|

Читайте также: |

Thus, selfhood is something independent, because one can retain the sense of ownership yet lose the sense of agency. But can one also hallucinate agency? The answer is yes — and, oddly, many consciousness philosophers have long ignored this phenomenon. You can have the robust, conscious experience of having intended an action even if this wasn’t the case. By directly stimulating the brain, we can trigger not only the execution of a bodily movement but also the conscious experience of having the urge to perform that movement. We can experimentally induce the conscious experience of will.

Here’s an example. Stéphane Kremer and his colleagues at the University Hospital of Strasbourg stimulated a specific brain region (the ventral bank of the anterior cingulate sulcus) in a female patient with medically intractable epileptic seizures, in order to locate the epileptogenic zone before performing surgery. In this case, the stimulation caused rapid eye movements scanning both sides of the visual field. The patient began to search for the nearest object she could grasp, and the arm that was opposite the stimulated side — her left arm — began to wander to the right. She reported a strong “urge to grasp,” which she was unable to control. As soon as she saw a potential target object, her left hand moved toward it and seized it. On the level of her conscious experience, the irrepressible urge to grasp the object started and ended with the stimulation of her brain. This much is clear: Whatever else the conscious experience of will may be, it seems to be something that can be turned on and off with the help of a small electrical current from an electrode in the brain.7

But there are also ways of elegantly inducing the experience of agency by purely psychological means. In the 1990s at the University of Virginia, psychologists Daniel M. Wegner and Thalia Wheatley investigated the necessary and sufficient conditions for “the experience of conscious will” with the help of an ingenious experiment. In a study they dubbed “I Spy,” they led subjects to experience a causal link between a thought and an action, managing to induce the feeling in their subjects that the subjects had willfully performed an action even though the action had in fact been performed by someone else.8

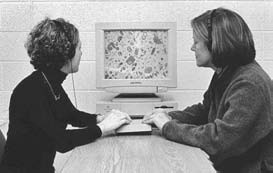

Each subject was paired with a confederate, who posed as another subject. They sat at a table across from each other and were asked to place their fingertips on a little square board mounted on a computer mouse, enabling them to move the mouse together, Ouija-board style. On a computer screen visible to both was a photograph from a children’s book showing some fifty objects (plastic dinosaurs, cars, swans, and so on).

The real subject and the confederate both wore headphones, and it was explained to them that this was an experiment meant to “investigate people’s feelings of intention for acts and how these feelings come and go.” They were told to move the mouse around the computer screen for thirty seconds or so while listening to separate audio tracks containing random words — some of which would refer to one or another object on the screen — along with ten-second intervals of music. The words on each track would be different, but the timing of the music would be the same. When they heard the music, they were to stop the mouse on an object after a few seconds and “rate each stop they made for personal intentionality.” Unknown to the subject, however, the confederate did not hear any words or music at all but instead received instructions from the experimenters to perform particular movements. For four of the twenty or thirty trials, the confederate was told to stop the mouse on a particular object (each time a different one); these forced stops were made to occur within the prescribed musical interval and at various times after the subject had heard the corresponding word over her headphones (“swan,” say).9

Figure 15: Hallucinated agency. How to make subjects think they initiated a movement they never intended. Figure courtesy of Daniel Wegner.

According to the subjects’ ratings, there was a general tendency to perceive the forced stops as intended. The ratings were highest when the corresponding word occurred between one and five seconds before the stop. Based on these findings, Wegner and Wheatley suggest that the phenomenal experience of will, or mental causation, is governed by three principles: The principle of exclusivity holds that the subject’s thought should be the only introspectively available cause of action; the principle of consistency holds that the subjective intention should be consistent with the action; and the principle of priority holds that the thought should precede the action “in a timely manner.”10

The social context and the long-term experience of being an agent of course contribute to creating the sense of agency. One might suspect that the sense of agency is only a subjective appearance, a swift reconstruction after the act; still, today’s best cognitive neuroscience of the conscious will shows that it is also a preconstruction. 11 Experiencing yourself as a willing agent has much to do with, as it were, introspectively peeping into the middle of a long processing chain in your brain. This chain leads from certain preparatory processes that might be described as “assembling a motor command” to the feedback you get from perceiving your movements. Patrick Haggard, of University College London, perhaps the leading researcher in the fascinating and somewhat frightening new field of research into agency and the self, has demonstrated that our conscious awareness of movement is not generated by the execution of ready-made motor commands; instead, it is shaped by preparatory processes in the premotor system of the brain. Various experiments show that our awareness of intention is closely related to the specification of which movements we want to make. When the brain simulates alternative possibilities — say, of reaching for a particular object — the conscious experience of intention seems to be directly related to the selection of a specific movement. That is, the awareness of movement is associated not so much with the actual execution as with an earlier brain stage: the process of preparing a movement by assembling different parts of it into a coherent whole — a motor gestalt, as it were.

Haggard points out that the awareness of intention and the awareness of movement are conceptually distinct, but he speculates that they must derive from a single processing stage in the motor pathway. It looks as though our access to the ongoing motor-processing in our brains is extremely restricted; awareness is limited to a very narrow window of premotor activity, an intermediate phase of a longer process. If Haggard is right, then the sense of agency, the conscious experience of being someone who acts, results from the process of binding the awareness of intention together with the representation of one’s actual movements. This also suggests what subjective awareness of intention is good for: It can detect potential mismatches with events occurring in the world outside the brain.

Whatever the precise technical details turn out to be, we are now beginning to see what the conscious experience of agency is and how to explain its evolutionary function. The conscious experience of will and of agency allows an organism to own the subpersonal processes in its brain responsible for the selection of action goals, the construction of specific movement patterns, and the control of feedback from the body. When this sense of agency evolved in human beings, some of the stages in the immensely complex causal network in our brains were raised to the level of global availability. Now we could attend to them, think about them, and possibly even interrupt them. For the first time, we could experience ourselves as beings with goals, and we could use internal representations of these goals to control our bodies. For the first time, we could form an internal image of ourselves as able to fulfill certain needs by choosing an optimal route. Moreover, conceiving of ourselves as autonomous agents enabled us to discover that other beings in our environment probably were agents, too, who had goals of their own. But I must postpone this analysis of the social dimension of the self for a while and turn to a classical problem of philosophy of mind: the freedom of the will.

Дата добавления: 2015-10-31; просмотров: 166 | Нарушение авторских прав

| <== предыдущая страница | | | следующая страница ==> |

| THE ALIEN HAND | | | HOW FREE ARE WE? |