Читайте также:

|

Then, in the summer of 2007, searchers unearthed a second shallow pit containing several dozen charred bone fragments, teeth, and a scrap of cloth similar to the sailor-style undergarments Aleksei favored. It now appears that Yurovsky’s story about burning two bodies was not a ruse after all; DNA tests have shown these fragments are almost certainly the remains of the tsarevich Aleksei and his sister. The same series of tests also revealed that Skeleton Number 6, one of the three grand duchesses in the original grave, was indeed a carrier of type B hemophilia.

The Imperial Family, 1913 (Courtesy of Kelly Wright)

Maria, Tatiana, Anastasia, and Olga, 1914 (Marlene A. Eilers Koenig collection)

Tsar Nicholas II and his children at Stavka, 1916

(General collection, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University)

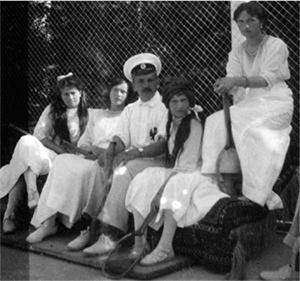

The grand duchesses resting between tennis matches with an officer, 1914

(General collection, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University)

The Big Pair working in the lazaret, 1914 (General collection, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University)

The Little Pair posing in the wards, 1914 (General collection, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University)

Tatiana, Anastasia, and Ortipo, photographed by Maria in June 1917 (Courtesy of Kori Lawrence)

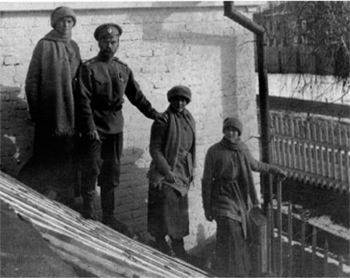

Olga, Nicholas, Anastasia, and Tatiana on the greenhouse roof at Tobolsk, 1918 (General collection, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University)

AUTHOR’S NOTE

For over ninety years, studying the history of the last tsar and his family has been a murky, mine-filled proposition. Opinions vary widely, and tempers run high. Fans and historians alike argue over whether Tsar Nicholas II was a malleable despot or a mild-mannered daddy. Was Alexandra a hysterical religious fanatic or a painfully shy woman afflicted with anxiety disorders? Depending on who you ask, their five children might have been angels or hooligans. From violently anti-Semitic Soviet tracts to the moistly sentimental memoirs of friends and courtiers, there is plenty to sort and sift. Where the Romanovs’ captivity and execution are concerned, myths and misremembrances sometimes snowball into outright lies, and contradictions abound.

Fortunately, the Bolsheviks preserved mountains of the imperial family’s letters, diaries, and photographs, though the Soviets kept the archives sealed for decades. With the fall of the USSR, however, the personal documents of the last tsar’s family began to trickle, then flood, from behind closed doors.

As often as possible, I relied on those documents and photographs, which number in the hundreds of thousands, to guide me. When that proved impossible, I turned to memoirs of the people who shared the Romanovs’ final years, particularly favoring those who wrote down their impressions as events unfolded. Even then, the testimony of firsthand witnesses diverged time and again. What’s an author to do?

In the end, I trusted my own collective impressions of my characters. Aside from the inevitable jiggling of the chronology inherent in fiction, I occasionally made choices to best serve my story, but only when the history itself provided no clear hints. Specifically:

OTMA and Politics

It is impossible to know how much the Romanov children understood about the revolution, or the danger their family faced under captivity. None of the grand duchesses’ post-revolutionary diaries have survived, yet the fact that Maria and Anastasia burned their 1918 diaries before being transferred to Ekaterinburg perhaps speaks for itself. At the very least, the children were aware of the news headlines, and I don’t believe they could have been immune to the tension mounting in the Ipatiev house in late June and early July. Even so, I have very likely portrayed them as more informed than they actually were. On the whole, their lives were sheltered, and their education lackluster. Their contemplation and experience of the world outside the imperial parks and palaces was limited. Captivity didn’t change that fact. To some observers, the Little Pair seemed content and more or less oblivious in Tobolsk. Olga, however, has gained a reputation for being sensitive, insightful, and perceptive. Although I think that’s an exaggeration and do not believe she was especially gifted, I have nonetheless made use of that view of Olga in service to my story. While there is some evidence to suggest that Olga and Tatiana were more aware of the family’s peril than their younger siblings, I myself don’t believe Olga had any reason to suspect they would all be executed.

Rasputin

Did he truly have healing powers? No one knows. Some scholars believe he used hypnosis to soothe the tsarevich, while others claim his “powers” were well-timed coincidences. Ultimately, it doesn’t matter. A story told through the eyes of the imperial family can only show what the Romanovs themselves believed: that Grigori Rasputin healed Aleksei through the power of prayer. Traditionally Rasputin has held a vivid reputation as a drinker and a womanizer. At the time of his murder, the majority of Russians believed he was a demon who possessed the empress, made vulgar public displays, and meddled in politics. Yet to the imperial family, he showed nothing but virtue. Which of these two extremes is closer to the truth? Again, for my story it doesn’t matter— whether they were true or not, the gossip and rumors were enough to destroy Rasputin in the end, and with him, the Romanov dynasty.

Russian Nicknames

Although Russians consider it stiff and formal to call close friends and relations by given names, at first glance the family of Nicholas II seems to be an exception. While they had dozens of cloying pet names—Wify, Huzzy, Boysy, Sunny, Sunbeam, Baby, girlies, etc.—their letters and diaries show almost no trace of traditional Russian diminutives. Privately, Nicholas and Alexandra favored English nicknames for each other: Nicky and Alix rather than Kolya and Shura. As for the children, I’ve found a scant handful of letters in which the empress refers to three of her daughters as Olenka, Tatianochka, and Mashenka. Even the children addressed and signed their letters and notes among themselves with their given names—though once in a while Anastasia closed a letter with “Nastasya” or “Nastaska.” Only Maria Nikolaevna stands out from the pattern for being routinely called Mashka by her sisters.

In spite of the documentary evidence, the Romanovs considered themselves quintessentially Russian, so chances are slim that they would have ignored this ingrained facet of Russian culture. The imperial children spoke Russian among themselves as well as with their father, so although I can’t prove it, I believe it’s almost certain they used the expected diminutives—Olya, Nastya, Alyosha—when speaking to one another. As a compromise, I reserved those nicknames for moments of tenderness or stress. I should also admit that Tanya is a far more common diminutive for Tatiana than Tatya. I chose Tatya because I like the sound of it, and because I do know that the imperial children addressed Tatiana Botkin as Tanya, and I wanted to avoid confusion.

In the west, Anastasia’s nickname, Shvybzik, is commonly believed to mean “imp” in Russian. It doesn’t. In fact, it means nothing at all in Russian. Instead, it seems the imperial family adopted a German word, schwipsig (meaning “tipsy”), to describe their impish prankster, altering the pronunciation in the process.

Дата добавления: 2015-10-31; просмотров: 91 | Нарушение авторских прав

| <== предыдущая страница | | | следующая страница ==> |

| AUTHOR’S NOTE 20 страница | | | SELECTED BIBLIOGRAPHY |