Social scientists and students from the University of Arizona studied people's spending and eating habits by examining household garbage left out on the street (Rathje, 1974; Zorn, 1988). Sociolo-

gists Joan Luxenburg and Lloyd Klein (1984) monitored citizens' band radio broadcasts near a truck stop in Oklahoma to learn about a relatively new form of soliciting lor prostitution. These are two of the unconventional examples of the use of unobtrusive measures in social scientific research. Unobtrusive measures include a variety of research techniques that have no impact on who or what is being studied. They are designed as nonre-active, since people's behavior is not influenced. As an example, Emile Durkheim's statistical anal-

|

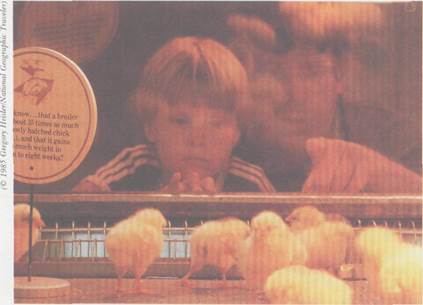

An unobtrusive measure was used to determine the most "popular" exhibit at the massive Museum of Science and Industry in Chicago. By looking at maintenance records, museum officials learned that the floor tiles surrounding the chicken-hatching exhibit were worn out fastest — an indirect measure of the millions of people who stood before this fascinating display each year.

PART ONE ♦ THE SOCIOLOGICAL PERSPECTIVE

ysis of suicide neither increased nor decreased human self-destruction. Whereas subjects of an experiment are often aware they they are being watched—an awareness that can influence their behavior—this is not the case when unobtrusive measures arc used. Consequently, sociologists can avoid the Hawthorne effect by employing unobtrusive methods (Van Maanen, 1982; Webb et al., 1981; see also B. Berg, 1989).

ysis of suicide neither increased nor decreased human self-destruction. Whereas subjects of an experiment are often aware they they are being watched—an awareness that can influence their behavior—this is not the case when unobtrusive measures arc used. Consequently, sociologists can avoid the Hawthorne effect by employing unobtrusive methods (Van Maanen, 1982; Webb et al., 1981; see also B. Berg, 1989).

One basic technique of unobtrusive measurement is the use of statistics, as in Durkheim's work. Crime statistics, census data, budgets of public agencies, and other archival data are all readily available to the sociologist. Much of this information can be obtained at relatively low cost. However, if the researcher is forced to rely on data collected by someone else, he or she may not find exactly what is needed. For example, researchers studying family violence can use statistics from police and social service agencies on reported cases of spouse abuse and child abuse. Yet such government bodies have no precise data on all cases of abuse.

Many social scientists find it useful to study cultural, economic, and political documents, including newspapers, periodicals, radio and television tapes, scripts, diaries, songs, folklore, and legal papers, to name a few examples. In examining these sources, researchers employ a technique known as content analysis, which is the systematic coding and objective recording of data, guided by some rationale.

Suppose you were interested in studying the treatment of women in American society. In pursuing this topic, sociologist Carol Auster (1985) did a content analysis of Cirl Scout handbooks from 1913 to 1984. She found dramatic changes over time in the organization's view of proper roles and career aspirations for women. For example, a "laundress" merit badge of 1917 had given way to an aerospace badge by 1980. Early advice such as "none of us like women who ape men" had been replaced by guidelines reflecting less traditional and stereotypical views of men and women. Conflict theorists have often found such research techniques useful in detecting how the media portray women in a negative manner. In another use of content analysis, Deborah Chavez (1985) found that men in comic strips far outnumber women. Indeed, women are main characters only 15 percent of the time. And half

of all male characters in comic strips but only 4 percent of female characters are shown as employed.

Content analysis is typically viewed as useful in studying print media such as newspapers, magazines, and books. However, this technique of unobtrusive measurement can also be employed in studying the content of movies, television programs, or videos. As an example, sociologists Richard Baxter, Cynthia De Riemer, Ann Lan-dini, Larry Leslie, and Michael Singletary (1985) conducted a content analysis of 62 Music Television videos in 23 content categories. Frequent occurrences were found in the categories of visual abstraction, sex, dance, violence, and crime. The researchers (1985:339) conclude that "music video sexual content may have a decidedly adolescent orientation, suited to its audience; fantasy exceeds experience and sexual expression centers primarily on attracting the opposite sex" (see also Denisoff, 1988).

Social scientists find that unobtrusive measures can be quite helpful in pursuing certain topics that cannot easily be studied using other methods. What if you wished to investigate the attitudes of Soviet Communist party leaders toward workers' movements in eastern Europe? It might be impossible to arrange interviews with Soviet leaders, and they would hardly allow you to sit in on meetings of the Politburo (the ruling body of the Communist party). But you could do a content analysis of articles in Pravda, the official publication of the party. This method of research might not be ideal, yet it might be the only realistic option.

Unobtrusive measures have also proved to be valuable as a supplement to other research methods. For example, one investigator wished to examine the relationship between reported and actual beer consumption. He obtained a "front door" measure of consumption by asking residents of houses how much beer they drank each week. At the same time, a "backdoor" measure was developed by counting the number of beer cans in their garbage. This backdoor measure produced a considerably higher estimate of beer consumption (Rathje and Hughes, 1975; Webb et al., 1981:17-18).

It is important to realize that research designs need not be viewed as mutually exclusive. As was

CHAPTER TWO ♦ METHODS OF

SOCIOLOGICAL RESEARCH

BOX ♦ 2-2

CURRENT RESEARCH

UNDERSTANDING TABLES AND GRAPHS

|

| T |

ables allow social scientists to summarize data and make it easier for them to develop conclusions. A cross-tabulation is a type of table that illustrates the relationship between two or more characteristics. During 1987, the Gallup organization polled 1005 Americans, ages 18 and over, regarding the issue of sex discrimination by private clubs. Each was interviewed and asked: "Do you think that private clubs should or should not have the right to exclude prospective members on the basis of their sex?" There is no way that, without some type of summary, analysts in the Gallup organization could examine hundreds of individual responses and reach firm conclusions. However, through use of the cross-tabulation presented in the accompanying table, we can quickly see that women object more frequently than men to any such exclusion on the basis of gender.

Graphs, like tables, can be quite useful for sociologists. The accompanying illustration is an example of a graph known as a pictograph.

Pictographs use symbols to show the relationship between different characteristics.

The illustration here shows that in 1985 the state of Alaska spent about four times as much per pupil on elementary and secondary education as Mississippi did. However, this pictograph relies on a visual misrepresentation. Through use of two dimensions—length and width—the graph inflates the size of the expenditure level for Alaska. Although it should appear about 4 times as large as the Mississippi level, the Alaskan money bag actually appears about 16 times as large. Thus, the graph misleads readers as to the comparative spending levels of the two states.

This example underscores the fact that tables and graphs can be easily misunderstood and can even be deceptive. If you are reading a table, be sure to study carefully the title, the labels for variables, and any footnotes. If you are examining a pictograph, check to see if the visual representations seem to reflect accurately the statistics being illustrated (Fitzgerald and Cox, 1984; Huff, 1954:69).

Дата добавления: 2015-08-27; просмотров: 74 | Нарушение авторских прав

| <== предыдущая страница | | | следующая страница ==> |

| Surveys | | | Mississippi $2128 |