Читайте также:

|

Jack Goldstone, Andrey V. Korotayev, Julia V. Zinkina

Fertility decline has stalled in numerous Sub-Saharan countries since the late 1990s and early 2000s, while mortality decline has continued and recently sharply accelerated; the resulting youth surge, hyper-urbanization, and anticipated population increases are bringing very high risks of socio-political collapse and humanitarian catastrophe in this region. If current demographic trends persist the population of, say, Nigeria may well exceed, by the end of this century, five times the population of Russia, a level that is fraught with risks of social and political collapse. As many sub-Saharan countries are on a similar trajectory to achieve new orders of magnitude in population, such collapses, if not averted by drastic policy changes, may attain a truly global scale, with death tolls as large as tens or even hundreds of millions.

However, these risks are avoidable. The most important preventive measure is INTRODUCING GENERAL COMPULSORY SECONDARY EDUCATION as soon as possible. This will help to decrease the demographic burden through two ways, namely accelerating the fertility decline, and increasing economic growth rates. Undoubtedly, introducing compulsory secondary education is a very expensive measure, and most of the sub-Saharan countries at risk will be unable to manage it on their own. Thus, it is utterly necessary for the international community to provide support to Sub-Saharan countries in this respect, and to ensure the funds are properly spent. This implies a substantial increase in financial aid destined for these goals, and expansion of country agreements with the World Bank to fight corruption. If this support is not provided promptly, much greater expenses will invariably be required later on to deal with sociopolitical catastrophes in the sub-Saharan countries.

According to the latest medium forecast by the UN Population Division, the population of such relatively middle-sized East African countries as Kenya and Uganda will exceed the population of Russia in the second half of the century. Tanzania will reach Russia in terms of population by 2050 and is projected to have twice the Russian population by 2100. Nigeria’s population will be five times bigger than the current population of Russia by the end of the century (Fig 1)!

Fig. 1. UN Population Division medium population forecast for selected sub-Saharan countries, thousands. Black dotted line presents the current population of Russia for comparison.

Such explosive population forecasts are not the extreme projections, but assume substantial declines in fertility in coming decades. The UN medium variant assumes that in Nigeria, for example, fertility will fall from 5.4 children per woman in 2010-2015 to 3.2 by 2050 and 2.2 by 2100. If fertility were to remain constant at 2010 levels, the projected population of Nigeria would reach over 1 billion by 2075 and 2.66 billion by 2100, obviously impossible numbers. Yet even in the UN’s “high variant” projection for Nigeria, which also assumes a decline in fertility to 3.7 by 2050 and 2.7 by 2100, the forecast total population for Nigeria reaches over 500 million in fifty years, and over 1 billion by 2100.

The UN ‘medium’ forecast is thus a fairly conservative projection that assumes continued and rapid fertility decline. A more moderate fertility decline produces the “high variant’ projections which are even more alarming. In the 1990s, when fertility was falling rapidly everywhere in the world, including sub-Saharan Africa, the assumption that fertility in Africa would continue to fall steadily and rapidly toward replacement levels was reasonable. While mortality would fall as well, the more rapid decline in fertility was expected to continually lower the growth rates of these countries. Yet as we shall discuss in more detail below, since 2000 it has become apparent that fertility is not falling as fast as expected in much of sub-Saharan Africa. In fact, in many countries fertility decline has slowed drastically or stalled altogether. At the same time, advances in treating childhood infections, HIV-AIDS, and parasitic diseases have greatly increased survival rates. As a result, in recent years population growth rates in many countries have stabilized at still-high levels, or even slightly increased.

Fig. 2 presents the UN’s latest medium variant forecasts for total population for several low-income sub-Saharan countries with relatively weak, ineffective governments, and thus high risks of political and humanitarian disasters (today’s population in Russia is given as a reference for comparison):

Fig. 2. Sub-Saharan countries with high risks of encountering a large-scale humanitarian catastrophe in the 21st century – UN medium forecast population (in thousands).

The case of Malawi is particularly astonishing, as it is supposed to accommodate the current population of Russia on a territory of about 100,000 sq. km (approximately the territory of the U.S. state of Nevada). Equally astonishing is the projection for Nigeria: if its fertility does not fall even more rapidly than in the UN medium projection, Nigeria’s population will exceed the total population of all of Europe (including Russia) by the end of the century. It is hard to see how Malawi, Nigeria and other countries in the region can avoid social and political disasters if this explosive population growth is not curbed.

Because the medium UN forecast is in no way inertial – in other words, it is not based on a simple continuation of the current demographic trends, but on the contrary, implies a very significant acceleration in fertility decline as compared to the recent years – it should be seen as already implying favorable policies to promote fertility decline. Fig. 3 displays the fertility declines used as assumptions for the UN medium variant forecast for several sub-Saharan countries. These show a marked acceleration in the rate of fertility decline from 1995-200 levels, starting in 2003 in the DRC and Uganda, and in 2017 in Niger.

Fig. 3. Fertility decline assumptions used in UN medium forecast to 2030 for selected Sub-Saharan countries.

What is worrisome is that even with such considerable acceleration of fertility decline, the population projections for most sub-Saharan African countries remain so high as to invite disaster. Thus the fertility declines in the UN medium variant are absolutely insufficient for the prevention of humanitarian catastrophes.

Historically, sustained population increases in agrarian nations have led to a cluster of effects that produced political upheavals (Goldstone 1991). These include increases in prices of basic commodities and declining real wages and employment; heightened competition for land, work, and elite positions leading to intergroup and political conflicts; and increasing fiscal and administrative burdens and revenue shortfalls that undermined governments.

The situation is exacerbated with many of the sub-Saharan countries still being vulnerable to the Malthusian trap, with a large portion of the population dependent on agriculture and yet not producing sufficient food for the urban and working population which thus depends on food imports, a situation which greatly increases the risks of socio-political collapses in these countries (Korotayev, Khaltourina 2006; Korotayev et al. 2011). Indeed, approximately half of sub-Saharan countries hardly achieve the WHO recommended norm of daily per capita calorie intake, or fall far below this norm, sometimes balancing on the verge of famine. Such situations have often led to socio-political collapses and even violent civil wars in various countries in the past. Sub-Saharan countries are struggling to increase per capita food consumption, as huge population growth literally “eats up” their productivity growth, especially in the agricultural sector. With things being this hard now, with the population projected to increase by several times over in the coming decades, any major shocks to food supplies may very likely lead to full-scale famines and humanitarian disaster.

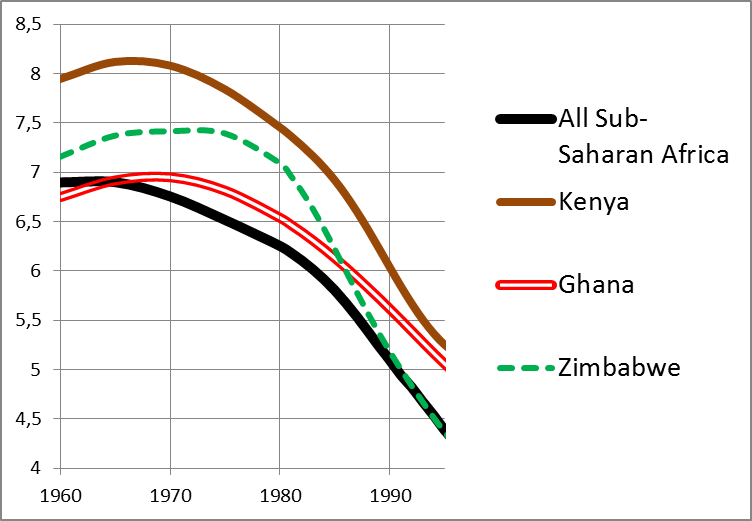

However, despite the acuteness of the explosive population growth problem and the obvious necessity of immediate action to reduce fertility rates in sub-Saharan Africa even more rapidly than in the U.N medium forecasts, fertility has been left out of the focus of attention by the major international aid donors. Indeed, the peak of alarmist perceptions of the demographic explosion in Sub-Saharan Africa was observed in the global community from the 1970s to the early 1990s (see, e.g.: Ehrlich 1968; P. R. Ehrlich, A. H. Ehrlich 1990). Notably, during that very period fertility rates in most Sub-Saharan countries started to decline faster and faster, as shown in Figure 4:

Fig. 4. Total fertility rate dynamics in some Sub-Saharan countries, 1960 – 1995.

By the early 2000s the global community had become well aware of the increasingly fast fertility decline proceeding in sub-Saharan Africa. UN experts forecast the sub-Saharan population to become stable at relatively safe levels (see Fig. 6 below). The international community therefore became more or less “calmed down” (see, e.g., UN Population Division 1998, especially Fig. 1.9; Cohen 1999a, 1999b, 2002: 46–47). A widespread opinion prevailed that having once started, fertility decline would proceed rapidly and uninterruptedly until fertility reached the replacement level of 2.1.

After the Cairo international conference of 1994, the priority focus of international concern shifted from family planning programs to the issues of reproductive health, women’s participation in decision-making, etc. (see, e.g., Blanc, Tsui 2005; Cleland et al. 2006). The priority change was followed by many family planning programs being closed (including one by DfID). The volume of international financial aid to family planning programs decreased substantially between 1995 and 2003 (UN Economic and Social Council 2004).

Moreover, a powerful “rival” emerged in the mid-1990s to family planning programs, namely the HIV/AIDS pandemic, which had by that time acquired a threatening scale and pulled in considerable international attention and financial resources. Indeed, according to some estimates, the proportions of donor aid given to family planning and anti-HIV programs were respectively 54% and less than 10% in 1995, while by 2007 these shares changed to less than 5% and more than 85% respectively (Ezeh, Mberu, Emina 2009).

However, this “calming down” appears now to have been quite premature. In the late 1990s and the early 2000s the fertility decline in many Sub-Saharan countries experienced a large-scale stall; in some countries fertility even started to grow again. This was even more ominous as fertility stalled at relatively high rates: only in a few countries had the fertility rate dropped below 5 children per woman before the stall began. In the majority of countries fertility stalled at 5.5 to 6 children per woman (see Fig. 5):

Fig. 5. Total fertility rates in selected sub-Saharan countries, 1990 – 2005

Taking into account the fertility stall, UN experts have had to revise their population forecasts for Sub-Saharan countries, increasing the expected population to numbers which imply high risks of large-scale humanitarian disasters if no adequate measures are taken in the very near future to prevent this explosive population growth (see Fig. 6):

| Nigeria | Tanzania |

|

|

| Zambia | Malawi |

|

|

Fig. 6. Comparisons of medium population forecasts made by the UN in 2000 and 2012 for selected sub-Saharan countries, in thousands. Sources: UN Population Division 2001, 2012.

As a result of fertility stalling at high levels in many Sub-Saharan countries, and the priority shift in international aid distribution from family planning to HIV/AIDS, the risk of large-scale humanitarian disasters is much higher now than it used to be 10 years ago. Meanwhile, the global community still has not recognized the reappearance of the threat of socio-political catastrophes in sub-Saharan Africa if rapid fertility decline does not resume very soon.

So, what can be done before it is too late to prevent the threat?

Education

Female education is a critically important factor influencing fertility levels (e.g., Korotayev, Malkov, Khaltourina 2006). Increasing female education rates brings down both real fertility and the desired number of children. More educated women tend to marry later (which is a strong predictor of fertility decline in traditional societies with low contraception prevalence and socio-cultural norms suppressing extramarital fertility), are more informed about contraception and have better access to it, and tend to use family planning more often and more effectively (Caldwell, 1980; United Nations, 1987; Jejeebhoy, 1995; Caldwell, 1997; Uchudi, 2001; Kirk & Pillet, 1998). However, in sub-Saharan Africa the effect of education increases on fertility decline was less pronounced than in other regions of developing world, probably due to comparatively very low levels of female education in the past decades (Cochrane & Farid, 1986; Cleland & Rodriguez, 1988; van de Walle & Foster, 1990; Rodriguez & Aravena, 1991).

A number of later works have substantially proved the significant impact of spreading female education in sub-Saharan Africa on fertility decline. Bongaarts analyzed a sample of 30 sub-Saharan countries and found a robust negative association between the TFR and education level: “The TFR among women with secondary and higher education is lower than for women with primary education in all 30 countries, and the TFR of women with primary education is lower than for women with no education in 27 countries” (Bongaarts 2010: 7).

The global community has by now acknowledged the necessity of disseminating education in sub-Saharan countries. One of the Millennium Development Goals states the necessity of achieving universal primary education by 2015. However, in this discourse education is usually regarded by itself, its influence upon fertility being left out of the picture.

Let us view how the achievement of this MDG, namely the provision of universal primary education, is likely to impact the TFR in Sub-Saharan countries. We have carried out a regression analysis of the relationship between the share of women aged 15+ having at least incomplete primary education and TFR according to the Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS) data for 35 Sub-Saharan countries foe various years (the majority of countries had more than one DHS carried out) (see Fig. 7):

Fig. 7. Correlation between the share of women aged 15+ having at least incomplete primary education and TFR in Tropical Africa (excluding countries of South Africa). Scatterplot with a fitted regression line.

r = –.42, p < 0.001

Our analysis allows drawing an important conclusion: a simple elimination of female illiteracy (100% women having at least incomplete primary education) is utterly insufficient for bringing sub-Saharan fertility rates down to the replacement level. Regression analysis reveals that if all sub-Saharan women attain at least incomplete primary education (but with most of them remaining without secondary education), TFR is only likely to reach a level of slightly higher than 5 children per woman.

The insufficiency of primary education to drastically reduce fertility is supported by various case studies as well. Thus, Gupta and Mahy applied multiple logistic regression methods to the analysis of 8 sub-Saharan countries (Burkina Faso, Cote d’Ivoire, Ghana, Kenya, Mali, Senegal, Tanzania, and Zimbabwe) for the time period 1987–1999 to study the impact of various female education levels upon fertility. They came to conclude that “girls’ education from about the secondary level onwards was found to be the only consistently significant covariate” having consistent negative impact upon fertility and the age at first birth (Gupta, Mahy 2003).

Now let us view the impact of secondary education dissemination upon fertility levels in Sub-Saharan Africa (Fig. 8):

Fig. 8. Correlation between proportion of females aged 15+ with at least incomplete secondary education and TFR in Sub-Saharan countries. Scatterplot with a fitted regression line.

r = –.757, p <.001.

The correlation here is obviously much stronger than the one for primary education and TFR. Even more importantly, the regression analysis indicates that at 70% female enrolment in secondary education the TFR in sub-Saharan countries is likely to reach replacement level.

However, we should emphasize here that preventing the risks of socio-political disasters in sub-Saharan Africa through increasing the secondary education rate among females aged 15+ up to 70% is not as simple as it might seem at first sight. Actually, it cannot be achieved by simply bringing net enrolment rates to 70% (making 70% of African girls of secondary school age attend secondary school) – which in itself is a complicated task to accomplish, achievable only with strong political will and substantial financial resources. The main problem is that the majority of sub-Saharan women in fertile ages not having secondary education are far out of the school age. Providing secondary education for, say, 70% of illiterate women aged 30+ seems to be an unrealistic scenario, and we cannot regard it seriously. Naturally, opportunities for adults to receive secondary education should be developed as well. However, the first and foremost way of increasing the proportion of women with secondary education is securing a 100% secondary school enrollment rate for all children of relevant ages, especially for girls.

Thus, in order to prevent major socio-political catastrophes, sub-Saharan countries should introduce universal compulsory secondary education as soon as possible. Even this measure will not increase the proportion of females with secondary education fast enough – even if compulsory secondary education is introduced immediately[1], a significant increase in the secondary education rate among females aged 15+ will only be observed with a considerable lag of 8–12 years (depending on the length of primary and secondary education)[2].

Nonetheless, this is still timely enough to have a major effect on population growth to 2050, and even more so on growth to 2100. This measure will help to decrease demographic pressure on the economy and society in two ways – first, bringing down fertility rates; second, accelerating economic growth (through the demographic bonus and increasing the labor productivity growth; see, e.g. Korotayev 2009).

The introduction of universal compulsory secondary education in sub-Saharan Africa is, naturally, a tremendously expensive measure, and most sub-Saharan countries will be unable to manage it on their own. It is unusually labor intensive (although this is a good thing in one respect, as it will increase employment). It is fortunate that at this very moment the technology for producing and disseminating world class educational materials via the internet is maturing and becoming far less costly. Nonetheless, it is utterly necessary for the international community to provide increased support to sub-Saharan countries for the specific goal of increasing secondary school education throughout their populations, which implies a substantial increase in financial aid destined for these goals[3].

If this support is not provided in the immediate future, much greater expenses will be invariably required later on to deal with the political and humanitarian catastrophes that will result from runaway population growth in sub-Saharan countries.

Дата добавления: 2015-10-26; просмотров: 138 | Нарушение авторских прав

| <== предыдущая страница | | | следующая страница ==> |

| An expression of worth | | | African Quotes on Food |