|

Читайте также: |

I’ve had and still have problems in which I get involved for no reason, caused rather by the lack of reasons and by Balkan fatalism. Every year or two I’m obliged to clean the stable and I suffer. After three months in Aldo’s company, Saul tried to get down to work, but he didn’t find it easy. Aldo was there from November 1953 to the end of March 1954, and most of the time passed in a re-creation of their carefree student lives, only this time they had a lot more money with which to do it. They played billiards, but on Steinberg’s private table, whenever they wanted and without having to wait their turn in a public bar. They did not have to be content with reading about boxing matches in the newspapers as they had done on long-ago lazy afternoons in Il Grillo; now they went to the arenas and sat in the best seats. If they wanted to see two movies on a single day, interspersed with a good meal in a chic restaurant, they did it. They saw Broadway plays and heard Toscanini conduct the New York Philharmonic. Just for fun, they were among the first flyers on New York Airways, “the first scheduled helicopter passenger service in the world.” And when they traveled throughout the southern states, they flew to major cities, rented comfortable cars, and stayed in the best hotels. They were fascinated with what they saw in the Jim Crow South and read some of the novels of William Faulkner while they were there. Seeing segregation at first hand was a shocking reminder of Steinberg’s life in Europe before the war and marked the beginning of his interest in civil rights and his later quiet activism on behalf of African-American causes.

Aldo’s departure left him at loose ends. Steinberg had hardly worked at all during the visit, other than to choose drawings for his new book, The Passport, often amusing himself by dipping his fingertips in ink and using the prints as faces. When he bought a fingerprint kit to make the process slightly neater and cleaner, it was the only work-connected event significant enough to record in his daily diary. He had selected the book’s title and most of the content well before Aldo arrived, so he had a fairly firm idea of how he wanted it to look. He gave 241 drawings to the publisher, Harper & Brothers, and envisioned a book of 160 pages, which was more than they wanted or could use, but he was insistent, offering a halfhearted apology that there was “too much stuff in it but it’s too late to change.” Actually, he wanted to include more drawings, but he was unable to focus on selecting them, so he put the book aside to oversee the last-minute details of an exhibition at the Dallas Museum of Fine Arts. As he was so unsettled, he decided to go to the opening. He was not closely involved in the show, because it was the same exhibition that had originated at the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts and would go after Dallas to the Corcoran Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C. All he needed to do was to specify the order in which he wanted the works hung and then affix prices, in this case ranging from $250 to $500.

When he returned to New York, he could not avoid The Passport any longer, so he selected forty-nine additional drawings and sent them to his editor, Simon Michael “Mike” Bessie. Steinberg didn’t like conflict of any kind, even genteel discussions about how to arrange the drawings or which could legitimately be cut, so he didn’t stay around long enough to settle anything over one of the lavish lunches arranged by his Francophile, bon vivant editor. He was delighted to have a valid excuse to leave New York when Life magazine invited him to spend several weeks covering the Milwaukee Braves baseball team. However, before he could do this, he had to learn what “America’s pastime” was all about, and he needed to educate himself fast.

STEINBERG HAD BEEN TRYING TO UNDERSTAND American culture and society from the first day he set foot on American soil. From the bus that took him to New York from Miami, to the cross-country trips by bus, train, and car, to the Alaskan cruise he took with Hedda and the journey to the Deep South with Aldo, he had been eager to see everything, to bring his memories and souvenirs home with him, and to turn them into trenchant observations in drawings that inspired a shock of recognition in everyone who saw them.

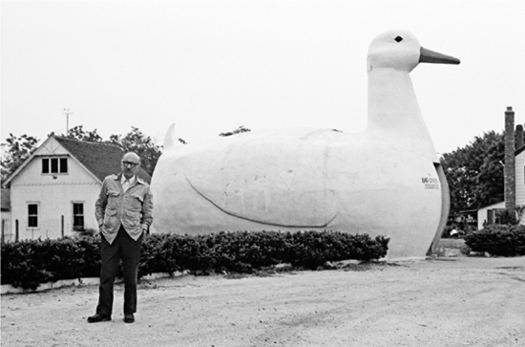

He expressed his interest in all things American through his personal library, which grew to include histories of the United States (particularly of the Civil War) and iconic fiction ranging from Melville, Poe, and Mark Twain to Theodore Dreiser, James T. Farrell, John P. Marquand, and John Dos Passos. After every trip his postcard collection burgeoned with photos of everything from county courthouses to Civil War monuments, motel cabins, fast-food stands built in the shape of foods they sold (the Long Island Duck was a leading example of the genre), wild animals in zoos, pinup girls, the Rocky Mountains, Niagara Falls, and even the Pennsylvania Turnpike.

Steinberg at the Long Island Duck. (illustration credit 16.1)

Steinberg at the Long Island Duck. (illustration credit 16.1)

“Whoever wants to know the heart and mind of America had better learn baseball,” said the cultural critic Jacques Barzun, but sports, particularly organized sports, was probably the only aspect of American life that Steinberg had not yet investigated; with the exception of boxing (which he had learned to like in Italy), he knew nothing about any of them. When he told this to Dorothy Seiberling, the art editor of Life, she told the journalist Clay Felker that they had to take Steinberg to Yankee Stadium. As the game progressed, they tried to explain to their befuddled guest what was happening on the field, and when it was over, they asked what he thought of it. “It just confirmed my suspicions,” he replied, leaving them to ponder “a remark that remains to this day undecoded.”

The first thing he did on his own after accepting the Milwaukee assignment was to walk over to his favorite newsstand on Lexington Avenue and buy every sports magazine and baseball manual, and all the daily newspapers just so he could read the sports pages for the first time ever. He took them home, spread them out, and studied them. Every so often Hedda could hear him muttering to himself in Italian, then repeating words and phrases in English. When a game was broadcast on television he would sit without moving, staring intently at the screen and repeating words after the announcers: “A called third strike … a line drive down the right field line …” All of this remained a foreign language to Hedda, while to him it became a familiar part of American English. When the game was over, he would consult his ever-growing stash of baseball magazines to look up biographies and statistics for the players whose names he had heard that day. He even taught himself how to score a game and often exclaimed out loud as he wrote the symbols for the player who got on first base with a bunt and the one who stole second.

When he joined the Braves in Philadelphia for the road trip, he had picked up enough of a vocabulary to be able to talk to the players in their own jargon, but he mostly kept silent, just as he had done when he was first in the navy and watched how other officers behaved so he could imitate their actions. The players were intrigued by the little man whose sketches captured the intensity of the game as well as its languor, and they were soon kidding around with him as they saw themselves take shape through his eyes. For Steinberg, baseball was all about “an incredible individual spirit done in a loosely collective manner.” His pitcher stares down from the mound with the menacing intensity of a high-speed locomotive bearing down on a hapless batter, while his catcher is an immovable object, a formidable block confident of receiving the pitch. The batter poises on his toes like a gymnast ready to take off in an arabesque of movement. A drawing of the entire team mimics the annual group photograph for which every team in every league poses, and here Steinberg’s players have indistinguishable faces as they cluster around the glowering figure of the manager, who hunkers down at their center. A baseball diamond floats like an oversized halo just above their heads, while in front of this tableau, a bat and ball lie crossed on the ground with two tiny trophies on either side, a loving cup and a figure on a pedestal.

The players took to the guy with the funny accent, thick black-framed glasses, and sliver of a mustache, who came to the dugout each day in bespoke or Brooks Brothers clothes and hand-sewn shoes. They gave him a baseball hat and jacket, boldly emblazoned with the Milwaukee Braves logo, and he wore them proudly for the rest of his life, especially when he watched a game alone at home. For Steinberg, baseball became “an allegorical play about America, a poetic, complex, and subtle play of courage, fear, good luck, mistakes, patience about fate and sober self-esteem (batting average).” He agreed with Barzun that it was “impossible to understand America without a thorough knowledge of baseball.”

ONCE THE LIFE ASSIGNMENT WAS COMPLETED, it was June and well past time to get down to the business of earning money. For the past several years, because Saul had been away so much, Hedda had decided on her own where they would vacation, usually renting a house from one of their many friends in Wellfleet, Cape Cod, with Saul joining her when he could. This summer he needed to work with Jerome Robbins on stage sets for a new ballet, so she decided to rent a house in Stonington, the Connecticut town where Robbins summered along with a collection of New Yorkers that included the poet James Merrill, who soon became Hedda and Saul’s good friend as well. They both wanted to buy a country house and were still thinking primarily of Cape Cod, but because Saul had so many commissions to fulfill, Connecticut now seemed a more reasonable distance from New York than the Cape. They decided to see if they liked it by renting a house big enough for each to work in comfortably. Hedda set up her studio and painted while Saul spent most of his days at Robbins’s house, informing himself about the ballet that became The Concert. He executed two backdrops, painted curtains that featured some of the same creatures and characters that populated his work for The New Yorker, in front of which the dancers played out the dance in costumes that reflected those characters. The Concert became one of Robbins’s most successful creations and was responsible for many in the steady stream of requests for Steinberg to work in film and theater.

Working with Robbins provided a fun-filled diversion when Steinberg compared it to his other commitments, which at this time could be divided into two large categories: moneymaking commercial projects and dealing with his ever-growing fan mail. It had been nine years since he sold his first cover to The New Yorker, and cognizant of Geraghty’s concern for his slipping status at the magazine, he worked hard to get another. When it appeared, on March 20, it caused a sensation. For the next several months letters poured in, all similar to one written by a truck driver who delivered the magazine to subscribers in Salmon Falls, New York. “What the hell does this cover mean?” he demanded, referring to the black ink drawing of a tall mustached cat whose face resembles Steinberg’s and who stands on two feet and holds a smaller cat in his arms while two others cluster at his feet. The staff writer who answered the letter gave its writer and most of the others who asked similar questions the same reply: “Our March 20 cover has no hidden meaning. It is simply Saul Steinberg’s version of the standard, old-fashioned portrait of a father and children.”

Steinberg in his Milwaukee Braves uniform. (illustration credit 16.2)

Steinberg in his Milwaukee Braves uniform. (illustration credit 16.2)

Steinberg read his fan mail carefully and kept all of it, both positive and negative, but he seldom responded unless it came from children, whose innocent yet penetrating questions and comments he could not resist. A nine-year-old from Brooklyn wrote to tell him how much he liked a picture of “baby shore birds” that he saw when his father took him to the Janis gallery. He wanted to buy it but was told it cost $200. The boy wrote that he counted forty-eight birds in total, which would make each bird worth about four dollars. “I have $20 saved up,” he wrote, and asked Steinberg to make a drawing he could afford to buy, one with five birds. A week later the astonished little boy wrote a second letter, this time to thank Steinberg for “the lovely present” of birds that looked “just like sandpipers,” made from fingerprints, ink, and crayon. In a postscript he wrote that he was sending a picture of birds he had drawn himself to thank the artist.

Unfortunately, the majority of letters Steinberg had to deal with were not as pleasant. Many kept his lawyer busy, for he was highly litigious and always on the lookout for possible infringement of his intellectual property rights. He wanted to sue the New York Times because he thought the newspaper violated his copyright when it printed a picture of a German production’s stage set and costumes for Mozart’s Così fan tutte that resembled some of his caricatures. To support their contention that they had not committed copyright infringement, the Times ’s lawyers sent their correspondence with the German company, whose stage manager insisted that “they didn’t copy directly—merely followed your style.” Steinberg still wanted to sue and had to be persuaded once again by the ever-patient Alexander Lindey that litigation in this case would be both costly and futile.

Steinberg frequently created legal problems for himself by accepting every commission that came his way, regardless of whether one infringed upon another. A case in point concerned the Patterson Fabric Company, for which he had been designing for the past seven years. Other firms courted him throughout that time, and now, because the year was half over and he was still far short of the income he needed to support all those who depended on him, he accepted new assignments from other American companies and some foreign ones. Patterson Fabrics thought it deserved “slightly more consideration” than he was currently giving and sent an artfully couched letter hinting at its disapproval of his designing for other houses. The company warned that although it was true he would sell more by creating many designs, he would soon saturate the market and “decorators will tire of you.” It urged him to “consider this carefully.” He ignored the advice because he needed the money and continued to accept nearly everything he was offered.

For a variety of reasons, most of what Steinberg agreed to do was never realized; for example, the mural the Beverly Hilton Hotel had commissioned was canceled because of budget problems. He was quite excited when Harold Arlen, Truman Capote, and Arnold Saint Subber invited him to design the sets for the Broadway production of House of Flowers, and because he could not work on Broadway without union membership, he immediately completed the extensive paperwork required to join the Scenic Artists Union. It was a shock to everyone when his application was rejected. Nor was he mollified by an invitation to join the National Society of Mural Painters, but he accepted anyway and sent the $10 annual dues.

Despite his abrupt resignation from An American in Paris, Hollywood was still interested in Saul Steinberg. Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer asked permission to use his name in a movie called The Cobweb, which was set in a “clinic for nervous disorders.” The lead character was a patient who designed fabric patterns, and another character was to say of him, “I think [he’s] more like Steinberg.” Lindey sent the official refusal letter after the horrified Steinberg forbade MGM to use his name or anything else that might tie him to a mental hospital.

The volume of fan mail was equaled only by the requests for his work that poured in from commercial firms, most of which he accepted, with much of it coming due during his Stonington summer. Among the commissions, Remington Rand wanted cartoons for a promotional booklet for electric shavers; the Lawrence C. Cumbinner agency wanted ads for Smirnoff vodka; Jamian Advertising and Publicity wanted a two-page spread for ships designed to illustrate their Marco Polo line of fabrics. The Good Time Jazz record company of Los Angeles wanted designs for many of its record covers, and a St. Louis advertising agency wanted designs to illustrate a campaign slogan, “We teach copper new skills,” for the Lewin-Mathes copper tubing company. This one in particular led to a long, lucrative, and exceptionally creative association.

As Steinberg was striving to earn money, the summer of 1954 saw the true beginning of the requests that flooded in until the end of his life for donations of his work as well as his cash. Everyone from the Citizens Art Committee for the New Canaan, Conecticut, public schools to the satirical French newspaper Canard Enchaîné wanted him to donate drawings. The Boston Museum of Fine Arts asked specifically to “borrow” the baseball drawings, but the request carried the underlying hope that he would donate them. Roland Penrose began what became an annual plea for Steinberg to send a drawing to the ICA for its fund-raising. There were also requests from individuals who wanted him to draw something on a specific subject, such as the socialite Babe Paley, who asked for a Siamese cat she could give her husband, William S. Paley, the head of CBS, for Christmas. Hedda chafed because Saul spent so much time fulfilling these requests that he neglected his own work, but she never expressed her feelings to him: “He thought this country gave him a lot, and he could afford to give something back.” After a thoughtful pause she added, “He was afraid people would think he was cheap if he didn’t. He didn’t want the stigma that he was a cheap Jew.”

IT WAS HOT IN NEW YORK in August 1954, but Steinberg had to be there to finish all the work that was due before he left in September for Paris and Milan. Publication of The Passport was requiring his attention, and there were frequent meetings with his editor, Mike Bessie. Bessie had become one of Steinberg’s fast friends, and the friendship boded well for their publishing collaborations, because Steinberg was a nervous perfectionist and Bessie was adept at soothing him.

At the same time, an extraordinary amount of correspondence had accumulated, starting with his father’s American brothers and some of their offspring, whom he called “the Denver and Saint Paul Steinbergs.” Both contingents had contributed money and energy to bringing Saul to America and were now just as eager to help Lica and her family leave Romania, which was why so much postwar correspondence was generated. And as the uncles’ children grew up and Steinberg’s fame increased, the letters came most often from the cousins, who saw his work in magazines and wrote to praise it. His cousin Judith Steinberg Bassow in Denver became the most frequent correspondent because of her interest in his work and the genealogy of the Steinberg family, but it was his cousin Phil Steinberg in Arizona with whom he felt a special affinity and to whom he became increasingly close several years later.

There was even more correspondence connected to his European trip in late August. He made a brief stopover in London, followed by several weeks crammed with activity in Paris, before he went to Milan to work on the mural he had agreed to design and execute for Ernesto Rogers. The list of people he had to see and the things he needed to do before he could begin the work was staggering. Bessie wanted the names of people who could provide blurbs to promote The Passport; Steinberg offered Dorothy Norman, Igor Stravinsky, Jane Grant, Alexey Brodovitch, and Walker Evans, all of whom agreed. For the opening reception, he invited what would appear to an outsider to be a glittering list of celebrities but who were in actuality people with whom he had formed friendships that were both genuine and lasting. A contingent from The New Yorker included Shawn, Truax, Hellman, and Geraghty. Uta Hagen, Herbert Berghof, and Stella Adler represented his friends from the theater; Mary McCarthy, E. B. White, Ben Grauer, John Gunther, and Edmund Wilson represented literature; and from the worlds of art and design, Walker Evans, William Baziotes, Mark Rothko, Jose Luis Sert, Alexander Calder, Marcel Duchamp, and Alfred Barr. Everyone, it seemed, was invited, from Leo Lerman to Adlai Stevenson, and everyone accepted.

Steinberg’s list of people to see in Paris was even longer and contained the names of many he had met the year before through Aimé Maeght. From the literary world the names Steinberg put on the invitation list included Janet Flanner, Albert Camus, Sylvia Beach, Adrienne Monnier, Henri Michaux, André Malraux, Paul Painlevé, and Jacques Prévert. Noticeably absent were Jean-Paul Sartre and Simone de Beauvoir, whom he had never forgiven for snubbing Hedda in the bar at the Pont Royal. Baron Rothschild led a sizable contingent from the social world, and that resulted in a number of invitations that he accepted. Some of his best friends from the art world did not attend the opening but wanted to see him privately—Hélion, Giacometti, Cartier-Bresson, Dubuffet, Doisneau, and Miró—so he made appointments to see them separately. After he squeezed everyone in, he was ill and run-down and had to stay for an extra day in Paris because he could not get out of bed.

THE FLIGHT TO MILAN WAS BUMPY, and by the time he checked into the Hotel Duomo, he was “very sick,” not only with the upset stomach he was certain came from air sickness but also with a raging head cold and the flu. It was only August, but it was cold and rainy and felt like November. For the next several days he had to force himself to get out of bed and go to work in the rain while someone held a large umbrella over him. Rogers’s firm, BBPR, had been commissioned to create a labirinto dei ragazzi, or children’s labyrinth, for the tenth Milan Triennale. Steinberg’s drawings were on all the walls, and no matter where the viewer entered, there was a Steinbergian panorama to guide him to the center and into the two other wings, the entire structure resembling a kind of three-leaf clover.

He had created the designs on long sheets of scrolled paper before he left New York, then mailed them to Milan to be enlarged to the proper size for the walls. They were then transferred a second time, to a kind of paper that could be placed directly onto the freshly applied plaster so he could do the actual sgraffito, incising the designs through the paper directly onto the walls. He was prepared for the worst when he arrived, because everything from the weather to his health had been so dismal, but when he saw what the “three incredible boys” (two painters and a sculptor) had done, he was so pleased that he did something highly uncharacteristic: he insisted that the three men pose in front of the mural to have their photo taken, with him beaming at their center. He told Hedda that sgraffito was “a wonderful technique” that would solve all his problems for any future murals and he hoped there would soon be another. In the meantime, he planned to experiment on the walls at home, “in the basement perhaps.”

It rained every day, and he could legitimately have stayed in bed until he was well, but he was captivated by the mural’s progression and so he worked alongside his three assistants, improvising all the time. He flitted among them to make spur-of-the-moment additions, many of them easily recognizable Milanese landmarks. Some were whimsical, such as his rendering of the Castello Sforzesco, placed directly in front of where the castle could actually be seen if adults (and the children they held) raised their eyes to look over the wall. All the drawings inspired feelings of fun and laughter as viewers traipsed along the walls, and most of the reviews took note of the joy that people expressed. Steinberg’s labyrinth was so different from the formality of all the other exhibits that the New York Times critic declared that it stole the exhibition. All the other designs and structures were “serious, professional, and well-meaning,” but the only “humanity and humor” in the entire Triennale was found in Steinberg’s drawings. It was high praise indeed, especially welcome because it came in his old hometown, but it was difficult to bask in it for long.

On August 29 the partners in BBPR gave a party in their studio to celebrate the opening, which was for Steinberg a reunion of ghosts. No liquor was served, so there was nothing to make him feel (in one of his favorite slang expressions of the time) “snappy.” Most of the guests had been his professors and classmates at the Politecnico, and it was grating to be kissed on both cheeks by old teachers who hadn’t given a hoot about him as a student. Even worse were the snide, damn-with-faint-praise articles in magazines he called stupid about how successfully American he had become to command mille dolari al disegno (a thousand dollars per drawing). The hardest thing to deal with was the culture shock when he realized that he was so deeply imbued with American values that he could not accept the postwar Italian way of conducting business in the worlds of art and culture, the raccomandato of “I do something for you, you do something for me.” Whether it was truly far more blatant in Italy than in New York or Paris, or whether his entire Milanese experience was so disorienting that he needed to find a scapegoat for the depression that enveloped him, it was no longer something he could take as par for the course. It left him deeply unhappy to think that the country he had so warmly embraced and that had embraced him in return now considered him a foreigner. The only high spot came when Alberto Lattuada and Aldo Buzzi arrived to make a movie and he was given a walk-on part as a passerby in a scene they shot in the Galleria. Even this pleasure of being with old friends was double-edged: “It was ok but they felt they had other obligations and at times it was clumsy.”

WHEN HIS WORK WAS FINISHED, he told Hedda he wanted to go to Bergamo to have lunch with Aldo’s mother and then go directly to Venice for several days to decompress after all the work and socializing. He said he planned to see no one and have several days of the privacy that he had been without since leaving New York, but he did not tell her his real reason for going to Venice: that he needed to sort through the welter of emotions that came from seeing Ada again. For the past several years, besides regularly sending her money, he had managed to see her on most of his trips, and when he was in New York he telephoned regularly for long, secretive, and rambling conversations. However, once he resumed their liaison, he was so embarrassed that he kept it secret even from Aldo.

There had been three previous postwar encounters between them before this one, and all had ended badly. She felt the first went poorly because of “insincerity” on both their parts, the second because he cynically made fun of her extreme neediness, and the third because he told her he had to flee from her excessive passion and if she had any pride left at all, she would disappear from his life forever. Ada’s letters were a case study in self-contradiction. If she responded at first with histrionics, insisting that brain cancer would be preferable to the emotional torment and suffering he caused, which made her so ill she would soon die of whatever disease it caused, she would then swiftly become compliant and pacifying, with her next sentence, meant to be soothing, saying that all she wanted was to spend time with him, not necessarily in bed, just in his company; to be “maternal” rather than sexual. All she needed from him was “for the phone to ring,” but when he did call, he had to listen to a series of elaborate dodges that she invented, claiming they were necessary to keep the affair hidden from her husband.

While he was working on the mural, even on the days that he was sick, he managed to slip away to meet her secretly. She still traveled a lot, always being careful never to specify the reasons, and when she was in Milan, she lived once again with her husband in an apartment on the Viale Misurata, not far from where Steinberg was working. She arranged for them to meet halfway in between, in an apartment belonging to the girlfriend who had provided cover for them before the war. Ada was content with this arrangement, having accepted that Saul was married and so was she. She assumed that when he came to Milan they would resume their affair as if no years had intervened since he had been a student at the Politecnico, and when he left, each would return to their legal partner. This was easier for her than for him because she claimed never to have loved her husband, whereas despite his constant infidelity, he truly did love Hedda.

By the time he left for Bergamo and Venice, he was in an emotional turmoil because of everything that had happened during his time in Milan. Ada left him reeling; he had been affronted by the former colleagues who mocked his Americanness and by the two-faced behavior of his former professors, who now claimed they had known all along that he was a genius. Most troubling of all was his own shame about the duplicity of his relationship with the wife he professed to love above all others and the lover on whom he placed all the blame for luring him into bed each time he saw her. He could not help but contrast the two women.

When Hedda wrote letters, they were always on two levels. Hedda was a voracious reader, and she generally began with a philosophical interpretation of passages from books that she thought had relevance to their lives. Often she used them to launch into news of household happenings or of social occasions with their friends or events in the art world, because so many of their friends were artists. When Ada wrote, it was usually to tell him that he had left her in such a state of orgasmic ecstasy that she was having difficulty returning to married life with her dull husband. Her letters were blunt recapitulations of their time in bed, which almost always ended with how his departure left her ill and unable to work. She never asked directly but always implied that being unable to work meant that she sure could use some money. Ada was adept at blithely telling contradictory lies one after the other and getting Saul to accept them unquestioningly. First she told Saul that she was in such dire health from an undiagnosed illness that her husband, who “knows the cure for my ailment” (that is, Saul), actually took pity and guided her to the post office so she could mail a letter to him. In the next sentence she told Saul that mailing the letter immediately cured her, and as an aside told him to use her maiden name and a post office box number so her husband would not find out they were having an affair.

Saul hoped that several days alone in Venice would help him decide what to do about Ada, especially whether to end the affair permanently before it became a public embarrassment. He decided not to tell her that he had to return to Milan for a number of public events scheduled to conclude all the necessary dealings with the mural and let her think he was going directly to France and England and then home to New York. However, Milan was a small town, and it was not difficult for Ada to find out that he had been there. It made her furious even as it made her more determined than ever to stay in his good graces. In a series of letters, she first told him that she was working as a teacher but did not specify where, only joking that the work made her eyes so weak that she had to buy new glasses, which made her feel not only “old” but also “ridiculous [to be] still in love.” As soon as she told him she was a teacher, she changed her story in the next letter, saying that she had joined the theatrical company Senza Rete (Without a Net) and would be on tour in Padua, Florence, Naples, and Rome until the end of the year. After these illogical contradictions, she lapsed into fury, berating him for being his “usual pig” self, afraid to let anyone see him with her. She knew he had returned to Milan, not only because of the publicity surrounding the children’s labyrinth but also because the writers for the theater company knew of their relationship and took delight in teasing her about how they had been with him and she had not. She demanded to know if he was afraid of the gossip that might have reached Hedda if they were seen together—or was it something more serious, that he did not want to see her anymore? “I can’t help but tell you that you are”—and here she left a blank space before concluding that it was such “an ugly word” that she was unable to write it. Instead of ending the letter with her usual effusive phrases of love straight out of a romantic nineteenth-century Italian novel, she signed it with what was for her a cold snub, a simple “Ciao.” A postscript offered another contradiction, as she instructed him to write to her in care of yet another new post office box so her husband would not discover they were back in touch.

THE FEW DAYS STEINBERG SPENT IN Venice before he went back to Milan were disappointing, as he did not resolve his emotional confusion. The weather was disagreeable and the food not to his liking, and once his work was finished in Milan and all the celebrations were over, he could not return to New York without making the obligatory visit to his parents in Nice. It was, as usual, “horrible.” His father was slowing down, but his mother had deliberately lost weight and was in fighting trim to harass him more than ever. He planned to get through the visit by giving them money and behaving, “as usual, like Santa Claus.” This did not assuage Rosa, who spent her time with him listing all her friends who had died since his last visit and all the family disasters in Israel. His father couldn’t get a word in edgewise. The only time Rosa was happy during Saul’s visit was when she read and reread the first letter Lica’s son, Stéphane, wrote to her, saying that he was well and his baby sister, Daniela, “eats carrots.” Always before when Rosa talked about Lica and her family, her mood improved, and Saul had a brief respite from her dire accounts of gloom and doom. This time was different, as Rosa berated him for not telling her about things Lica had told him, which Lica had asked him not to reveal to their mother and then over time had inadvertently revealed herself.

Lica was understandably depressed by not being able to leave Romania, where her life was far from easy. Her husband had a series of undiagnosed illnesses and his job was in jeopardy; she herself had been ill and was worried about losing her job. Stéphane had had a serious case of scarlet fever, and now, with a second child, Lica was worried about basic issues of survival. She told one sad story after another of her own family’s misfortunes as well as those of their various relatives and former neighbors. They all begged her to ask her rich American brother for help, and she did. She was still angry over one particular incident that had taken place two years earlier, when she asked him to send medicines via American Jewish agencies to “the daughter of the cardboard maker on Strada Palas.” When they never arrived, she accused him of doing nothing: “If you could’ve helped her and you didn’t do it, then you committed a crime against her.” Lica told Saul she was still so bitter that it was difficult to return to thinking of him “with love and admiration.”

Lica’s charge was unjust, for he had sent both money and medicines to her and the others every time she asked. When Rosa learned of it, she changed tack and scolded Saul for trying to send money directly to Lica, since other efforts made through relief agencies had failed, and now her Communist bosses were threatening to fire her after they learned that she had rich relatives in America, which made her untrustworthy. As far as Rosa was concerned, it was all Saul’s fault. Rosa was crafty enough to know that her letters upset him so much that he seldom answered them, so when she wanted money or goods, she wrote directly to Hedda, often giving the names and addresses of all their relatives and friends in Israel with instructions about how much financial help to send to each. Hedda told Saul she was disgusted and stopped replying. Saul told her that the house in Nice was flooded with six years’ worth of letters from him and Lica that his parents insisted on reading and rereading aloud every time he visited. It was no wonder that he cut this visit as short as all the others, once again inventing urgent reasons that he had to go Paris, England, and then home.

The Passport, his “third, most overstuffed and diverse” collection of drawings, appeared in New York in October. He had indeed crammed all the drawings he wanted into the book, and every edition contained them all, including last-minute additions like the March 20 New Yorker cover. The book was another of his autobiographies, which he told through drawing rather than writing. There were false documents, diaries, and journals, and photographs real or invented, all doctored to make them as elusive as the documents. Several pages featured an artist drawing himself, with squiggles above his head or surrounding his torso. He used fingerprints to create human bodies and little birds with sticklike beaks and legs on graph paper. Cats tumbled freely about and crowds gathered to watch parades and festivals that featured flags, floats, and his iconic drum majorettes, whose legs ended in dangerous stiletto boots. There were couples in which he made either the man or the woman the dominant figure and cocktail parties where people talked past each other, always on the lookout for someone more interesting than the person they were with. He drew pages of riders on horseback, of cowboys and equestriennes. Musicians played before backgrounds of musical paper while dancing couples moved about on white space vacant of any other scenery. All the railway stations, bridges, and buildings that had fascinated him in England were there, as were French Métro stations and elegant Parisian buildings and monuments. Two shadowy men played billiards and shot pool; scenes of domestic life showed women dining with statues rather than real men; children in Victorian dress posed in front of houses straight out of Charles Addams’s cartoons. Several iconic drawings appeared here as well—the sign painter whose final k drops off the word Think; an artist who sits before a blank sheet of paper with only an ink bottle beside him. Another drawing features the objects that cluttered Steinberg’s real-life desk: an empty Medaglia d’Oro coffee can, a tin of Altoid mints, a bottle of India ink, a postage scale, and a packet of Philip Morris cigarettes. Two trees of life depict the lives of a man and woman who advance from infancy to adulthood and then decline into old age. Street scenes from Paris, Nice, Istanbul, Venice, and Los Angeles are interspersed among the individual drawings. Steinberg’s keen eye takes note of some important postwar changes in American life: a couple stands proudly in front of a Levittown house that is dwarfed by its garage and the gigantic car beside it. He reveals the expansion of supermarkets and strip malls and the architectonics of the new skyscrapers, particularly the ugliness of brutalism. Streets are torn up and shadowy blobs represent the human figures who here and there dot them.

He was satisfied with the American edition, but he wanted to make sure that the British edition being published by Hamish Hamilton was up to his rigorous standards. The book was being printed in Edinburgh, but Steinberg insisted on seeing the proofs before publication and was willing to take the time to go to a city he had not liked at all on an earlier visit. He traveled there by train in a sleeping compartment as antique as the publisher’s representative who went with him. The man wore “a striped suit and mellon [sic] hat,” and their compartment was made of “mahogany, brass, and ivory,” with a small compartment in the wall for the chamberpot. There was much fodder here for drawing, and he made note of it for future use. When he inspected the proofs, he did not make a single change; in fact, he thought the book looked better than the American edition.

On his return to London he visited Victor Brauner and his wife, Jacqueline, who were living in straitened circumstances. It was depressing to see a mouse calmly staring at them from behind a broom in the corner. Brauner was old and unwell, and his wife had just returned from the hospital following her second major operation. Steinberg’s sadness deepened when he returned to the hotel to find a letter from Hedda telling him that his uncle Harry had died and to break the news to his parents and send condolences to his uncle’s widow. With illness, death, and suffering all around, he was more than ready to go home, but once again there were problems with the airlines.

He could get to Paris but could not get a direct flight from there to New York. He did have to see Mrs. Jennie Bradley, so there was a legitimate reason to fly home from there. While he waited, he went to the movies (Pane, amore e …, Fantasia), read popular books (Françoise Sagan’s Bonjour Tristesse), and spent a lot of time walking to American Express to see if there was mail. Nothing he saw inspired him to draw, not even the “passersby loaded with children and suitcases” or the “tourists, sailors, dogs, prostitutes” who interfered with “the café workers making their rounds, and the street workers who drilled the asphalt directly in front of motorcycles, buses, ambulances.” All of this would have been transferred to notebooks and turned into drawings had he been in a better mood, but he was tired and wanted to go home.

He had even lost interest in writing to Hedda, which led to a flurry of telegrams to see whether something had happened to him. He was uncharacteristically sullen when he told her it didn’t matter if she didn’t write because her letters mostly consisted of news clippings or quotations and there was seldom anything personal. He had been alone far more on this trip than on most others, and he didn’t like the introspection that resulted. He realized that when he was the center of attention in social situations where he did all the talking, very little of what he said was “real.” Everything became formulaic because it was simplified chatter and therefore “seldom true.” He was full of self-pity and self-castigation for having let himself become a self-invented construct. His “Balkan fatalism” was overwhelming, and it was time to go home and sweep his stables clean.

CHAPTER 17

Дата добавления: 2015-10-30; просмотров: 177 | Нарушение авторских прав

| <== предыдущая страница | | | следующая страница ==> |

| THE DRAFTSMAN-LAUREATE OF MODERNISM | | | SOME SORT OF BREAKDOWN |