Читайте также:

|

All six Gardena poker rooms were single-story buildings with the ambiance of airport gate waiting areas. They were clean, with high ceilings and functional furnishings. About two-thirds of the floor was segregated by a rail. Outside the rail was a restaurant, bar, TV room (mostly tuned to games for illegal sports betting), guard desk, cashier, and the allimportant board, where all the games and players waiting for seats were listed. Lots of people were hanging around-some waiting for seats, some doing various kinds of business, and some just passing the time. Inside was poker.

The players I wanted would arrive around nine o'clock in the evening. Tom and I had intended to arrive at four o'clock, but getting barred at the Horseshoe had cost us over an hour. From four o'clock to six o'clock there is a switchover from the afternoon to the evening crowds, so you're sure to get a seat. I wanted a few hours to get used to the table. Robert had cautioned against starting at a low-limit game or playing tight at the beginning. I had the advantage: I at least knew the Gardena game vicariously, while the other players didn't know me at all. When you have the advantage, you exploit it; you don't fritter it away to get your bearings or build up your confidence. It's easy to become timid when you don't know what you're doing, but in a competitive situation you have to think about your knowledge relative to what the other players know. My plan was for the good players to arrive to find me well ahead in the game, playing with relaxed confidence. I was probably cocky enough in those days to imagine them reacting with fear, or at least respect. It did not go according to plan.

We were playing Five-Card Draw, jackpots high with a bug (a wild card that can only be used to complete a straight or flush, or as an ace). There was an ante and no blinds. I have been told that lowball was more popular, but I saw more high myself. They say June is a slow month, however, and things may not have been typical. There were five players at the table, none of whom paid the slightest attention when I sat down. They ranged in age from about 25 to 50. As a group, they looked like midlevel office workers after a two-day bus ride, not colorful Damon Runyon characters or dangerous sharpies fresh out of jail. My game collected $10 every half hour from each player, metered by a large clock on the wall with red lights at each half hour point. When the light went on, the chip girls made the rounds for the house money.

The game was fast, but not as fast as Robert had coached me. When you pay by the hour, time is money. I was prepared for a hand a minute. That's fast but not impossible for modern hold 'em with a nonplaying, professional dealer. But Five Card-Draw with six players requires 35 to 40 cards dealt on a typical hand, while six hold 'em players need only 17. Amateur dealers who are playing hands slow things down as well. It's true, there are only half as many betting rounds in draw poker as hold 'em, but 60 seconds is still a very short time to physically manage the chips and cards, much less think about the betting. Anyway, I think we played at only half that rate, about what I was used to at serious private games. No one wasted time, but I had no trouble playing unrushed poker without anyone expressing annoyance. I got two flush draws in the first hour-one, I filled and won a small pot without showing; the other, I didn't fill and bluffed to win another small pot. I got a few pairs worth playing, but none improved on the draw. I was behind a little, but not seriously, and I was playing comfortably. I was getting action-people would open and see some of my raises-but also respect-people would sometimes fold to my raises as well. So far, so good.

One big difference between Gardena card rooms and casinos is the amount of cheating. Casinos invest in the best available security to prevent players from cheating the house, and the same equipment and policies keep players from cheating each other. Professional dealers also act as a safeguard; in Gardena, players dealt the hands. A floorman was available, but only when called. He did not watch every hand at every table. The most important difference is the relationship of the house to the players. Card rooms cater to the regulars, the people who come in every day and pay rent. If a tourist or dabbler walks out mad, that's no great loss.

Casinos, however, tend to regard any dollar that comes in the door as rightfully belonging to the house. They take a limited amount, because if everyone always lost, no one would come back. Every dollar professional poker players win in a casino from tourists and dabblers counts against that limit. Casinos tolerate professionals because their reputations attract business and they fill out tables. They do not tolerate cheaters because they not only take money the house could have won, they drive away business and hurt reputation. Card rooms like regulars; casinos like losers.

Cheating

Robert told me to watch for chip stealing (say what you will about Las Vegas being tacky, you don't have to worry about your chips when you go to the bathroom), signaling, and passing cards. A new player could not expect to get help from the floorman, especially if the other players at the table claimed to have seen nothing. This kind of thing was more common at the lower limits, but at all tables the regulars tended to close ranks against newcomers. The card room could not exist as an economic institution if strangers could walk in and help themselves to money.

Subtle collusion worried me more. There are two things a group of regulars can do to conspire against a newcomer. Neither requires any overt cheating or prior agreement, and players do them naturally, even unconsciously.

The first tactic is to fold all but the strongest hand among the regulars. That means I win the same pots I would anyway, but I collect from only one player instead of from two or more. That's crippling to long-term expected value. It would be overt cheating for the players to compare hands and select the strongest, but if regulars do not try to play deceptively and don't try to win from each other whenever I'm also in the pot, they can figure out pretty quickly who the designated champion should be. Of course, I can try to pick up on this as well, but they've spent hundreds or thousands of hours scrutinizing each other's play and mannerisms-they will have a big edge at this aspect of the game. Whenever I fold, they can revert to their regular game.

Another form of collusion is two regulars raising each other back and forth when I'm in the pot. Although the amounts of the raises are limited, Gardena has no limit on the number of raises. Therefore, two players against me can play effective table stakes poker whenever they choose, while I can only play limit. This tactic is less worrying. Unless the regulars have a formal profit-splitting arrangement, the raiser with the weak hand loses money. Regulars might pass an extra raise or two back and forth as favors, but only overt cheaters would try to get me all-in. Also, the colluders have to bet $2 for every $1 I bet. That's a steep price to pay for the option to evade the limit. Years later, I saw a similar kind of cheating on the Chicago Mercantile Exchange.

I thought I spotted the first kind of collusion in Gardena. When I was in a pot, I usually seemed to be drawing against exactly one other player. Other people won pots before the draw or played in three- and four-way hands. Not me. By watching this carefully, I thought I could get the edge back. If the regulars were not playing deceptively before I folded, I didn't have to worry about being bluffed or about people drawing out straights or flushes. I'd be going up against high pairs, two pairs, and threes-seldom weaker hands. Moreover, I thought I could get a clue to the predraw strength of their hands by the way they played.

In this situation, it doesn't pay to draw to a straight or flush. You don't make enough from one other bettor when you hit to make up for the times you don't hit. Bluffing isn't profitable either, because the designated champion will call much more frequently than a purely profitmaximizing player. On the other hand, a low pair that would normally be folded is a good hand. If you draw two pair or three of a kind, you will usually win against one other bettor who started with a higher pair. If you don't improve, you fold after the draw. However, to disguise the fact that you're throwing away all your straight and flush draws and playing low pairs instead, you have to draw only one card occasionallysay, when you're dealt trips.

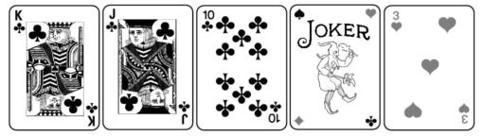

Anyway, that's how I was playing, and it seemed to work pretty well. I was up quite a bit when I was dealt an interesting hand that exists only in this kind of poker. I got king, jack, and ten, all of clubs, and the bug. In most kinds of poker, a player who has an incomplete flush (the famous "four flush") or straight has a reasonably low chance of completing it. For example, if you have four cards of the same suit in draw poker without wild cards, there are 9 more of the suit in the deck out of the 47 cards you haven't seen. The chance of drawing one of them is 9/47, or 19 percent. In hold 'em, if you have an open-ended straight draw after the flop, 8 of the remaining 47 cards will fill it; 340 out of the 1,081 two-card combinations you could get on the turn and river, 31 percent, give you the straight.

But in draw poker with a bug, if you get three suited cards in a row, plus the bug, 22 out of the 48 remaining cards in the deck will give you a straight, flush, or straight flush. That's a 46 percent chance. A lot of the poker rules for playing straight and flush draws are based on the assumption that you have a low chance of completing. My hand wasn't quite this good, but there were 12 cards (any ace, queen, or nine) that would give me a straight and 10 cards (any club) that would give me a flush. That double counts the ace, queen, and nine of clubs, any of which would give me a straight flush. So I had 9/48 = 19 percent chance of a straight, 7/48 = 15 percent chance of a flush, and 3/48 = 6 percent chance of a straight flush. Overall, I had a 40 percent chance of filling.

The Betting

Harrison opened the betting, and Jason raised. I knew the first names of the people at the table and they knew mine, but no one had offered, or asked for, any more information. Harrison had a California cowboy look, with a dirty flannel shirt, string tie, and boots; Jason was a younger, red-faced guy in jeans and a blue oxford cloth shirt, wearing his hippielength hair tied back with a leather braid. Later I learned that Harrison owned racehorses and had a cattle ranch as well, so it wasn't a costume. He treated me very nicely on a subsequent visit to the racetrack. Jason was a student but getting a bit old for not having picked a field of study or enrolled in a degree program. That was his offered opinion about himself, not my judgment. He asked me if I thought he should get into computers. I told him yes, and I hope he took my advice.

In Five-Card Draw, you raise with two pair before the draw. One pair, even aces, is too weak, especially since the opener must have at least jacks. Also, since you will draw three cards, you get a lot of information in the draw. Generally, the more information you expect to get in the future, the more you want to see it cheaply. That may sound counterintuitive, but it's true. With three of a kind or better, you typically want more people in the pot, and you want to disguise your strength. However, two pair is usually strong enough to win, but not strong enough to raise after the draw. If you want to make money with this hand, you have to do it early. And since you draw only one card, you have most of the information you're going to get about this hand. Since you probably know more about your final hand than the other players do about theirs, you want to force them to make decisions now. Of course, these are just general guidelines. Poker requires you to mix up your play so no one can guess your hand from your betting.

At that point, there were three small bets in the pot, plus the antes, and I had to put in two to call. That made calling nearly a break-even proposition. However, if I filled my hand, I could make additional money after the draw. If I didn't, I would just fold it. So it was an easy decision to stay in. Given my theory and experience to date, I expected Harrison to fold if I stayed in the hand. But unlike most straight and flush draw situations, I didn't mind further raises, since I would get two bets from Harrison and Jason for every one I had to put in, and my chances of winning were better than two to one. That logic wouldn't apply to a raise I made myself, since I expected it to be called only by Jason, and I didn't have better than an even chance of filling.

Nevertheless, you always consider raising. In poker, you need a good reason to call. When you're uncertain, you fold or raise. That's one of the essential lessons of the game. The safe, middle-class strategy is to take the intermediate course when you cannot evaluate the extremes; you make a strong decision only when you're confident it's right. To succeed in poker, you must be bold precisely when you're unsure of what's going on. The logic is that if you're uncertain, you should try to throw the other players off balance as well. Also, most money is made and lost in uncertain pots. If you're not going to be bold when the most money is at stake, you should find a different game.

A raise would cost me expected value, but it would represent my hand as three of a kind (the two pair rule applies when you are the first raiser; raising after one player has jacks or better and another has represented two pair requires a stronger hand). When I drew one card afterward, the raise would suggest instead that I had aces up. Of course, I could also have three of a kind with a kicker, or a straight or flush draw, but those are unlikely plays in this situation, especially against two bettors (remember, I was writing Harrison off, but I didn't think Jason knew that-you have to keep in mind what your actions look like to the other players). Bluffs are rarely constructed to be confusing; typically, a bluffer will tell a consistent tale. Four of a kind would cross Jason's mind, but it's too rare a dealt hand to consider. If you play poker to avoid losing to pat quads, you'll lose a lot of money on the other 99.97 percent of the hands. The upshot is that if I raised now and drew one card, Jason would probably think I had two pair, one of which was aces.

The advantage of this deception was that Jason would probably think he had been beaten if he didn't fill a full house on the draw. I could bet and probably win the pot. If he started with three of a kind, or filled a full house, he would check and collect an extra bet from me, in which case the strategy would cost me two bets. But all the other times, either I fill or Jason folds and the raise gets me at least one extra bet, sometimes the whole pot. Another advantage is that if Jason has a very strong hand and I fill, we will do some mutual raising after the draw. If I raise predraw, he'll put me on a full house; if I call, he'll think it is a straight or a flush. This will save me some money if he has a full house and I get the straight or flush; he will be afraid of my aces full. But it could cost me a lot more money if I fill my straight flush and he gets a full house.

These same general principles apply to most drawing hands, although, of course, the details differ. You should raise on some of them, but call on most. You should think about which of your opportunities are the best for this play. This one was cheaper than most because I had 19 chances of filling my hand, but it also had less potential profit. The deciding factor was that a raise hurt my situation if I got the straight flush, which could be a royal flush. If you get a royal flush, you owe it to yourself to get the most you can out of it. So I called.

Now came the first surprise. Harrison raised and Jason reraised. This was the first time two players had even called after I bet, and they both raised. Instantly, I reverted to my backup conspiracy theory. This looked like overt collusion. Either Harrison or Jason had signaled to the other a very strong hand, and they were acting in concert to push up the stakes.

Of course, nothing could have made me happier. I was contributing one-third of the additional chips to the pot, and I felt I had a 40 percent chance to win it. Each $1 that went into the pot was 74 in expected value in my pocket. It's true that there was a small chance Harrison or Jason had a straight or better, but even that worked in my favor. If it was true, I could make so much money if I filled my straight flush that it more than made up for the loss if I filled the straight or flush and lost to a full house. I could also make a lot beating a pat straight with a flush, or a pat flush with an ace high flush. Winning money is twice as sweet if the other players think they are cheating you.

The Draw

I called, doing my best to look like a guy who was doggedly pot committed. Now came another shock. Harrison announced that he was splitting his openers and drawing one card. This had not happened at the table yet. I had read the rules and knew the declaration was required, but I noticed a lot of rules were routinely ignored at the table (for example, losers of a showdown routinely threw their cards away without showing them, something that hurts a newcomer more than a regular since he doesn't know playing styles).

The predraw betting was much too strong to justify Harrison's staying in, let alone raising, on an ordinary flush or straight draw. It was too expensive if he didn't make it and might not win if he did. He couldn't have the bug because I did, and anyway I was just calling. But it doesn't make sense to break up a pair and draw one card for anything except a straight or flush draw.

It seemed morel ikely that Jason had passed Harrison a signal to open and raise, then fold after the draw. My guess was that Harrison didn't have openers and announced the split to divert suspicion. He could angrily muck his hand after the draw. But he had helped Jason suck additional money-my money-into the pot. Or so they thought. They didn't know about my royal flush!

Jason took one card, which was also puzzling. Two pair was far too weak to pass a signal for this kind of trick. I figured him for a high three of a kind. If you draw one card to three of a kind and a kicker, there are only four cards in the deck that can improve your hand (the one that matches your three of a kind and the three that match your kicker). If you draw two cards, you could get your fourth match on the first new card, and if you don't, you're in the same position as if you had kept a kicker. So you have one extra chance to improve. With me calling three raises, Jason would want all the insurance he could get. There was no possible deception value to the play. And there's no point to keeping a kicker because it's a high card-with a full house in draw poker, the rank of the pair is irrelevant (with community cards, as in Omaha or hold 'em, it matters a lot).

The one exception to this logic is holding an ace kicker because there are four cards that can pair it: the three aces plus the bug. In that case, you have exactly the same 5/48 (10 percent) chance of improving by drawing one or two. It's still slightly better to draw two, because you have more chance of getting four of a kind instead of a full house, but that very rarely makes a difference. So I figured Jason for a high three of a kind plus an ace. That was bad in the sense that he had at least 1, and maybe 4, of the 19 cards I needed to fill. But it was good in that I was holding at least 1, and maybe 2, of the 5 cards he needed. On a relative basis, I did him more damage than he did me.

Jason's draw also eliminated almost all the possibilities that he had been dealt a hand that could beat a straight or flush. Four of a kind was the only remaining possibility. It wasn't totally out of the question, but it was unlikely enough to be a minor factor in calculations. I drew one card and got a king. There went my dreams of a royal flush confounding and bankrupting the cheaters with their four of a kind.

Harrison and Jason both checked. This was more confusing, but I didn't care. There was little point to raising, and none to folding. So I checked. Harrison had three sevens; Jason had a busted flush. Jason looked at my hand and called loudly but calmly for the floorman.

Harrison's declaration of splitting openers had been pure misdirection. He had been dealt three sevens and the queen. When Jason raised and I called, he figured Jason for two pair and me for two pair or three of a kind. He liked his chances enough to raise, but when Jason reraised and I called, he figured he was probably beaten. Since he was planning to take one card anyway, announcing he was splitting openers made it less likely that either Jason or I would bet after the draw, in fear that he had filled his straight or flush and was planning a check-raise. That did in fact occur, although given our draws, Harrison would have chased us out with any bet at all. Jason's two raises were normal poker misdirection; he was betting a flush draw like two pair.

Jason said Harrison's declaration of splitting was illegal. He insisted that Harrison's hand was dead and the pot belonged to me. Harrison argued the poker adage that "talk doesn't matter." After each had stated his case calmly, the floorman asked if I wanted to say anything. I didn'tJason had put things clearly and I didn't know the house convention on the subject. Harrison turned up his discard (it was a five). The floorman awarded me the pot.

I had a little trouble fitting this into my conspiracy theory, unless Jason was trying to gain my confidence in order to sell me the Brooklyn Bridge. I don't know if the game changed after that, or just my perception of it, but we seemed to be playing normal poker. Jason left about an hour later, with no offer of a bridge nor any attempt to get my last name, and new players sat down. I went up and down for the next few hours, never again reaching the peak after my disputed victory. I left about two o'clock in the morning, ahead for the night. Tom left only reluctantlymaybe he really was a regular.

CHAPTER 6

Дата добавления: 2015-10-26; просмотров: 173 | Нарушение авторских прав

| <== предыдущая страница | | | следующая страница ==> |

| ADVENTURERS AND PLANTERS | | | A TALL, BOLD SLUGGER SET VIVID AGAINST THE LITTLE, SOFT CITIES |