on the western side of the sky, burned in the lenses of the kid’s shades.

Vince watched him from the corners of his eyes for a moment. Race was sinewy and lean, and even the way he sat on his bike seemed an act of aggression, the way he slung it around the curves, tilting to a forty-five-degree angle over the blacktop. Vince envied him his natural athletic grace, and yet at the same time, somehow Race managed to make riding a motorcycle look like work. Whereas Vince himself had taken to it because it was the furthest thing from work. He wondered idly if Race was ever really at ease with himself and what he was doing.

Vince heard the grinding thunder of a big engine behind him and took a long, lazy look back over his shoulder just in time to see the truck come bearing down on them. Like a lion breaking cover at a watering hole where a bunch of gazelles were loafing. The Tribe was rolling in bunches, as always, doing maybe forty-five down the switchbacks, and the truck was rushing along at closer to sixty. Vince had time to think, He’s not slowing down, and then LAUGHLIN slammed through the three running at the back of the pack with an eardrum-stunning crash of steel on steel.

Bikes flew. One Harley was thrown into the rock wall, the rider—John Kidder, sometimes known as Baby John—catapulting off it, tossed into the stone, then rebounding and disappearing under the steel-belted tires of LAUGHLIN’s truck. Another rider (Doc, no, not Doc) was driven into the left lane. Vince had the briefest glance of Doc’s pale and astonished face, mouth opening in an O, the twinkle of the gold tooth he was so proud of. Wobbling out of control, Doc struck the guardrail and went over his handlebars, flung into space. His Harley flipped over after him, the hardcase breaking open and spilling laundry. The truck chewed up the fallen bikes. The big grille seemed to snarl.

Then Vince and Race swung around another hard curve side by side, leaving it all behind.

The blood surged to Vince’s heart, and for a moment there was a dangerous pinching in his chest. He had to fight for his next breath. The instant the carnage was out of sight, it was hard to believe it had really happened. Hard to believe the spinning bikes hadn’t taken out the speeding truck, too. Yet he had just finished coming around the bend when Doc crashed into the road ahead of them. His bike landed on top of his body with an echoing clang. His clothes came floating after. Doc’s sleeveless denim jacket came drifting down last, ballooning open, caught for a moment on an updraft. Over a silhouette of Vietnam in gold thread was the legend: WHEN I GET TO HEAVEN THEY’LL LET ME IN BECAUSE I’VE ALREADY BEEN TO HELL IRON TRIANGLE 1968. The clothes, the owner of the clothes, and the owner’s ride had dropped from the terrace above, falling seventy feet to the highway below.

Vince jerked the handlebars, swerving around the wreck with one boot heel skimming the patched asphalt. His friend of thirty years, Doc Regis, was now a six-letter word for lubricant: grease. He was facedown, but his teeth were glistening in a slick of blood next to his left ear, the goldie among them. His shins had come out through the backs of his legs, poles of shining red bone poking through his jeans. All this Vince saw in an instant, then wished he could un -see. The gag muscles fluttered in his throat and when he swallowed, there was a burning taste of bile.

Race swung around the other side of the ruin that had been Doc and Doc’s bike. He looked sideways at Vince, and while Vince could not see his eyes behind his shades, his face was a rigid, stricken thing... the expression of a small kid up past his bedtime who has walked in on his parents watching a grisly horror movie on DVD.

Vince looked back again and saw the remnants of The Tribe coming around the bend. Just seven now. The truck howled after, swinging around the curve so fast that the long tank it was hauling lurched hard to one side, coming perilously close to tipping, its tires smoking on the blacktop. Then it steadied and bore on, striking Ellis Harbison. Ellis was launched straight up into the air, as if bounced off a diving board. He almost looked funny, pinwheeling his arms against the blue sky—at least until he came down and went under the truck. His ride turned end over end before being swatted entirely aside by the eighteen-wheeler.

Vince caught a jittery glimpse of Dean Carew as the truck caught up to him. The truck butted the rear tire of his bike. Dean high-sided and came down hard, rolling at fifty miles an hour along the highway, the asphalt peeling his skin away, his head bashing the road again and again, leaving a series of red punctuation marks on the chalkboard of the pavement.

An instant later the tanker ate Dean’s bike, bang, thump, crunch, and the lowrider Dean had still been making payments on exploded, a parachute of flame bursting open beneath the truck. Vince felt a wave of pressure and heat against his back, shoving him forward, threatening to lift him off the seat of his bike. He thought the truck itself would go up, slammed right off the road as the oil tanker detonated in a column of fire. But it didn’t. The rig came thundering through the flames, its sides streaked with soot and black smoke belching from its undercarriage, but otherwise undamaged and going faster than ever. Vince knew Macks were fast—the new ones had a 485 power plant under the hood—but this thing...

Supercharged? Could you supercharge a goddamn semi?

Vince was moving too fast, felt his front tire beginning to slurve about. They were close to the bottom of the slope now, where the road leveled out. Race was a little ahead. In his rearview he could see the only other survivors: Lemmy, Peaches, Roy. And the truck was closing in again.

They could beat it on a rise—in a heartbeat—but now there were no rises. Not for the next twenty miles, if his memory was right. It was going to get Peaches next, Peaches who was funniest when he was trying to be serious. Peaches threw a terrified glance back over his shoulder, and Vince knew what he was seeing: a chrome cliff. One that was moving in.

Fucking think of something. Lead them out of this.

It had to be him. Race was still riding okay, but he was on autopilot, face frozen, fixed forward as if he had a sprained neck and was wearing a brace. A thought struck Vince then—terrible but curiously certain—that this was how Race had looked the day in Fallujah that he drove away from the men in his squad, while the mortar rounds dropped around them.

Peaches put on a burst of speed and gained a little on the truck. It blasted its air horn, as if in frustration. Or laughter. Either way, the old Georgia Peach had only gained a stay of execution. Vince could hear the trucker—maybe named Laughlin, maybe a devil from Hell—changing gears. Christ, how many forward did he have? A hundred? He started to close the distance. Vince didn’t think Peaches would be able to squirt ahead again. That old flathead Beezer of his had given all it had to give. Either the truck would take him or the Beez would blow a head gasket and then the truck would take him.

BRONK! BRONK! BRONK-BRONK-BRONK!

Shattering a day that was already shattered beyond repair... but it gave Vince an idea. It depended on where they were. He knew this road. He knew them all, out here, but he had not been this way in years, and could not be sure now, on the fly, if they were where he thought they were.

Roy threw something back over his shoulder, something that twinkled in the sun. It struck LAUGHLIN’s dirty windshield and flew off. The fucking machete. The truck bellowed on, blowing double streams of black smoke, the driver laying on that horn again—

BRONK-BRONK! BRONK! BRONK-BRONK-BRONK!

—in blasts that sounded weirdly like Morse.

If only... Lord, if only...

And yes. Up ahead was a sign so filthy it was only barely possible to read it: CUMBA 2.

Cumba. Goddam Cumba. A played-out little mining town on the side of a hill, a place where there were maybe five slots and one old geezer selling Navajo blankets made in Laos.

Two miles wasn’t much time when you were already doing eighty. This would have to be quick, and there would only be one chance.

The others made fun of Vince’s sled, but only Race’s ridicule had a keen edge to it. The bike was a rebuilt Kawasaki Vulcan 800 with Cobra pipes and a custom seat. Leather as red as a fire alarm. “The old man’s La-Z-Boy,” Dean Carew had once called the seat.

“Fuck that,” Vince had replied indignantly, and when Peaches, solemn as a preacher, had said, “I’m sure you have,” they all broke up.

The Tribe called the Vulcan a rice-burner, of course. Also Vince’s Tojo Mojo El Rojo. Doc—Doc who was now spread all over the road behind them—liked to call it Miss Fujiyama. Vince only smiled as though he knew something they didn’t. Maybe he even did. He’d had the Vulcan up to one-twenty and had stopped there. Pussied out. Race wouldn’t have, but Race was a young man and young men had to know where things ended. One-twenty had been enough for Vince, but he’d known there was more. Now he would find out how much.

He grasped the throttle and twisted it all the way to the stop.

The Vulcan responded not with a snarl but a cry and almost tore out from under him. He had a blurred glimpse of his son’s white face and then he was past, in the lead, riding the rocket, desert smells packing his nose. Up ahead was a dirty string of asphalt angling off to the left, the road to Cumba. Route 6 went past in a long, lazy curve to the right. Toward Show Low.

Vince looked in his right-hand rearview and saw the others had bunched, and that Peaches still had the shiny side up. Vince thought the truck could have taken Peaches—maybe all the others—but he was laying back a little, knowing as well as Vince did that for the next twenty miles there were no upgrades. Beyond the turn-off to Cumba, the highway was elevated, and a guardrail ran along either side of it; Vince thought miserably of cattle in the chute. For the next twenty miles, the road belonged to LAUGHLIN.

Please let this work.

He let off the throttle and began squeezing the hand brake rhythmically. What the four behind him saw (if they were looking) was a long flash... a short flash... another long flash. Then a pause. Then a repeat. Long... short... long. It was the truck’s air horn that had given him the idea. It only sounded like Morse, but what Vince was flashing with his brake light was Morse.

It was the letter R.

Roy and Peaches might pick it up, Lemmy for sure. And Race? Did they still teach Morse? Had the kid learned it in his war, where squad leaders carried GPS units and bombs were guided around the curve of the world by satellite?

The left turn to Cumba was coming up. Vince had just time enough to flash R one more time. Now he was almost back with the others. He shot his hand left in a gesture The Tribe knew well: follow me off the highway. Laughlin saw it—as Vince had expected—and surged forward. At the same time he did, Vince twisted his throttle again. The Vulcan screamed and leaped forward. He banked right, along the main road. The others followed. But not the truck. LAUGHLIN had already started its turn onto the Cumba spur. If the driver had tried to correct for the main road, he would have rolled his rig.

Vince felt a white throb of elation and reflexively closed his left hand into a triumphant fist. We did it! We fucking did it! By the time he gets that fat-ass truck turned around, we’ll be nine miles from h—

The thought broke off like a branch as he looked again into his rearview. There were three bikes behind him, not four: Lemmy, Peaches, and Roy.

Vince swiveled to the left, hearing the old bones crackle in his back, knowing what he would see. He saw it. The truck, dragging a huge rooster tail of red dust, its tanker too dirty to shine. But there was shine fifty or so yards in front of it; the gleam of the chromed pipes and engine belonging to a Softail Deuce. Race either did not understand Morse, didn’t believe what he was seeing, or hadn’t seen at all. Vince remembered the waxy, fixed expression on his son’s face, and thought this last possibility was most likely. Race had stopped paying attention to the rest of them—had stopped seeing them—the moment he understood LAUGHLIN was not just a truck out of control but one bent on tribal slaughter. He had been just aware enough to spot Vince’s hand gesture, but had lost all the rest to a kind of tunnel vision.

What was that? Panic? Or a kind of animal selfishness? Or were they the same, when you came down to it?

Race’s Harley slipped behind a low swell of hill. The truck disappeared after it and then there was only blowing dust. Vince tried to catch his flying thoughts and put them in some coherent order. If his memory was right again—he knew it was asking a lot of it; he hadn’t been this way in a couple of years—then the spur road ran through Cumba before veering back to rejoin Highway 6 about nine miles ahead. If Race could stay in front—

Except.

Except, unless things had changed, the road went to hard-pan dirt beyond Cumba, and was apt to drift across sandy at this time of year. The truck would do okay, but a motorcycle...

The chances of Race surviving the last four miles of that nine-mile run weren’t good. The chances of him dumping the Deuce and being run over were, on the other hand, excellent.

Images of Race tried to crowd his mind. Race on his Big Wheels: the kindergarten road warrior. Race staring at him from the backseat of the GTO, the Popsicle melting, his eyes bright with hate, the lower lip quivering. Race at eighteen, wearing a uniform and a fuck-you smile, both present and accounted for and all squared away.

Last of all came the image of Race dead on the hardpan, a smashed doll with only his leathers holding him together.

Vince swept the pictures away. They were no help. The cops wouldn’t be, either. There were no cops, not in Cumba. If someone saw the semi chasing the bike, he might call the state police, but the closest one was apt to be in Show Low, drinking java and eating pie and flirting with the waitress while Travis Tritt played on the Rock-Ola.

There was only them. But that was nothing new.

He thrust his hand to the right, then made a fist and patted the air with it. The other three swung over to the side behind him, engines clobbering, the air over their straight pipes shimmering.

Lemmy pulled up beside him, his face haggard and cheesy-yellow. “ He didn’t see the taillight signal! ” he shouted.

“ Didn’t see or didn’t understand! ” Vince yelled back. He was trembling. Maybe it was just the bike throbbing under him. “ Comes to the same! Time for Little Boy! ”

For a moment Lemmy didn’t understand. Then he twisted around and yanked the straps on his right-hand saddlebag. No fancy plastic hardcase for Lemmy. Lemmy was old school all the way.

While he was rooting, there was a sudden, gunning roar. That was Roy. Roy had had enough. He wheeled around and shot back east, his shadow now running before him, a scrawny black gantry-man. On the back of his leather vest was a hideous joke: NO RETREAT NO SURRENDER.

“ Come back, Klowes, you dickwad! ” Peaches bellowed. His hand slipped from his clutch. The Beezer, still in gear, lurched forward almost over Vince’s foot, passed high-octane gas, and stalled. Peaches was almost hurled off but didn’t seem to notice. He was still looking back. He shook his fist; his scant gray hair whirled around his long, narrow skull. “ Come back, you chicken-shit DICKWAAAAD! ”

Roy didn’t come back. Roy didn’t even look back.

Peaches turned to Vince. Tears streamed down cheeks sunflayed by a million rides and ten million beers. In that moment he looked older than the desert he stood on.

“ You’re stronger’n me, Vince, but I got me a bigger asshole. You rip his head off; I’ll be in charge of shittin’ down his neck. ”

“ Hurry up! ” Vince shouted at Lemmy. “ Hurry up, goddamn you! ”

Just when he thought Lemmy was going to come up empty, his old running buddy straightened with Little Boy in his gloved hand.

The Tribe did not ride with guns. Outlaw motorheads like them never did. They all had records, and any cop in Nevada would be delighted to put one of them away for thirty years on a gun charge. One, or all of them. They carried knives, but knives were no good in this situation; witness what had happened to Roy’s machete, which had turned out as useless as the man himself. Except when it came to killing stoned little girls in high school sweaters, that was.

Little Boy, however, while not strictly legal, was not a gun. And the one cop who’d looked at it (“while searching for drugs”—the pigs were always doing that, it was what they lived for) had given Lemmy a skate when Lemmy explained it was more reliable than a road flare if you broke down at night. Maybe the cop knew what he was looking at, maybe not, but he knew that Lemmy was a veteran. Not just from Lemmy’s veteran’s license plate, which could have been stolen, but because the cop had been a vet himself. “Au Shau Valley, where the shit smells sweeter,” he’d said, and they had both laughed and even ended up bumping fists.

Little Boy was an M84 stun grenade, more popularly known as a flash-bang. Lemmy had been carrying it in his saddlebag for maybe five years, always saying it would come in handy someday when the other guys—Vince included—ribbed him about it.

Someday had turned out to be today.

“ Will this old sonofabitch still work? ” Vince shouted as he hung Little Boy over his handlebars by the strap. It didn’t look like a grenade. It looked like a combination thermos bottle and aerosol can. The only grenade-y thing about it was the pull ring duct-taped to the side.

“ I don’t know! I don’t even know how you can— ”

Vince had no time to discuss logistics. He only had a vague idea of what the logistics might be, anyway. “ I have to ride! That fuck’s gonna come out on the other end of the Cumba road! I mean to be there when he does! ”

“And if Race ain’t in front of him?” Lemmy asked. They had been shouting until now, all jacked up on adrenaline. It was almost a surprise to hear a nearly normal tone of voice.

“One way or the other,” Vince said. “You don’t have to come. Either of you. I’ll understand if you want to turn back. He’s my boy.”

“Maybe so,” Peaches said, “but it’s our Tribe. Was, anyway.” He jumped down on the Beezer’s kick, and the hot engine rumbled to life. “I’ll ride witcha, Cap.”

Lemmy just nodded and pointed at the road.

Vince took off.

It wasn’t as far as he’d thought: seven miles instead of nine. They met no cars or trucks. The road was deserted, traffic maybe avoiding it because of the construction back the way they had come. Vince snapped constant glances to his left. For a while he saw red dust rising, the truck dragging half the desert along in its slipstream. Then he lost sight even of its dust, the Cumba spur dropping well out of sight behind hills with eroded, chalky sides.

Little Boy swung back and forth on its strap. Army surplus. Will this old sonofabitch still work? he’d asked Lemmy, and now realized he could have asked the same question of himself. How long since he had been tested this way, running dead out, throttle to the max? How long since the whole world came down to only two choices, live pretty or die laughing? And how had his own son, who looked so cool in his new leathers and his mirrored sunglasses, missed such an elementary equation?

Live pretty or die laughing, but don’t you run. Don’t you fucking run.

Maybe Little Boy would work, maybe it wouldn’t, but Vince knew he was going to take his shot, and it made him giddy. If the guy was buttoned up in his cab, it was a lost cause in any case. But he hadn’t been buttoned up back at the diner. Back there, his hand had been lolling out against the side of the truck. And later, hadn’t he waved them ahead from that same open window? Sure. Sure he had.

Seven miles. Five minutes, give or take. Long enough for a lot of memories of his son, whose father had taught him to change the oil but never to bait a hook; to gap plugs but never how you told a coin from the Denver mint from one that had been struck in San Francisco. Time to think how Race had pushed for this stupid meth deal, and how Vince had gone along even though he knew it was stupid, because it seemed he had something to make up for. Only the time for make-up calls was past. As Vince tore along at eighty-five, bending as low as he could get to cut the wind resistance, a terrible thought crossed his mind, one he inwardly recoiled from but could not blot out—that maybe it would be better for all concerned if LAUGHLIN did succeed in running his son down. It wasn’t the image of Race lifting a shovel into the air and then bringing it down on a helpless man’s head, in a spoiled rage over lost money, although that was bad enough. It was something more. It was the fixed, empty look on the kid’s face right before he steered his bike the wrong way, onto the Cumba road. For himself, Vince had not been able to stop looking back at The Tribe, the whole way down the canyon, as some were run down and the others struggled to stay ahead of the big machine. Whereas Race had seemed incapable of turning that stiff neck of his. There was nothing behind him that he needed to see. Maybe never had been.

There came a loud ka-pow at Vince’s back, and a yell he heard even over the wind and the steady blat of the Vulcan’s engine: “ Mutha-FUCK! ” He looked in the rearview mirror and saw Peaches falling back. Smoke was boiling from between his pipe-stem legs and oil slicked the road behind him in a fan shape that widened as his ride slowed. The Beez had finally blown its head gasket. A wonder it hadn’t happened sooner.

Peaches waved them on... not that Vince would have stopped. Because in a way, the question of whether Race was redeemable was moot. Vince himself was not redeemable; none of them were. He remembered an Arizona cop who’d once pulled them over and said, “Well, look what the road puked up.” And that was what they were: road puke. But those bodies back there had, until this afternoon, been his running buddies, the only thing he had of any value in the world. They had been Vince’s brothers in a way, and Race was his son, and you couldn’t drive a man’s family to earth and expect to live. You couldn’t leave them butchered and expect to ride away. If LAUGHLIN didn’t know that, he would.

Soon.

Lemmy couldn’t keep up with the Tojo Mojo El Rojo. He fell farther and farther behind. That was all right. Vince was just glad Lemmy still had his six.

Up ahead, a sign: WATCH FOR LEFT-ENTERING TRAFFIC. The road coming out of Cumba. It was hardpan dirt, as he had feared. Vince slowed, then stopped, turned off the Vulcan’s engine.

Lemmy pulled up beside. There was no guardrail here. Here in this one place, where 6 rejoined the Cumba road, the highway was level with the desert, although not far ahead it began to climb away from the floodplain once more, turning into the cattle chute again.

“Now we wait,” Lemmy said, switching his engine off as well.

Vince nodded. He wished he still smoked. He told himself that either Race was still shiny-side-up and in front of the truck or he wasn’t. It was beyond his control. It was true, but it didn’t help.

“Maybe he’ll find a place to turn off in Cumba,” Lemmy said. “An alley or somethin’ where the truck can’t go.”

“I don’t think so. Cumba is nothing. A gas station and I think a couple houses, all stuck right on the side of a fucking hill. That’s bad road. At least for Race. No easy way off it.” He didn’t even try to tell Lemmy about Race’s blank, locked-down expression, a look that said he wasn’t seeing anything except the road right in front of his bike. Cumba would be a blur and a flash that he only registered after it was well behind him.

“Maybe—” Lemmy began, but Vince held up his hand, silencing him. They cocked their heads to the left.

They heard the truck first, and Vince felt his heart sink. Then, buried in its roar, the bellow of another motor. There was no mistaking the distinctive blast of a Harley running full out.

“He made it!” Lemmy yelled, and raised his hand for a high-five. Vince wouldn’t give it. Bad luck. And besides, the kid still had to make the turn back onto 6. If he was going to dump, it would be there.

A minute ticked by. The sound of the engines grew louder. A second minute, and now they could see dust rising over the nearest hills. Then, in a notch between the two closest hills, they saw a flash of sun on chrome. There was just time to glimpse Race, bent almost flat over his handlebars, long hair streaming out behind, and then he was gone again. A second after he disappeared—surely no more—the truck flashed through the notch, stacks shooting smoke. LAUGHLIN on the side was no longer visible; it had been buried beneath a layer of dust.

Vince hit the Vulcan’s starter and the engine bammed to life. He gunned the throttle and the frame vibrated.

“Luck, Cap,” Lemmy said.

Vince opened his mouth to reply, but in that moment emotion, intense and unexpected, choked off his wind. So instead of speaking, he gave Lemmy a brief, grateful nod before taking off. Lemmy followed. As always, Lemmy had his six.

Vince’s mind turned into a computer, trying to figure speed versus distance. It had to be timed just right. He rolled toward the intersection at fifty, dropped it to forty, then twisted the throttle again as Race appeared, the bike swerving around a tumbleweed, actually going airborne on a couple of bumps. The truck was no more than thirty feet behind. When Race neared the Y where the Cumba bypass once more joined the main road, he slowed. He had to slow. The instant he did, LAUGHLIN vaulted forward, eating up the distance between them.

“ Jam that motherfuck! ” Vince screamed, knowing Race couldn’t hear over the bellow of the truck. He screamed it again anyway: “ JAM that motherfuck! Don’t slow down! ”

The trucker planned to slam the Harley in the rear wheel, spinning it out. Race’s bike hit the crotch of the intersection and surged, Race leaning far to the left, holding the handlebars only with the tips of his fingers. He looked like a trick rider on a trained mustang. The truck missed the rear fender, its blunt nose lunging into thin air that had held a Harley’s back wheel only a tenth of a second before... but at first Vince thought Race was going to lose it anyway, just spin out.

He didn’t. His high-speed arc took him all the way to the far side of Route 6, close enough to the bike-killing shoulder to spume up dust, and then he was scat-gone, gunning down Route 6 toward Show Low.

The truck went out into the desert to make its own turn, rumbling and bouncing, the driver down-shifting through the gears fast enough to make the whole rig shudder, the tires churning up a fog of dust that turned the blue sky white. It left a trail of deep tracks and crushed sagebrush before regaining the road and once more setting out after Vince’s son.

Vince twisted the left handgrip and the Vulcan took off. Little Boy swung frantically back and forth on the handlebars. Now came the easy part. It might get him killed, but it would be easy compared to the endless minutes he and Lemmy had waited before hearing Race’s motor mixed in with LAUGHLIN’s.

His window won’t be open, you know. Not after he just got done running through all that dust.

That was also out of his control. If the trucker was buttoned up, he’d deal with that when the moment came.

It wouldn’t be long.

The truck was doing around sixty. It could go a lot faster, but Vince didn’t mean to let him get all the way through those who-knew-how-many gears of his until the Mack hit warp-speed. He was going to end this now for one of them. Probably for himself, an idea he did not shy from. He would at the least buy Race more time; given a lead, Race could beat the truck to Show Low easily. More than just protecting Race, though, there had to be balance to the scales. Vince had never lost so much so fast, six of The Tribe dead on a stretch of road less than half a mile long. You didn’t do that to a man’s family, he thought again, and drive away.

Which was, Vince saw at last, maybe LAUGHLIN’s own point, his own primary operating principle... the reason he had taken them on, in spite of the ten-to-one odds. He had come at them, not knowing or caring if they were armed, picking them off two and three at a time, even though any one of the bikes he had run down could’ve sent the truck out of control and rolling, first a Mack, and then an oil-stoked fireball. It was madness, but not incomprehensible madness. As Vince swung into the left-hand lane and began to close the final distance, the truck’s ass end just ahead on his right, he saw something that seemed not only to sum up this terrible day but to explain it, in simple, perfectly lucid terms. It was a bumper sticker. It was even filthier than the Cumba sign, but still readable.

PROUD PARENT OF A CORMAN HIGH HONOR ROLL STUDENT!

Vince pulled even with the dust-streaked tanker. In the cab’s long driver’s-side rearview, he saw something shift. The driver had seen him. In the same second, Vince saw that the window was shut, just as he’d feared.

The truck began to slide left, crossing the white line with its outside wheels.

For a moment Vince had a choice: back off or keep going. Then the computer in his head told him the choice was already past; even if he hit the brakes hard enough to risk dumping his ride, the final five feet of the filthy tank would swat him into the guardrail on his left like a fly.

Instead of backing off he increased speed even as the left lane shrank, the truck forcing him toward that knee-high ribbon of gleaming steel. He yanked the flash-bang from the handlebars, breaking the strap. He tore the duct tape away from the pull ring with his teeth, the strap’s shredded end spanking his cheek as he did so. The ring began to clatter against Little Boy’s perforated barrel. The sun was gone. Vince was flying in the truck’s shadow now. The guardrail was less than three feet to his left; the side of the truck three feet to his right and still closing. Vince had reached the plate hitch between the tanker and the cab. Now he could only see the top of Race’s head; the rest of him was blocked by the truck’s dirty maroon hood. Race was not looking back.

He didn’t think about the next thing. There was no plan, no strategy. It was just his road-puke self saying fuck you to the world, as he always had. It was, when you came right down to it, The Tribe’s only raison d’être.

As the truck closed in for the killing side-stroke, and with absolutely nowhere to go, Vince raised his right hand and shot the truck driver the bird.

He was pulling even with the cab now, the truck bulking to his right like a filthy mesa. It was the cab that would take him out.

There was movement from inside: that deeply tanned arm with its Marine Corps tattoo. The muscle in the arm bunched as the window slid down into its slot, and Vince realized the cab, which should have swatted him already, was staying where it was. The trucker meant to do it, of course he did, but not until he had replied in kind. Maybe we even served in different units together, Vince thought. In the Au Shau Valley, say, where the shit smells sweeter.

Дата добавления: 2015-10-26; просмотров: 170 | Нарушение авторских прав

| <== предыдущая страница | | | следующая страница ==> |

| IV Make up a situation of your own; use from five to ten words and word-combinations under study. | | | CLASS PHONETIC EXERCISES FOR PRACTISING SENTENCE PATTERNS |