SEMINAR 7. People of the USA (ethnic and religious diversity)

1.Short history of settlement of North American continent before 1600s

-Native Americans (indigenous people of North America)

2.Short History of the European Settlement of North America since 1600s

-waves of migration, laws, minorities

-patterns of settlement, diversity

-religion

3.Brief facts about the ethnic composition of the USA (2010 census results)

REFERENCES

1.Carmen D., Khrypun V.S. USA: A collection of readings. - Kirovohrad: KDPU, 2004. -

P.6-8, 67-80, 145-147.

2.Stevenson D. American life and institutions. - Stuttgart: Ernst Klett Verlag, 1996. - P. 14-32 (We the people).

TASKS

Take the map of the USA and try to find the original and present locations for the tribes mentioned in the text (optional).

2.Complete the timeline of settling of and immigration to the USA (a must). Use American Life and Institutions by D.Stevenson or this text for this task.

| Year/s | The country people came from, the reason |

| 20,000 years ago | Asian wanderers following animal herds |

| Icelandic Vikings under Leif Ericsson, exploration | |

| 1845-1849 | Ireland, potato famine |

| 1860-1890 | |

| 1881-1906 | |

| 1900-1920 | |

| 1948-1960 | |

| 1960-1970 | |

| 1975-1980 | |

| 1980-2000 | |

| 2000- |

GUIDING QUESTIONS

1. How did the Indians got their name?

2. Name the marks of the Indian cultural heritage in the U.S.

3.What was the traditional way of life of the Indians? What did and do they think about land and nature in general?

4.Give the history of Native Americans in the USA.

5.What is the situation with Native Americans nowadays?

6.When did the Native Americans become citizens of the USA?

7.What event is called the Trail of Tears?

8.Give the history of immigration to the USA, name the reasons of different people to emigrate to the USA.

9.What immigration laws were passed by the US government?

10.What is Ellis Island?

11.Explain the impact of immigration on American society.

12.What is the attitude of Americans to immigrants?

13.What is the biggest minority of immigrants in the USA today?

14.Discuss possible consequences of recent changes in the patterns of immigration.

15.Explain how immigration has contributed to the multiculturalism of American society.

16.Who is an Average American? Can we define him/her?

17. What is WASP?

18. Explain the meaning of metaphors “melting pot”, “pizza”, “salad bowl”. To which of the before mentioned is the metaphor “tapestry” closer?

19.What is the size of the territory and the population of the USA as of year 2010?

20.What changes has white population undergone according to the results of 2010 US census?

NATIVE AMERICANS

The marks of the cultural heritage of American Indians can be found all over the United States. Many of the names on U.S. maps—Massachusetts, Ohio, Michigan, Kansas, Idaho and more—are Indian words. The Indians taught the Europeans how to cultivate crops such as corn, tomatoes, potatoes and tobacco. Canoes, snowshoes and moccasins are all Indian inventions. Indian handcrafted artifacts such as pottery, silver jewelry, paintings and woven rugs are highly prized.

About half of the Indians in the United States live in large cities and rural areas scattered throughout the country. The rest live on about 300 federal reservations (land set aside for their use). Together, the reservations comprise about 20 million hectares of land (about 2.5 percent of the land area in the U.S.). Most reservations are located west of the Mississippi River.

The transfer of land from Indian to European—and later American—hands was

accomplished through treaties, war and coercion. It was accompanied by a long struggle between the Indian and European ways of life. In many ways, the history of the United States is the story of this struggle.

Who were the Indians?

In 1492, an Italian navigator Christopher Columbus set sail from Spain in search of a sea route to Asia. Six weeks later, his men sighted land.

Thinking he had landed in the Indies, a group of islands east of the coast of Asia, he called the people on the first island on which he landed "los Indios," or, in English, "Indians." And historically the group of islands in the Caribbean Sea, the Bahamas, and the Turks and Caicos Islands were also known as West Indies.

Of course, Columbus had not reached Asia at all. He had landed in the New World (the American continent). But the name "Indians" remains fixed in the English language. And the group of islands

Though Columbus had one name for them, the Indians comprised many groups of people. The Indians north of Mexico in what is now the United States and Canada spoke over 300 languages. (Some 50 to 100 of these languages are still spoken today.) And they lived scattered across the continent in small bands or groups of bands called tribes. To them, the continent was hardly new. Their ancestors had been living there for perhaps 30,000 years.

Scientists speculate that people first came to North America during the last ice age. At that time, much of the earth's water was frozen in the glaciers that covered large parts of the globe. As sea levels dropped, a strip of land was exposed in the area that is now the Bering Strait. Man probably followed the big game he was hunting across this land bridge from Siberia into Alaska.

Over time, these people increased in number, adapted to different environments and spread from the far northern reaches of Alaska and Canada to the tip of South America.

Some groups, such as the peaceful Pueblo of the American Southwest, lived in busy towns. They shared many-storied buildings made of adobe (mud and straw) bricks. They grew com, squash and beans.

Their neighbors, the Apache, lived in small bands. They hunted wildlife and gathered plants, nuts and roots. After acquiring horses from the Spanish, they made their living by raiding food and goods from their more settled white and Indian neighbors.

In the eastern woods of the North American continent, the Iroquois hunted, fished and farmed. Like the Pueblo, they were excellent farmers, and 12 varieties of corn grew in their communal fields. Their long houses, covered with elm bark, held as many as 20 families. Each family had its own apartment, on either side of a central hall.

The Iroquois were fierce warriors. They surrounded their villages with wooden stockades to protect them from attack by their neighbors. They fought for the glory of their tribe and for the glory of individual warriors.

The Indians of the North Pacific coast harvested ocean fish and seafood. Tribes like the Haida lived in large plank houses with elaborately carved doorposts. These were called totem poles, and the figures on them were a record of the history of the family which lived in the house.

Many Indians were fine craftsworkers. They made pottery, baskets, carvings and wove cotton and plant-fiber cloth. They traveled in small boats and on foot, never having developed the wheel. Some, such as the Plains Indians, used dogs to pull a load-carrying frame called a travois. Others, such as the Winnebagoes of the Midwest developed a sophisticated calendar that took the motions of both the sun and the moon into account.

Different as they were, all tribes were greatly affected by the coming of the white man, with his firearms, iron cooking pots, horses, wheeled vehicles and with his diseases, to which the Indians had no immunities. The European arrival changed the Indian way of life forever.

Early encounters

Most often the Europeans came to establish new homes in North America; they came to farm. And for that they needed land. At first, the Indians were glad to share their land and their food with the Europeans. The American holiday of Thanksgiving celebrates this Indian generosity. The first to celebrate it were the Pilgrims, a group of English settlers who arrived in America in 1620. They gave thanks for having survived their first year in the harsh American wilderness. But there would have been no Thanksgiving had it not been for the Indians.

The Pilgrims arrived on the shores of Massachusetts in November and survived their first winter with help from the Wampanoag and Pequamid Indians who shared corn with them, and showed them where to fish. Later, they gave seed corn to the English settlers and showed them how to plant crops that would grow well in the American soil.

The quest for land

To the Europeans, much of the Indians’ land appeared vacant. The Indians didn't "improve the land" with fences, wells, buildings or permanent towns. Many settlers thought the Indians were savages and that their way of life had little value. They felt they had every right to farm the Indian lands.

On Manhattan Island, the present site of New York City, beaver, deer, fox, wild turkey and other game (wild animals) were plentiful. The Shinnecock Indians used the island for fishing and hunting, but they didn't live there. In 1626, the Dutch "bought" the island from them. The Shinnecock did not understand that once the land was sold, the Dutch felt it was their right to keep the Indians off. Like most Indians, they had no concept of private property.

The Indians believed that the land was there to be shared by all men. They worshipped the earth that provided them with food, clothing and shelter. And they took from it only what they needed. They didn't understand when the settlers slaughtered animals to make the woods around their towns safer. They didn't like the roads and towns that to them, scarred the natural beauty of the earth.

To the Europeans, game existed to be killed and land to be owned and farmed. Many did not bother to discuss with the Indians whether or not they wanted to give up their land. To make room for the new settlers, hunting lands, fields, even Indian towns were seized through war, threats, treaties or some combination of the three.

Western Frontier

At the time of the American Revolution, the western boundary of the United States was the Appalachian Mountains. Land had become expensive in the colonies and many people were eager to settle the wilderness that lay beyond those mountains.

The Indians fought these invaders of their hunting grounds with a vengeance. Indian warfare quickly became a part of frontier life.

The United States tried different ways of dealing with their "Indian problem." Basically, they all boiled down to this: The Indian had to be either assimilated or removed farther west to make room for the European civilization the white Americans felt was destined to rule the continent.

In 1830 the United Slatespassed the Indian Removal Act. All Indians in the East would be removed to lands set aside for them west of the Mississippi River.

One of the tribes slated for removal was the Cherokee. Ironically, the Cherokee had already adopted many of the white man's ways.

The peaceful Cherokees were removed by force from their homes and forced to march overland to Indian Territory, in what is now the state of Oklahoma. The difficult journey took three to five months. In all, some 4,000—one quarter of the Cherokee nation—lost their lives in the course of this removal. This shameful moment in American history has come to be called "The Trail of Tears."

The reservation system

By 1890, almost all of the West, from the prairies to the Pacific, had been settled by cattle ranchers, farmers and townspeople. There was no more frontier, no mountains beyond which the Indians could live undisturbed. Most were confined to reservations. The government had promised to protect the remaining Indian lands. It had also promised supplies and food. But poor management, inadequate supplies and incompetent or dishonest government agents led to great suffering on the reservations. Diseases swept through the tribes and for a while it seemed as though the Indians really were a vanishing race.

By the General Allotment Act of 1887, each Indian was allotted 160 acres to farm. But there was no magic in owning private property. Many Indians had no desire to farm. Often, the land given them was unfertile. After each Indian was given his plot, the government sold the remaining lands to white settlers. The result was disastrous: By 1934, Indian land holdings had been reduced from 56 million hectares to 19 million hectares.

A new deal for the Indians

In 1924, Congress passed the Indian Citizenship Act, which declared all Indians born within the territorial limits of the United States to be citizens.

However, it wasn't until 1934 that the Indians got a "New Deal." The Indian Reorganization Act encouraged the Indians to set up their own governments and ended allotment on the reservations. It stopped the policy of trying to persuade or coerce Indians to give up their traditional culture and religion.

The United States was becoming proud of its diverse population. And that included a desire to recognize its Native Americans and to try to compensate them for the unfair treatment they had received.

An uphill battle

At a time when blacks were protesting violations of their civil rights. Indians, too, took their protests to the American public. In 1972, the American Indian Movement (AIM) staged a protest march on Washington called the 'Trail of Broken Treaties." Indians today continue to fight for Indian rights.

But in spite of many gains made by the Indians, they still lag far behind most Americans in health, wealth and education. The unemployment rate on Indian reservations is high. And many of Native Americans live below the poverty line. Diabetes, pneumonia, influenza and alcoholism claim twice as many Indian lives as other American lives.

Since the 1950s, the government has helped Indians who want to move from the reservations to cities. A few have found highly paid jobs in business, education, law and medicine. But most urban Indians still lack the education and job training to find skilled jobs. Many end up trading rural poverty for urban slums.

Life on the reservations varies greatly. The Navajo reservation, located in parts of three states in the Southwest, is the nation's largest. It is also one of the poorest. Many reservation homes lack electricity and plumbing. The reservation has few towns and few jobs.

In contrast, the Mescalero Apache reservation nearby in New Mexico is one of the nation's wealthiest. The tribe owns and operates a logging company and a cattle ranch. Both are multimillion dollar businesses. Most who want to work do. Presently, white managers help to run some of their businesses. But the aim of the Apaches is independence—they hope to take over management of all of their own programs.

RELIGION

A pilgrim people

For over a thousand years, Roman Catholic Christianity had been the religion of most of Europe. But by the 16th century, many people had grown to resent the richly decorated churches and ornate ceremonies of the Catholic Church. They resented the power of the Pope, the head of the Catholic Church, as well as the bishops, many of whom lived as magnificently as civil rulers.

Early in the 16th century, Martin Luther, a German monk, broke with the Catholic Church. Luther's teaching emphasized direct personal responsibility to God, challenging the role of the Church as an intermediary. A few years later, John Calvin, a French lawyer, also left the Catholic Church. One of his basic concepts was the idea of God as absolute sovereign, another challenge to the Church's authority.

As a result of their protesting of widely accepted teachings, Luther, Calvin and other religious reformers soon became known as Protestants. Their ideas spread rapidly through northern Europe. Soon established Protestant Churches had arisen in several European lands.

The modern concept of religious tolerance was not widespread. People were expected to follow the religion of their king. Catholics and Protestants fought each other and many religious people on both sides died for their beliefs

In England, King Henry VIII (1491-1547) formed a national Church with himself as its leader. But many English people considered the Church of England too much like the Catholic Church. They became known as Puritans, because they wanted a "pure" and simple Church. The ideas of John Calvin particularly appealed to these Puritans.

When James I (a Catholic) became King of England in 1603, he began to persecute the Puritans. Many went to prison or left the country. The Puritans could not always agree among themselves either. Many small Puritan groups formed in England. The Pilgrims who went to the New World belonged to one of them.

As religious believers, the Pilgrims had formed a congregation, or small group of church members, by joining themselves together and choosing a minister. They did this through a contract, and they considered such congregations the basic unit of the Church.

When the Pilgrims assembled on their ship, the Mayflower, they formed a government in the same way they had formed their congregation. They made a contract, which became known as the "Mayflower Compact."

With this contract, they agreed to form a "civil body politic" which could make "just and equal laws" for the colony. Most of the grown men of the group signed the compact. Then they began the search for a place to build their homes.

Other Puritans soon followed the Pilgrims to Massachusetts and established towns there. Like other Protestants, they read the Bible often and claimed the right to interpret or explain the meaning of the Holy Book for themselves. The Puritans were particularly interested in the Old Testament.

The Old Testament describes the history of the Jewish people as a contract between God and Israel. God's contract with the Jewish people was the model for the covenants by which the Puritans formed their congregations. The Puritans thought of themselves as a special people. "We shall be as a city upon a hill," wrote John Winthrop, (1588-1649) another Puritan leader. "The eyes of all people are upon us."

Like other followers of Calvin, the Puritans considered worldly success a sign of being saved. They considered their increasing prosperity a sign that God was pleased with them. They generally assumed that those who disagreed with their religious ideas were not saved and therefore should not be tolerated.

In 1636, Roger Williams (1603-1683) was forced out of Massachusetts for disagreeing with the ministers there. He founded a colony in what later became the state of Rhode Island. Rhode Island allowed religious freedom to everyone, and it became a refuge for people persecuted for their religion.

Two other American states began as heavens of religious freedom. Maryland was founded as a refuge for Catholics. And Pennsylvania was founded as a refuge for Quakers, a religious group which adopted a very plain way of life and refused to participate in war or to take oaths.

Religious liberty

The First Amendment to the Constitution of the United States forbade the new federal government to give special favors to any religion or to hinder the free practice, or exercise, of religion. But Protestant Churches kept a privileged position in a few of the states. Not until 1833 did Massachusetts cut the last ties between Church and State.

In some ways, the government supports all religions. Religious groups do not pay taxes in the United States. The armed forces pay chaplains of all faiths. Presidents and other political leaders often call on God to bless the American nation and people. Those whose religion forbids them to fight can perform other services instead of becoming soldiers.

But government does not pay ministers' salaries or require any belief—not even a belief in God—as a condition of holding public office.

The truth is that for some purposes government ignores religion and for other purposes it treats all religions alike—at least as far as is practical. When disputes about the relationship between government and religion arise, American courts must settle them.

American courts have become more sensitive in recent years to the rights of people who do not believe in any God or religion. But in many ways what Supreme Court Justice William O. Douglas wrote in 1952 is still true. "We are a religious people," he declared, "whose institutions presuppose a Supreme Being."

In the early years of the American nation, Americans were confident that God supported their experiment in democracy. They had just defeated Great Britain—probably the most powerful nation in the world at that time. Protestant religion and republican forms of government, they felt, went hand in hand. America had a divine mission to make her unique combination of political freedom and "Yankee" thrift and ingenuity a model for the world to follow.

Religious diversity

Since Americans are free to form and follow any religious belief or religion they wish, there are a great many beliefs, denominations, and churches in the United States. The Roman Catholic church and various Protestants churches have the biggest numbers of followers.

Although there is no longer even the assumption that America is, or should be, "a white, Anglo-Saxon, Protestant" (WASP) nation. Yet surveys show that religion continues to be quite important to many Americans, especially when compared with people in other countries.

The United States has always been a fertile ground for the growth of new religious movements. Small sects and "cults" do have certain tendencies in common. Often they regard the larger society as hopelessly corrupt. Prohibition of alcohol, tobacco and caffeine are common. Sometimes predictions of the end of the world form the main doctrines of the group. Often the founder is a charismatic person, a dynamic personality who claims some special revelation or relationship with God.

Some of religious groups are:

the Amish, very strict Protestants who live in rural areas and scorn modern life. They wish to keep their children out of high school so they will not be affected by modern society;

Jehovah's Witnesses;

the Mormons are one of the fastest growing church groups in the United States.

Other world religions are increasing their numbers and influence in America too. There are followers of Judaism and the Islamic religion. Buddhism is a growing faith in America.

Most Americans are proud of America's religious variety. They consider it a natural result of religious freedom. On public occasions they stress the ideas most religious people share— belief in God and the importance of living a good life.

A Nation of Immigrants

The United States has often been called "a nation of immigrants." There are two good reasons for this. First, the country was settled, built, and developed by generations of immigrants and their children. Secondly, even today America continues to take in more immigrants than any other country in the world. It is not surprising, therefore, that the United States is counted among the most heterogeneous societies in the world. Many different cultural traditions, ethnic sympathies, national origins, racial groups, and religious affiliations make up "we the people."

The "Average American"

The variety of ethnic identities, immigration experiences, and cultural choices that have gone into making Americans is so complex, however, that describing the "average American" is very difficult.

The United States is one of the few countries that has no "official" national language, or languages. English is the common language by use, but it is not the national language by law.

The "Melting Pot," the "Salad Bowl," and the "Pizza"

Of all the many different nationalities and ethnic groups which have gone into the making of America, somehave quickly assimilated. They have largely lost or intentionally given up many of those specific markers which would make them much different from their neighbors. This process of assimilation, or "Americanization," - becoming part of the "melting pot" - has characterized the immigrant experience in American history. Other Americans have, while becoming American in other ways, maintained much of their ethnic identities. In this sense, U.S. society has been likened to a "salad bowl." It does not follow, however, that these Americans are any less aware or proud of their American nationality. Perhaps a better metaphor for American society than either "the melting pot" or the "salad bowl" would be that of a "pizza" (which has become, by the way, the single most popular food in America). The different ingredients are often apparent and give the whole its particular taste and flavor, yet all are fused together into something larger.

Still another factor to consider in describing "the American" is that the face of America is constantly, and often very rapidly, changing. It is estimated that by the year 2000, for instance, Hispanics (a term including all Spanish-speaking Americans, such as Mexican-Americans or "Chicanos," Cubans, Puerto Ricans, etc.) will be the largest "minority" in the United States. In a number of cities Hispanics will represent the majority of citizens.

Crevecoeur's old and often repeated question -"What then is the American, this new man?" -cannot be answered simply or conclusively. At best, we can say that an American is someone who meets the legal requirements of citizenship and who considers himself or herself to be an American. And, any person born on American soil automatically has the right to American citizenship. Significantly, the older categories of nationality brought from the Old World - race, language, religion, and parents’ ancestry - have become relatively unimportant in America. They can be used lo describe an American, but not to define one.

Changing Patterns of Immigration

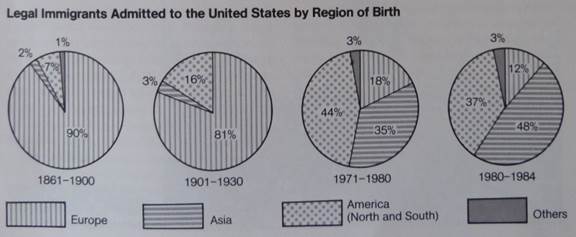

Where Americans came from and when they came, does not define how they see themselves today. It is interesting to see, though, how the - immigration patterns have changed over lime.

These changing patterns do affect, and have affected, what America is today and how Americans view the rest of the world.

Between 1861 and I960, the majority of immigrants came from Europe. But during the past 25 years the largest share of immigrants has come from Latin America and Asia. In 1984, for instance, 64,100 immigrants from Europe were legally admitted to the U.S. By contrast, legal immigration from the southern Americas (mainly Mexico, the West Indies, the Dominican Republic, and Colombia) was 193,500. An additional 256,300 legal immigrants came from Asia (mainly the Philippines, Vietnam, Korea, and China).

The millions of "de facto Americans" - and no one knows exactly how many there really are - are not included in the figures shown above. The Census Bureau estimates that there are usually three to six million "illegal immigrants" already living in the U.S., about two-thirds of them from Mexico. What is very clear is that the so-called European heritage of America is undergoing a major change as more and more people from Latin America and from Asian countries enter U.S. society. Growing numbers of Americans will be able to say that they, or their parents or grandparents, came from these regions. As a consequence, the American view of the world is more likely to be towards the south and west.

Immigration Laws

Some of these changes have been brought about by changes in the immigration laws. Until the 1850s, immigration to the U.S. had been largely unrestricted, with some 90 percent of all immigrants coming from Europe. In the 1920s, a number of measures were taken to limit immigration, especially from Asian countries and southern and eastern Europe. The overall number of immigrants was limited by law and quotas were set for countries and, later, "hemispheres." In 1968, this quota system was abolished. An annual limit of 170,000 was set for immigrants from the Eastern Hemisphere and 120,000 for the Western Hemisphere. Ten years later, the separate limits for the two hemispheres were abolished in favor of a worldwide limit of 290,000 per year. In addition, however, special measures were taken to allow large numbers of refugees from several regions (especially East Asia and Central and South America) to enter the U.S. Thus, the average number of immigrants legally admitted throughout the 1970s was about 430,000 per year. The number jumped to 654,000 in 1980, reflecting a new wave of Cuban refugees. In recent years, the number of immigrants officially admitted to the U.S. was around 550,000 per year.

Why They Came - Why They Come

Major changes in the pattern of immigration have been caused by wars, revolutions, periods of starvation. persecutions, religious intoleration, and. in short, by any number of disasters which led people to believe that America was a better place to be. More than a million Irish, for instance, emigrated to America between 1846 and 1851 in order to escape starvation and disease in Ireland. During the same period, large numbers of other Europeans fled political persecution. And in the 1870s another wave of refugees left the political turmoil of eastern and southern Europe to seek freedom and a future in America. The largest streams of European immigrants came between 1900 and 1920, that is, before, after, and during World War I. At other times, for example, during the Depression and during World War II, smaller numbers of immigrants came to the U.S. Since the 1960s, more and more people have fled the poverty and wars in Asia and Latin America in the hope of finding a better life in the United States.

The moral questions associated with immigration remain today. The large number of illegal immigrants pouring over the long Mexican border, for example, has led some Americans to call for much stronger restrictions. Yet many of these illegal aliens were living in poverty that is shocking even to the poorest Americans. If you are an American whose ancestors were poverty-stricken, saying "no" to such people is very difficult. On the one hand, this immigration provides a safety valve for Mexico. On the other hand, admittedly, some Americans welcome this source of inexpensive labor. In any case, stopping the vast flow of illegal immigrants is much easier to demand than to do. Whether they are wanted or not, they continue to come. Even as the countries of origin and patterns of immigration change, America's tradition as a nation of immigrants is not likely to end.

All in all, the heritage of immigrants and immigration has brought enormous benefits to America. Without a doubt, the American immigration experience, then and now, is one of the most important factors in American life. All immigrants have contributed to the development of some "typical" American characteristics. Among these are the willingness to take risks and to strike out for the unknown with independence and optimism. Another is patriotism for the many who feel that they are Americans by choice. And, equally, there is the self-critical tradition; those who were "fat and happy," as the phrase goes, never left home.

Дата добавления: 2015-10-29; просмотров: 222 | Нарушение авторских прав

| <== предыдущая страница | | | следующая страница ==> |

| Программирование апплета | | | Demographics-the Basic Picture |