Oral Cavity and Teeth

The oral cavity consists of the lips, cheeks, tongue, hard and soft palates, and teeth.

The lips provide the anterior protection of the oral cavity. They help maintain teeth in their position, are important in speech, serve as a seal to prevent food and saliva from escaping and prevent foods that are too hot or too cold from entering the mouth.

The cheeks, the side walls of the mouth, like the lips, hold the position of the teeth and aid the chewing process by holding food against the teeth.

The tongue is a skeletal muscle with a specialized epithelial covering that contains the taste buds. It serves an important function in chewing, swallowing, and speech production.

The hard palate is the anterior portion of the roof of the mouth. It is a hard, dense tissue, which is still very sensitive and aids to protect the oral cavity from hot or very coarse food.

The soft palate is the posterior portion of the roof of the mouth. It functions to close off the nasopharynx during swallowing.

The teeth. The primary function of the maxillary and mandibular teeth is to grind and tear food. Their secondary function is to aid in swallowing and speech. Two sets of teeth develop during the lifetime. The first set is milk, or deciduous teeth, 20 in number. These usually develop shortly after the seventh month and are lost during childhood, when the second set of teeth, or permanent ones, appears. There are 32 permanent teeth, 16 in each jawbone.

The shapes of animal teeth give clues to the type of food they eat. Meat eaters have sharp, pointed teeth to pierce and tear. Plant eaters have broad, flat teeth to crush and grind. Humans are not exception. As a species, we eat both meats and plants, so we have different types of teeth to handle both types of food.

Incisors. The four front teeth in both upper and lower jaws (a total of eight) are incisors. The pair of teeth at the center of your mouth, top and bottom, are called the central incisors. The teeth on each side of the central incisors are the lateral incisors. All the incisors are broad, flat teeth with a narrow edge good for cutting or snipping off pieces of food. They have a single root.

Canines. On both sides of jawbone there are four canines (two in each jaw). Sometimes called eyeteeth or cuspids, canines are the longest and most stable teeth in the mouth. They are thick and come to a single sharp point, ideal for ripping and tearing at foods that might be tough, such as meat, and for piercing and holding. They have a long single root.

Premolars. Next to each canine there are two premolars (a total of eight). Also called bicuspids, premolars are a cross between canines and molars. They have sharp points for piercing and ripping, but they also have a broader surface for chewing and grinding. On the upper jaw, the first premolars (directly next to the canines) have two roots, and the second premolars have one root. On the lower jaw, all premolars have one root.

Molars. The last three teeth on both sides of your mouth, upper and lower, are the molars (a total of twelve). They are numbered first, second, or third molars depending on their location. The first molars also called six-year molars are those closest to the front of the mouth, directly next to the second premolars. The third molars, also called the wisdom teeth, are the last teeth, farthest back in the mouth on all sides. In between there are the second molars also called twelve-year molars. Molars are large teeth with broad surfaces designed for crushing, grinding and chewing food. On the upper jaw, the molars have three well-separated roots; on the lower jaw, the molars have two roots.

Dental Tissues

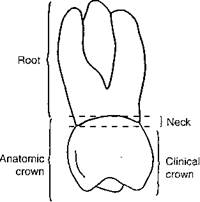

A tooth, in general, is made up of three anatomic structures: the crown, neck, and root.

|

Crown. The crown of the tooth is referred to as the coronal portion of the tooth. The portion of the crown that can be seen when examining a normal healthy mouth is called the clinical crown. It is a supragingival portion of the crown because it is above the gingival margin. The anatomic crown refers to the whole crown. Because the neck of the tooth is normally covered with free gingival, only the clinical crown can be seen. However, the crown of a tooth extends below the gingival margin or subgingivally, proximately 1.5 to 2 mm.

Neck. The neck of the tooth is that part of the tooth where the enamel of the crown meets the cementum covering the root portion of the tooth. This area is referred to as the cervical line or cementoenamel junction.

Root. The root of the tooth is that portion of the tooth that lies within the alveolar bone and helps to secure the tooth in position. The root makes up about two-thirds of the tooth. Teeth have varying numbers of roots. The tip of the root is called an apex.

In addition to the three anatomical structures – crown, neck, and root – the tooth is composed of specific hard and soft tooth tissues and supporting structures.

The hard tooth tissues consist of enamel and dentin. The soft tissue refers to the pulp. Cementum may be considered one of the hard tooth tissues or a supportive structure.

Enamel

Enamel is the translucent white substance, which covers the anatomic crown of the tooth. The translucency depends on the thickness of the enamel, and the white shading varies from a light yellow to a gray color. The enamel is that part of the tooth exposed to the oral cavity. Although enamel is the hardest substance in the human body and can withstand the biting and chewing forces of mastication, it is also brittle and subject to decay. The problem is that enamel cannot regenerate itself and therefore must be artificially replaced or restored if damaged.

Enamel is thickest on the working surfaces of the crown and thinnest around the neck of the tooth. Enamel is formed by ameloblasts and composed primarily of the minerals: calcium and phosphorus. Enamel is not structurally solid; it is made up of enamel rods or prisms that are encased in rod sheaths and bonded together by an interred substance. These rods are aligned parallel and extend in a perpendicular line along the dento-enamel junction.

Dentin

Dentin is the yellowish portion of tooth that makes up the main body. Dentin is covered by the enamel on the coronal portion and by the cementum on the root portion. The dentin contains the pulp chamber or cavity. It is harder than cementum but not as hard as enamel.

Dentin is formed by odontoblasts that continue to exist in the dentin next to the pulp chamber. The dentin developed during tooth formation is called primary dentin. Unlike enamel, dentin is a living tissue that reforms itself regularly and is able to repair itself in response to trauma or irritants. This reformed dentin is called secondary dentin.

Dentine is a porous tissue that contains many tiny canals called dentinal tubules. These tubules evolve from the surface of the dentin to the pulpal chamber. They are filled with sensitive, living tissue called dentinal fibers. These fibers contain odontoblasts that stimulate secondary dentin formation. Because of the sensitivity of the dentinal fibers and their active part in secondary dentin formation, the dentinal tubules must be sealed or covered during restorative procedures.

Pulp

Each tooth has a pulp chamber that is located in the coronal portion of the crown and pulp canals or root canals located in the root portion of the tooth. The pulp chamber has pulp horns that correspond to the cusps of each tooth. Dental pulp is the sensory soft tissue of the tooth located within the chamber and canals. It extends through an opening, the apical foramen, in the apex of the tooth root to connect with the nerve, blood, and lymphatic systems. Pulp consists of arteries and veins, nerve and lymphatic vessels, and connective tissues that nourish and protect the tooth. The nerves, for instance, produce a physiologic reaction by responding to pain, thus aiding in stimulating blood flow, odontoblasts, and fibroblasts. This process aids in the production of the secondary dentin, which help to protect the tooth from injury. When extensive trauma occurs, the pulp may become devital or dead.

The supporting tooth structures include the gingivae, cementum, periodontal ligament, and alveolar bone.

Gingiva

The gingiva is soft oral tissue that covers the alveolar bone and attaches to the teeth. It blends into the soft flexible oral mucosa that lines the cheeks, lips, vestibule (the space between the alveolar ridge and the lips or cheeks), soft palate, floor of the mouth, and undersurface of the tongue.

Cementum

Cementum is the thin layer of mineralized bonelike substance that covers the root portion of the tooth. Cementum is softer than enamel and dentin. Cementum is thinner in the cervical or cemento-enamel junction area of the tooth, where it may barely overlap the enamel. However, cementum is slightly thicker on the apex of the root. The purpose of the cementum is to provide an attachment for the periodontal fibers or ligaments that hold the tooth firmly in the tooth socket or alveolus. There are cellular and acellular, cementum-forming cells called cementoblasts. Cellular cementoblasts are located on the apex of the root, continuously reforming and reinforcing tooth attachment throughout a person’s lifetime. This reformation is often stimulated in response to trauma or the need to reinforce the periodontal ligaments.

Periodontal Ligaments

Periodontal ligaments are fibers embedded in the cementum. These fibers aid in attaching the tooth to the alveolus and holding it in proper position; they also cushion the tooth in response to trauma or normal forces of mastication. The predominate types of periodontal fibers are the apical, interradicular, transseptal, oblique, horizontal ones, and alveolar crest.

Alveolar Bone

The teeth are also supported by alveolar bone. Each tooth is positioned in a tooth socket or alveolus. The alveolus is lined with compact bone or plate, called the lamina dura, which can be seen on a radiograph as a light line encircling each tooth root. The periodontal fibers that are attached to the cementum also attach to this lamina dura and provide support for the tooth.

Bone is formed by osteoblasts and absorbed by osteoclasts. This process is particularly important in orthodontic treatment. Teeth are moved in a particular direction as pressure is applied to the tooth and against the bone. This causes the bone to absorb but also reform and fill in the space as the tooth moves.

Дата добавления: 2015-10-23; просмотров: 133 | Нарушение авторских прав

| <== предыдущая страница | | | следующая страница ==> |

| Credit rating & Rating agencies | | | MODEL FOR CLASSIFICATION OF APPROACHES |