Читайте также:

|

As far as I could ever see, Saul never did anything to bring about his success. It just fell into his lap. All he ever did was draw, and the rest came by itself. Saul Steinberg and his friends, Leventer and Perlmutter, arrived in Milan in the fall of 1933 to begin their architecture studies at the Regio Politecnico. Three penurious students, they moved from student housing into one furnished room after another until they found something fairly decent and affordable at Viale Lombardia 21. The bathroom was a shared toilet at the end of a long hallway, but the room was on the top floor and filled with light from a window that opened onto a tiny balcony just big enough to hold a potted plant, which they jokingly called a “terrazzo.” They were thrilled to have the room, although they were not so thrilled with its only decoration, the testa di cavallo, an embalmed horse’s head that hung directly above Leventer’s bed. The roommates agreed that it ranked somewhere between frightening and disgusting, but they were too cowed to ask the landlord to take it down.

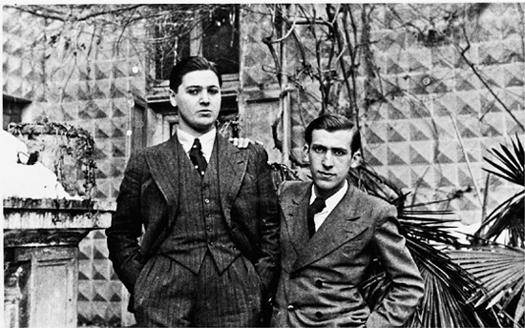

Steinberg in Milan with an unidentified classmate at the Politecnico. (illustration credit 5.1)

Steinberg in Milan with an unidentified classmate at the Politecnico. (illustration credit 5.1)

Saul Steinberg’s official registration in the school of architecture was dated November 17, 1933, and on December 16 he was officially enrolled as a first-year student in the Regio Politecnico, ID number 33–34/81. His actual entry to the school had come in September with the convocation that signaled the start of the semester, on the day before classes began. After the ceremony, the “skinny little fellow with the big nose and heavy glasses” was noticed by another student who was also loitering in front of the building on the Piazza Leonardo da Vinci. This was Aldo Buzzi, a native of nearby Bergamo, who had enrolled in the Politecnico after a lackluster year in a music conservatory because “the architecture department was the place to go if you were not sure about what you wanted to do with yourself.” Steinberg initially attracted Buzzi’s attention because “there were so few foreigners in the school and everything about this one seemed different and out of place.” Something told Buzzi that this other student was a kindred spirit, since they were both behaving as if they had nothing else to do and nowhere to go while everyone else had rushed out of the convocation intent on last-minute preparations—first for lunch, then for classes.

Steinberg and Buzzi fell into step and began to talk, and as one subject led to another, they found themselves deep into a philosophical discussion of what would happen if an artist drew a single line and allowed it to evolve into a drawing. When Steinberg became so excited by the subject that his Italian faltered, they switched to French, a language they both knew well enough for a spirited conversation. This became the first of many during the next seventy years and the basis for a rich correspondence when they were not together. Despite the ease with which their friendship began, Aldo was aware from the start that Saul was a very private person who kept most of what he thought or did to himself. At first Aldo thought of him as a poseur who was merely trying to keep his insecurities from being seen by others, but as time went on, he realized that this was Saul’s true personality, and he learned to respect it.

Becoming Aldo’s friend was exceedingly helpful to Saul as he sought to blend into a life far different from what he had known in Bucharest. The Poli, as the students called it, was both bohemian and sophisticated, and by studying everything Aldo did or said, what he wore, how he interacted with the other students, and even how he smoked his cigarettes, Saul was able to avoid most of the gaffes a foreigner would unwittingly make. Aldo’s self-confident descriptions of his native Bergamo seemed the epitome of refinement to the “nervous Romanian boy in the ill-fitting, mismatched jacket and trousers.” Saul was impressed when Aldo told him that his second cousin, Tommaso Buzzi, was on the Politecnico faculty and would be their instructor for disegno dal vero (drawing from life); he was even more impressed when he learned of Tommaso Buzzi’s distinguished reputation as one of Italy’s foremost designers.

Aldo was the son of a widowed mother, and like Saul, he had to count every penny. He was a font of information about bargains, the most important being where to find the most food for the least money. At the top of the list was the local latteria, a “milk shop” that went by the improbable name of Bar del Grillo, famous among poor students for serving heaping plates of rice lavished with butter. Years later Saul still savored the memory of “gigantic portions of rigatoni al sugo with sage twigs and all the bread you could eat, followed by goulash or stew drowned in red sauce, which you mopped up with the endless bread.” But he could not afford even that during his first year, 1933–34, when the Romanian leu was weak against the Italian lira. He could afford to eat once a day, and he had that meal at noon in the student restaurant, where he could take as much pasta or risotto as he could load onto his plate, always topping it with a fried egg if eggs were on the menu. In the evenings he ate surreptitiously in his room, having smuggled out at lunchtime a Milanese panini, which he covered with butter and gorgonzola or a smattering of peach jam—for as long as the supply he brought from home lasted. He drank water and went to bed hungry, consoling himself with food fantasies as he recalled his mother’s enormous meals of “terrible Jewish-Romanian cuisine.”

By his second year in Milan, he had overcome his shame and shyness to join his classmates regularly at the Bar del Grillo, where students could nurse a single coffee for hours and buy cigarettes and postage stamps. Shortly after, when the shabby hangout became the first commission of Ernesto Rogers and his newly founded architectural firm, BBPR, what had been a mismatched collection of cheap wooden tables and chairs was turned into a sleek example of modern Italian design, all black lacquer, shiny chrome, and stainless steel. However, despite its gleaming splendor, the bar’s location just down the piazza from the Politecnico guaranteed that it would remain the same old neighborhood fixture it had been during its incarnation as a latteria. It was Saul’s local throughout the 1930s, and for a few years it became his address, Via Pascoli 64, when he rented a room above the bar; for the rest of his life, it became an iconic talisman for triggering happy memories. Even after it was long gone, he praised the Bar del Grillo as “the best kind of propaganda for a modern architecture.”

He never forgot the four Cavazza sisters, who had inherited the bar from their father, an old man who dozed away his days in a chair near the sunny front window. His was “the face of a Roman senator which had been passed on to his daughters with disastrous results.” Angela, “the oldest and most ferocious,” presided over the cash register. Saul was amused by her name, “given her face, a real Leonardoesque caricature of a warrior in the act of killing somebody.” The next daughter, Natalina, was the waitress, “a real spinster, less ferocious, even a bit more maternal.” She served the food cooked by Maria, “enormously fat, of whom one saw only her bust” as she passed the dishes through a little window that separated the kitchen from the restaurant proper. Saul noticed that the fourth sister, Carla, was “not bad looking,” but he never made a pass at her because she had a fiancé “and would vanish every now and then for a day or so.”

Student gossip held that the Bar del Grillo got its name from the trigger on a pistol, or grilletto, which the students insisted was also the most common slang word for the clitoris. It might have been, in some obscure dialect other than Milanese, but Saul knew that the name was bestowed by the original proprietor, an Italian who came home from America and garbled the English words bar and grill. To him, it was “the most perfect name for a restaurant with dancing and rooms for rent by the hour,” and he quickly became a fixture among the students who gathered there. Having such a comfortable hangout was one of the reasons that, after his first poverty-stricken year, he never ventured out to see much of the city that lay beyond the bar, but the chief reason he stayed there was because he had so little money: after he paid for the bare necessities of survival, there was not much left for public transport and entertainment.

Milan was cosmopolitan in every way, a “laboratory for modernity,” internationally respected for art and architecture, graphic design, industrial development, fashion, and every form of culture from opera to literature. Although he lived in the city’s intellectual epicenter for more than eight years, Steinberg always insisted that his “autobiography” of that time was more of an “autogeography.” His entire world was bounded by the few streets located midway between the Metro stops of Piola and Lambrate and consisted only of “a particular neighborhood,” the working-class district surrounding the academic institutions that made up the Città degli Studi. His world became even smaller when Ciucu Perlmutter moved elsewhere and he and Bruno Leventer were left alone to settle in under the dreadful testa di cavallo. Living so close to the Poli, Saul needed only to make a short walk for morning coffee at the Bar del Grillo before heading up the piazza to classes. Then it was back to the Grillo to hang out.

Saul insisted that the strongest memory of his early years in Milan was of “solitude,” that he was never at home and always out, unable to make himself study, concentrate, or read. He “marched around like a soldier for hour after hour,” returning to his room only when he was “exhausted, falling asleep hungry but sufficiently happy.” When he walked the streets, it was in a daze as he stopped to read the menus and stare at the abundance of foods displayed in grocery windows. He looked with yearning at antipastos, pastas, roasts, and sweets, until he became so faint that he had to cross the street to get away from the sight and also from the reflected images of the girls who passed by on the sidewalk behind him. When he turned to look at them directly, their legs in sharp heels left him so dizzy with longing that his food fantasies had to compete with sexual fantasies in which he imagined himself taking part in all things witty, from conversations to courtships. If asked what he saw on his peregrinations, he could only describe the “abundance” of women and the “luxury to observe them in their infinite variety.” Food and sex were unreal dreams, out of touch and reach behind thick glass windows but nevertheless contributing to the artistic vision he was formulating: the plate-glass window was a barrier, but even so, it represented two important and useful qualities: transparency (the food) and reflection (the girls), both of which became the “symbol of reality becoming my art, my condition, my life.”

As an architecture student, Saul was aware of the new buildings that were springing up all over the city, but he never commented on them. Nor did he remember visiting the art museums and monuments that international visitors flocked to all year long, and he never mentioned politics, although Milan was a hotbed of Fascist intrigue from the beginning of Mussolini’s reign in 1922. His experiences in Romania had taught him how expedient it was for foreigners, particularly Jews, not to call attention to themselves. Having witnessed at first hand political persecution in Bucharest, he knew the wisest behavior in Milan was to fade into the background and become “the first-class noticer” that he was from those years onward.

However, Steinberg’s contention that he was always solitary and alone during his first two years in Milan (and even after) does not ring entirely true. His room became an informal gathering place for other students, and there were frequent parties. Every morning that the weather permitted, he went out onto what Leventer ironically dubbed “the terrace of our villa, in the shade of the dwarf palms,” where he would draw for hours. As soon as he met Aldo Buzzi he became part of a group of fellow students, mostly Italian and most of whom became lifelong friends as they went on to establish brilliant and distinguished careers. Among them were two who became luminaries in the Italian film industry, Alberto Lattuada, the writer-director who was later Aldo Buzzi’s brother-in-law; and the famed director Luigi Comencini. Sandro Angelini became a respected architect in Bergamo, and Erberto Carboni was already making a name for himself while still a student when he contributed to the internationally acclaimed avant-garde graphic design firm Studio Boggeri. Steinberg saw these friends every day in the classroom and the hallways, and the ones as poor as he and Buzzi often joined them for meals at the Grillo, while the ones who had a bit more money often stood drinks at the bar. Every day he had conversation and conviviality whenever he wanted it and companionship for anything social he chose to do. If and when he was alone, it was because he chose to be.

Saul had two major preoccupations during his early years in Milan, drawing and girls, and he indulged in both every day, most of the time managing to sketch and ogle in concert. Aldo joked that the notebooks he carried everywhere seemed to be “attached directly to his hand and pen,” but even though Saul insisted that the only thing he took notice of was “the luxury of women,” his notebooks attest that he saw much more. From his youth in Bucharest, when he first attempted to paint with oils on canvas, the smell of turpentine made him ill, so he concluded that he was probably allergic to it and tried never to use it. Instead of joining classmates who copied the paintings in museums, he chose to draw the life of the streets, rendering everything he saw with his characteristic firm black line and giving everything a touch of the whimsical and imaginative that was uniquely his own. He drew street scenes and buildings, especially churches such as the lofty San Lorenzo, and the glass-domed interior of the Galleria Victor Emmanuel II with its Café Biffi, which, as soon as he earned enough money to afford it, became one of his favorite destinations.

As for women, whenever he wanted to do more than look at them, he had several options, and he exercised them all. The skinny Romanian boy in the ill-fitting clothes very quickly became proficient in the Italian language and particularly the Milanese dialect, and in the process he discovered that women found his easy manner attractive. If he wanted to talk, plenty of young girls went to the Bar del Grillo to flirt with students, who could be counted on to buy them drinks, after which the girls might occasionally be persuaded to go upstairs to one of the rooms that could be rented by the hour. There were also nearby brothels on unobtrusive side streets, known to students and tolerated by neighbors, just so long as everyone was quiet and discreet. Later in life, when Saul joked that a friend’s red velvet furniture looked like something out of a Milanese brothel and she asked how he would know about such things, he only laughed and shrugged. His sole problem with women in those years was one of money, and sometimes, when he had to choose between entertaining a woman and buying a meal, he chose to go hungry—if no friend was around to float a small loan.

ALTHOUGH STEINBERG INSISTED THAT HIS “chief interest…was in girls, and he was hoping “to find [himself ] through love,” he had not gone to Milan to pursue women but to become an architect. As soon as his studies began, he became as sardonic about his profession as he was about his personal life. He thought the curriculum at the Poli was “marvelous training for anything but architecture” and joked that it was so “frightening” to think that one of his drawings might eventually become a building that he always took care to draw “reasoned lines.”

In the years that Steinberg was a student, the educational philosophy of the Politecnico lay somewhere between “cribbed Bauhaus” and “the influence of Cubism,” but the one certainty about the curriculum was that it was “comfortable” rather than demanding. Students often postponed final exams until long after they completed the courses—in some cases for years—and that is what Steinberg did. This casual attitude gave him all the freedom he needed to keep on with the style he had adopted when young, of “continuing and perfecting childhood drawing—without the interruption of academic training.” In later years he insisted that the Poli had exerted little, if any, influence on his mature drawing. What remained strong from these years were the memories of “places that don’t belong to geography but to time.”

In the first year of classes, the Politecnico students took courses that were divided almost equally between the rigidity of mathematics and science and the fluidity of art and the humanities. Analytical mathematics and advanced geometry were balanced by the history of art and architecture. Steinberg took two language courses as electives: German (then the language of science and necessary to understand technical publications) and English (the lingua franca for general international discourse). Students were required to study elements of construction, mineralogy, applied geology, and elementary architectural composition and drawing, but he also studied disegno dal vero, or drawing from life. The life-drawing courses were held at the Poli, but the student body was enlarged by groups from other area schools, such as the prominent Accademia di Brera, where painting and art history were the primary subjects. It made for an interesting mix of styles and opinions, and provided broader cultural insight into contemporary Italian art.

In dal vero, Tomasso Buzzi taught students how to see everything with a new and discerning vision, from human models to inanimate objects and still life assemblages. He would point to a view or an object and tell the students to draw it quickly, which brought a “revelation” to Saul, who told Aldo that until he took this course, he had only drawn from “fantasy” or “imagination.” Now he was finding both “surprise” and “passion” in everything he saw and drew, because of his teacher’s unorthodox way of exploring and explaining the world around him. The work he did in Tomasso Buzzi’s class had a special meaning for Steinberg; throughout his life he always threw away drawings that displeased him, “but rarely drawings dal vero. ”

Tomasso Buzzi was not only Aldo’s cousin but also the friend and collaborator of Giò Ponti, another of Steinberg’s professors, and he was the first of several (Ponti was later among them) who told Steinberg that he had the makings of an artist as well as of an architect—heady praise for a first-year student. Toward the end of the course, Tomasso Buzzi shifted the course content away from what the Brera students called “pure art” and toward what he called “documentary” drawings. In the days of the T-square and slide rule, these included the architectural segments and components of buildings that students drew by hand before computer programs rendered such drawings obsolete. Steinberg’s versions of some of the “documentary” drawings were of interiors as grand as the Galleria, simple layouts of living rooms and bedrooms, and building facades and decorative columns. Here again, in pencil and ink lines of varying blackness and width, he subjected such concepts as distance and perspective to his particular vision. Straight walls appear slanted and off-kilter, furnishings are distorted, and hallways and corridors are either foreshortened or made to loom unnaturally large. He tried to explain what he did by saying that his work always said “something about something else” and that his intention was always to show “something more than what the eye sees.”

Interestingly, the nuts-and-bolts courses that formed the greater part of the curriculum offered other ways for him to use what he saw to represent and describe something else entirely. Arturo Danusso, already respected for an important series of published papers on the use of reinforced concrete slabs, taught a structural engineering course that was pure mathematics combined with solid geometry. Ambrogio Annoni, a distinguished architect who specialized in architectural restoration, taught “drawing from nature” in a course titled “organisms and forms of architecture.” The student body for this course was a combined group of architecture students from the Poli and art historians and restoration specialists from the Brera, and the mix made for some exciting discussions. The eclectic Piero Portaluppi, considered one of the main protagonists of architectural culture in Milan, used his courses to provide students with practical work experience for the many important commissions he executed between the 1920s and the 1950s. Giò Ponti, in an interior design course, taught Steinberg to see every object in a room with the same sense of astonishment that Tomasso Buzzi inspired, and to commit it to paper with the refreshing originality that became a hallmark of Steinberg’s vision.

Despite Steinberg’s insistence that the Poli had little influence on the development of his style, it is not too far-fetched to find traces of what he learned in these courses in the later drawings that puzzled and delighted legions of admirers. The classes sparked his initial knowledge of and lifelong interest in the history of art and architecture, but just by being in Milan he gained the confidence to be a snob about art and architecture, to know what was good and dismiss what was not.

His courses fed his imagination but did not become illuminating experiences until he began to take the required field trips that complemented classroom instruction. Students went to several factories throughout the Piedmont region that specialized in manufacturing various materials used in construction, among them a cement factory in Ferrara where they saw the practical application of Danusso’s research. One of the best trips was Steinberg’s first to Rome, where the students were taken to monuments, ruins, and buildings old and new, then left free to let their imaginations carry them on waves of creativity. Steinberg became “a very, very precise observer of the world, a profound and precise draftsman” as he drew the required “documentary” drawings. His line became firmer, more assured, and to his surprise his personal sketchbooks filled far faster than those that were required. His creativity overwhelmed his course work, and because he was not concentrating on class preparation but was branching out into other, more artistic areas, he was not prepared for most of his examinations and delayed them.

He thought he had plenty of time to deal with bureaucracy whenever he was ready to confront it, even though the years from 1933 to 1936 passed with astonishing speed. He worked hard during term time but was still relieved when he went home to Bucharest every summer to satisfy his parents’ questions with vague replies that he was making progress toward his degree and everything was proceeding smoothly and on schedule. He usually traveled by ships that sailed from Genoa or Venice, sometimes up the Danube, other times via the Black Sea. Occasionally he wended his way to Vinkovich in Yugoslavia, where he transferred to the Orient Express, which came from Istanbul. He didn’t work to earn money during his vacations, so when he returned to Milan, the over-solicitous Rosa usually stuffed his suitcase full of salami, halva, peach preserves, and cakes. His friends were happy to share the “pink, green, and blue box of sugary treats” that was usually piled on top of what Saul dismissed as merely “some drawings.” He filled sketchbook after sketchbook as a way of coping with his family and a way of life that had become foreign and distasteful. He saw himself becoming more Italian than Romanian, and just as he postponed his exams, it was easier to evade thoughts of having to return to Bucharest.

ONE OF THE THINGS SAUL CHAFED at during his early years in Milan was the constant lack of money, a problem that was partially solved one day at the end of 1936 when a brittle, fast-talking woman “just sort of appeared” in the Bar del Grillo, gave a hard, appraising look at all the men, and took a seat by herself at the bar. Ada Cassola had blue eyes and dark blond hair and wore her skirts a fair bit shorter than modesty required. Aldo remembered her as “tall, thin, angular, and not really a beauty; many would say she was not even pretty, but there was something striking about her, and her personality fused with what Saul was looking for in a woman.” Like Saul, Ada was an exceedingly private person. She allowed the habitués at the Grillo to believe that she had come to Milan from a small town somewhere to the west or south, perhaps in Liguria, but she had no trace of an accent and did not speak a dialect native to that region or any other. She spoke Italian with a cultivated accent that sounded both practiced and acquired, and when she did lapse into the Milanese dialect, she was able to speak it fluently. She evaded Saul’s questions, especially about her age, but he eventually discovered that she had been born in 1908, which made her six years older than he. She told him she had no family and stuck to the story that she had come alone from an unnamed small town to seek her fortune in the big city. She never spoke of how much education she had or whether she was prepared for anything other than menial work. In the beginning, Ada helped out as a waitress at the Grillo and as a cleaning woman for the rooms above, but she had bigger dreams and did not do such work for long.

Ada Cassola Ongari, Steinberg’s “beloved Adina.” (illustration credit 5.2)

Ada Cassola Ongari, Steinberg’s “beloved Adina.” (illustration credit 5.2)

Her mysterious comings and goings provided irresistible gossip for all the regulars at the bar, but neither Saul nor Aldo could get a straight answer about how she suddenly seemed to have all the money she needed without ever appearing to do any work. Aldo thought she might be a fence for stolen goods or a smuggler. Both possibilities gained credence when she gave Saul a cigarette case and wristwatch and shortly afterward was arrested for smuggling contraband cigarettes. A bribe to a local official got her off that time, but she did have to lie low for a while, and Saul and Aldo had to pitch in to help cover her expenses. Nothing daunted Ada: she was fearless, always up for a dare, and after World War II began, she smuggled contraband right under the noses of the Nazis.

Ada remained a major presence in both men’s lives until her death at age eighty-nine in 1997. For Aldo and later for his wife, Bianca Lattuada, she was a “mystery to the very end: never once did she speak of her family or her origins; never once did she reveal anything personal about herself.” Saul was utterly besotted with Ada; she was the first woman to captivate him totally. He begged her repeatedly to marry him, but time after time she stalled, giving one reason or another. She was so elusive that when he was not drawing or going to classes, he was almost always trying to track her down so that he could be with her. However, fidelity was never his strong suit, and there were other female diversions at the Grillo. The regulars did not hesitate to let Ada know that Saul had gone off with “the little red-haired girl,” and she was furious when she went to mail a package to him and the postal clerk smirked, saying that she “knew” him. “Naturally you will say you don’t know her [but] I know you have a soft spot for fat blondes and unfortunately I am not one,” Ada wrote to him. She didn’t like it when he went off with other women, but as she had her own reasons for secrecy, she seldom complained; however, in this case she was so angry she said she could not write to him again until she “cooled down.”

Ada and Saul before the war. (illustration credit 5.3)

Ada and Saul before the war. (illustration credit 5.3)

Ada may have been a fearless and independent woman, but in Mussolini’s Italy she had to practice discretion. Saul did eventually spend nights in her room, although for a long time he had to pretend to be visiting her at various girlfriends’ apartments, from which the girlfriends would then conveniently absent themselves. For the most part, Ada quietly arranged their assignations for somewhere other than Milan. She liked the tourist towns in Liguria, and Varazze was a favorite destination. She would stop there on her way back to Milan after one of her mysterious absences—usually to Genoa—and send telegrams and letters asking Saul to meet her in a certain boardinghouse where she had reserved a room in his name. She cautioned him not to tell anyone where he was going and to avoid being seen by anyone who might recognize him when he walked from the train station. What she didn’t tell him, in these letters or in person, was the primary reason for her discretion: that she had a fiancé—if not actually a husband—Vincenzo Ongari, who lived in a nearby town in Liguria that she regularly visited.

Дата добавления: 2015-10-30; просмотров: 142 | Нарушение авторских прав

| <== предыдущая страница | | | следующая страница ==> |

| A SECURE TRADE | | | THE PLACE TO GO 2 страница |