Asian economies

Asia’s great moderation

Some of the world’s stablest economies are Asian. Time to worry?

Nov 10th 2012 | HONG KONG | from the print edition

LAOS, a poor country of 6m people wedged between Vietnam and Thailand, has no openings to the sea and few routes to world attention. But it is now enjoying a rare moment in the sun. Last month it won approval to join the World Trade Organisation. This week it hosted the ninth Asia-Europe meeting, which brings together leaders from the world’s most and least dynamic regions. Its small economy, which exports gold, copper and hydropower, is distinguishing itself. Its growth rate is not only one of the fastest in the world but also one of the steadiest.

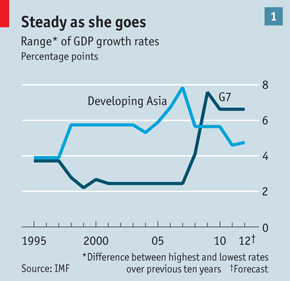

From 2002 to 2011 growth fluctuated within a remarkably narrow range, never falling below 6.2% and never rising above 8.7%. Only three countries have recorded a steadier growth rate (as measured by its standard deviation) over that period. Two of them are also Asian: Indonesia and Bangladesh. Growth in developing Asia is now steadier, as well as faster, than growth in the “mature” economies of the G7 (see chart 1). It was more stable in 2002-11 than over any other ten-year span since 1988-97.

The “Great Moderation” is the name given to the era of economic tranquillity that prevailed in America and elsewhere in the rich world before the financial crisis. Should the label now be applied to Asia?

Asia’s economies are better known for their speed than their stability. From 1996 to 1998, for example, growth in five big South-East Asian countries (Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, Thailand and Vietnam) swung from 7.5% to minus 8.3% as the Asian financial crisis struck. Even now some highly open economies, such as Thailand, Singapore and Taiwan, remain more volatile than the global average. Exposed to international trade flows, their industrial output fluctuates like a twirling ribbon with every twitch of demand.

But developing Asia (which excludes rich economies like Hong Kong, Singapore, South Korea and Taiwan) is dominated by populous countries that rely increasingly on domestic demand to drive their economies. Household consumption contributed half of the growth of just over 6% Indonesia enjoyed in the year to the third quarter (its eighth consecutive quarter of growth at that pace). Exports have fallen from about 35% of GDP ten years ago to less than a quarter in 2011. Developing Asia’s combined current-account surplus, which reflects its dependence on foreign demand, more than halved from 2008 to 2011 and is expected to fall further this year.

Asia’s stability also owes something to demand management. During the Asian financial crisis policymakers faced a dilemma. They could defend their exchange rates by raising interest rates. But that would cripple borrowers. Or they could let their currencies fall and ease rates. But that would inflate the burden of foreign-currency debt, crippling borrowers too.

In the aftermath of the crisis the region worked its way out of this trap. Most countries accumulated an impressive stock of hard-currency reserves and weaned themselves off foreign-bank loans in favour of foreign equity and local-currency bonds. Because these liabilities were denominated in their own currency, they did not rise in value when the currency fell.

That has freed policymakers to cut interest rates when the economy slows. Indonesia’s central bank, for example, slashed rates by three percentage points from December 2008 to August 2009. It cut rates by another point from October 2011 to February 2012. Thanks in part to its responsive central bank, Indonesia’s year-on-year growth rates over the past 20 quarters have been the most stable in the world.

Wise monetary policy was also one of the reasons cited for the Great Moderation enjoyed by the G7 economies. Another was the supposed depth and sophistication of the rich world’s financial systems, which, it was said, allowed households to smooth their spending, firms to diversify their borrowing and banks to unburden their balance-sheets. Both of these pillars of stability proved false comforts. Economists had not quite settled on an explanation for the Great Moderation before it inconveniently ceased to exist.

Worryingly, Asia’s great moderation has also been accompanied by sharply rising credit. According to Fred Neumann of HSBC, leverage is now higher than at any time since the Asian financial crisis (see chart 2). This credit expansion may represent healthy “financial deepening”, which many economists believe is a cause of growth and stability. But rising leverage can also be a threat to stability. The late Hyman Minsky, among others, argued that drops in volatility allow firms and households to borrow more of the money they invest. Stability, in Minsky’s formulation, eventually becomes destabilising. Overleverage does not require excessive optimism, merely excessive certitude; not fast growth, merely steady growth.

Fortunately, Asia’s policymakers never shared the West’s faith in self-correcting financial systems. The region has pioneered “macroprudential” regulations, designed to curb excessive credit and capital flows even without raising interest rates. In March, for example, Indonesia tightened loan-to-value ratios on mortgages and imposed minimum downpayments on car and motorbike loans.

Mr Neumann is, however, sceptical that regulatory tightening can substitute for the monetary kind. Macroprudential controls are not watertight, he notes. As long as capital remains cheap, money will leak. If the regulator lowers mortgage loan-to-value ratios, for example, banks may simply raise the appraised value of a home. If regulators impede foreign purchases of property, as Hong Kong just did, foreigners will seek inventive ways around the rules.

Hong Kong’s freedom to raise rates is constrained by its currency’s fixed link to the dollar, one of the few pegs to survive the Asian financial crisis. Other central banks do not have that excuse. Currency flexibility has given them the freedom to cut rates when growth slows. It should also allow them to raise rates when financial excess threatens—even if rates remain near zero in America, Europe and Japan. If stable growth allows lenders or borrowers to become overstretched, it can “sow the seeds of its own destruction”, Mr Neumann argues. Nothing great about that.

Дата добавления: 2015-08-21; просмотров: 93 | Нарушение авторских прав

| <== предыдущая страница | | | следующая страница ==> |

| Исторические заметки | | | Хоркунова Н.В. |