|

Читайте также: |

Yet southerners in Congress and at home were unsure about how far to go. In the states where expansion mattered most, the debate over whether or not to send delegates to the Nashville Convention—and which delegates to send—ran white hot during early 1850. At the same time, pro-compromise meetings sprang up across the South. Many southern whites weren’t ready for secession, which was what the extremists suggested. When the Nashville Convention gathered on June 3, far fewer delegates were present than radicals had anticipated. None came from Louisiana, and only one from Texas. Clay’s compromise would pay off Texas debts, many of them held by Louisiana-based creditors.46

There was still hope for a Washington compromise. Months of debate had passed with little change in positions, but time moved the pieces on the board all the same. Calhoun, exhausted, died on March 31, depriving the southern radicals of the one figure who could have welded them into a weapon. Clay’s increasingly bitter confrontation with Taylor, whose “treachery” to southern enslavers had helped fire up radicalism in Congress and in the southern press, ended on July 5, when the president suddenly died. Vice President Millard Fillmore, an upstate New Yorker with close ties to Clay, succeeded the maverick Taylor. The Whigs still could not unite behind Clay’s bill, however, and the Senate defeated it at the end of July. The Nashville Convention delegates, sitting by the telegraph, had nothing to reject.

To judge from his letters to his wife, Clay had spent all spring basking in premonitory adulation.

Now he gave up on compromise and fled north to Newport, Rhode Island, his favorite resort town, where the spent old man could play cards, bet the ponies, and flirt. Back in Washington, a new force, Illinois Democratic Senator Stephen Douglas, appointed himself the floor general of compromise. Separating the omnibus into its constituent parts, he deftly assembled a series of coalitions— southerners and a few northerners for the pro-southern aspects, the opposite for elements like the admission of California as a state—and pushed the compromise through the Senate as multiple bills. At the beginning of September, he drove the Senate bills through the House, from whence they were sent back to the Senate for reconciliation. On September 20, almost ten months after the Thirty-First Congress had first been seated, Fillmore signed the compromise bills into law. Cannons boomed in Washington, DC. Crowds outside of boardinghouses and hotels serenaded the congressional leaders, who were inside drinking themselves into stupors of relief.47

In communities like Springfield, Illinois, newspapers called for “national jubilation.” The New Orleans Picayune said the territorial question was “definitely settled.” In December, in his message to Congress as it opened a new session, President Fillmore referred to the Compromise of 1850 as “in its character final and irrevocable.” Around the country, both northerners and southerners seemed to be cooling down and accepting the results. In the South, organizers quietly canceled state secessionist conventions. The white southern electorate was obviously relieved not to have to consider armed resistance to the Wilmot Proviso, although that, of course, did not stop Democratic congressional candidates in Mississippi, Alabama, Georgia, and South Carolina from doing well that fall by running against the Compromise.48

Still, the questions provoked by the Mexican Wa r and northerners’ more persistent opposition to the expansion of slavery had not been solved, despite four years of devoting the entire political process to solving them. The newly confident North, angered by Texas and all the other issues that men like John Palfrey had branded with the label “Slave Power,” had stumbled upon the Wilmot Proviso as a line to draw, and then united behind it. The proviso promised to corral slavery, leaving it to decay, and end enslavers’ attempts to dominate the North and the nation. The slave South, battered by depression and demographic sluggishness, had seen a moment of great danger. It codified the mode by which it would defeat danger and then regain lost relative power: the federal government itself would be made to guard enslavers’ property rights, which were protected (southerners argued) by the Constitution, especially in new territories.

What hung on the political question of whether slavery would expand as a legally defined institution into new territories, first and foremost, were the futures of 3 million enslaved people. Neither side had succeeded in imposing its solution on them and on their futures. And both sides were still well-armed and primed, not only with adrenaline, but with literal powder. During one of the 1850 debates, Missouri Senator Thomas Hart Benton, an old Potterite brawler, bull-rushed Henry Foote as the Mississippian gave a speech. Foote pulled out a pistol, but fellow legislators dragged the two men apart. But loaded weapons were planted everywhere in the Compromise. One of its least-discussed but most important elements was the “organization” of the New Mexico and Utah territories. Taylor’s attempt to establish New Mexico as a free state had provoked southern outrage, so Clay suggested these territories be organized without protections for or restrictions on slavery. Most textbooks speak of the final outcome as if Clay’s proposal prevailed: New Mexico and Utah were to be testbeds for a demographic contest between slave and free-soil settlers. Yet while the committee that hammered out the New Mexico and Utah acts gave territorial legislatures power to legislate on slavery, proslavery and free-soil committee members cooperated to bake something else into the law. Their clause stated that if someone brought a lawsuit challenging the territory’s slavery laws—perchance a disgruntled enslaver whose property ownership was not protected by a territory that had enacted laws denying him the “right” to own slaves—the lawsuit would be fast-tracked straight to the Supreme Court. And then the Court would decide whether slave ownership and its expansion were protected by the Fifth Amendment, or the Fifth actually protected people’s ownership of themselves.49

Both sides in the debate thus gambled that their particular constitutional interpretation would prevail in the courts. Calhoun’s ghost would have placed his side’s bet with confidence. The Supreme Court had recently stated that the Constitution’s framers had insisted on protecting enslavers’ property outside of their home states. Now Congress, with the Fugitive Slave Act, had concurred. Due process of law might not, after all, permit the legislative emancipations that northern politicians like Palfrey believed would keep the Slave Power from capturing New Mexico. Moreover, a series of southern and southern-sympathizing Democrats had appointed the members of the Court. What would a reasonable person expect them to decide? And then, how would the increasingly confident North react? The New Mexico and Utah provisions of the Compromise of 1850 were in no way final. Instead, they built a platform for future rounds of conflict. Nor, as it turned out, was much else final about the Compromise.

ARMS

1850-1861

FOR THE REST OF his life, which was far longer and more successful than anyone would have predicted when he was a boy, Richard Slaughter insisted that this story was true. It starts with Richard and his cousin Ben on the James River, thirty miles upstream from the place where American slavery began. The year was about 1850; Ben was ten and Richard eight. In a Virginia devoted to raising cotton-pickers, not cotton, enslaved boys were a little older than their Alabama counterparts when they began their careers as full-time laborers. So that day they wandered, “catching tadpoles, minnows.” Down by the caved-in clay riverbank, Richard saw “a big moccasin snake,” a poisonous cottonmouth, “hanging in a sumac bush just a-swinging his head back and forth.” Like generations of other southern boys, Richard and Ben loved to hunt snakes, so they began to beat it with sticks. It opened its mouth as if to strike, but instead, “a catfish as long as my arm jumped out, just a-flopping.” “The catfish had a big belly too,” so they pounded on the fish. “He opened his mouth and out come one of those women’s snapper pocketbooks,” clenched like a slavemaster’s heart. They twisted open the snap. “Guess what in it? Tw o big copper pennies.” “Now you mayn’t believe it,” said Slaughter to his interviewer, eighty years later, “but it’s true.”

Only Richard and Ben were there. But the most important question about a miracle isn’t whether it happened, but what it meant. For without meaning a miracle is just a convenient accident. Richard and Ben had surely heard, in a Virginia Baptist church, the Gospel of Matthew, chapter 17. That fish story has a meaning. It begins with Jesus’s disciples asking if they should pay taxes to the Romans. The children of God don’t have to pay taxes, Jesus responds, “but so that we may not cause offence, go to the lake and throw out your line. Take the first fish you catch; open its mouth, and you will find a four-drachma coin. Take it and give it to them for my tax and yours.”

One way to interpret Matthew’s text is to read it as instruction on how to live as a saint in a world of sinners. There’s another interpretation. In this one, the fish is itself the parable, a sign that tells disciples that God will provide what they need, even enough to survive an oppressive regime. Grace will come in prosaic ways, like the ways that working men catch fish, or the way that two boys kill a snake.1

But fish swim in dark waters. Down there hide monsters. Eighteen centuries had rolled after Matthew was written by the time Richard and Ben’s ancestors crossed the waters. Spit out on the Virginia shore, sticky and gasping from the slave-ship’s belly, somehow they survived. To them were born children. To their children were born children. Until at last this day another beast came from the deep for their great-great-grandchildren. And its purse held a fortune as forked as the serpent’s tongue.

“I gave my cousin one and I took one,” Richard remembered. Richard’s penny grew lucky and luckier still as the years ran, as if its grace kept the serpent from swallowing him. As the domestic slave trade reached a new peak in the 1850s, he grew to adulthood unsold. One day, he looked down to the same river’s edge to see boats full of blue-clad men. They marched up to Richard Eppes’s big house, and on that day Slaughter claimed his freedom. Soon he put on his own blue uniform. For two years he carried a musket in the US Army, fighting battles, bringing freedom to his people. Afterward he made his own, richer life, learning to read and write, traveling the world, eventually returning to Virginia and settling into a routine as a fisherman who plied the same waters beside which he had once played.2

Richard reclaimed the parable. But Ben had drawn the other penny. Eppes “never sold but one man, that I can remember,” Richard told his interviewer. “That was my cousin Ben. Sold him South.” Ben carried his unlucky coin to Richmond. A third generation of dealers in young humans now worked from Bacon Tait’s old jail in Shockoe Bottom, where another round of innovations was under way. There, an enslaver could send instructions like these, which were received by slave broker Richard Dickinson: “If you have not sold Charles, try and get him to talk higher,” and that meant getting him to say the kinds of things that made him seem earnest and hardworking. “Probably you will have to get him whipped a few times before he will do.” Take out an insurance policy in the meantime—an economic innovation that, like the slave broker’s business of holding and selling without owning, reduced risk. So Ben played his role, too, talking high and higher as another sellable product of old Virginia. A few days later he was sweating in a boxcar, rolling toward the cotton belt. The South had missed out on railroad-building in the 1840s. The North surged ahead, and the slave states wallowed. But now the South was back on track, laying rails faster than the northeastern states during the 1850s. Iron roads and horses carried bales, planters, and hands, all at a far higher speed than Charles Ball’s raw feet walked the coffle-machine’s brass locks south to Congaree.3

They sold Ben in Alabama. As his years mounted, his reach grew longer, and the pounds he put up on the slate climbed higher. When weighing-up ended, he crept back to his cabin, pulled a soft, furtive cloth from between the logs, unwrapped the hidden penny. Lying down in darkness, he rubbed the copper, praying as it hummed with connection to the far-off state of his birth. Outside, through the starlit woods, in the dark cut where the railroad ran, extruded copper newly strung from pole to pole was talking circles around him. The telegraph hauled instant news of politicians’ fights over slavery’s expansion, descriptions running faster than the fugitives they named, price quotes for cotton pounds, purchase-orders for twelve-year-old boys.

For seventy years so far of slavery’s second life in the United States, the people who raised Ben and Richard had wrestled with the snake. They struggled each in their way with the evil that confronted them. Some ran. Some gave up. Some died. And some died and were yet reborn in new friendships, new marriages; new God, new self. But in the 1850s slavery’s expansion revived, too. Another 250,000 were on the slave trail to the southwest.

Over the years since Abraham Lincoln’s election in 1860, which prompted the secession of cotton states that led to the Civil Wa r and emancipation, authors have unleashed floods of ink attempting to explain white southerners’ actions. The authors already know how the story ends: with the blue-coated soldiers, Abraham Lincoln, and Richard Slaughter winning. Often, borrowing from the economic analysis of 1840s critics such as Joshua Leavitt, they assume that the South was a premodern economic system, and therefore that its defeat was inevitable—both on the field of economic competition, and on that of war. To cite again the words of the white abolitionist and orator Wendell Phillips, the South was a Troy destined to fall. Which then raises the question: What sort of madness would prompt supposedly conservative planters to start a war that would hasten the collapse of their own walls? Perhaps even more puzzling, what led the three-quarters of the white southern population who didn’t own slaves to fight, and hundreds of thousands to die, for such doomed madness?

From the 1780s onward, enslavers, along with other white southerners who supported them with votes and participated in the coercion of enslaved people, had consistently pressed to expand slavery’s territory. Lifetimes of experience had taught all of these white people to associate slavery’s expansion with its prosperity, with the growth of their own wealth and power, and even of their own pleasure. The Compromise of 1850 did not clearly permit future expansion, so enslaver-politicians spent the 1850s trying relentlessly to advance their agenda, even though many Americans had celebrated the Compromise because they were told it offered a “final” end to argument about precisely that issue. Such leaders were trying to implement a strategy that Calhoun and others had initiated in the previous decade: that of using political capital in the Democratic Party, the institutional power of the federal government, the threat of disunion, and constitutional argument to force the rest of the United States to acknowledge a southern “right” to expand slavery as far as enslavers wanted it to go. Their goals were evolving, but over the course of the 1850s, enslavers concluded that they wanted to see slavery expansion written into the laws of the nation and the covenants of its political parties, enforced in the territories by executive policy, and stated as constitutional fact by the Supreme Court. They convinced themselves that anything less meant that their future in the Union would not be secure.

For so long as active antislavery opposition could possibly shape government policies in the future, nothing could reassure anxious entrepreneurs that expansion could continue forever. This was despite a rupture between idealist older white abolitionists, who wanted to keep the antislavery movement untainted by party politics, and increasingly independent and pragmatic African-American abolitionists such as Frederick Douglass, who sought to inject antislavery ideas into northern party politics. Indeed, during the 1850s, Douglass and others who saw an opening in the political party system that had bound national interests to the expansion of slavery were proved correct. A growing number of white northerners heard stories carried by cotton-frontier refugees, or remained angry about post-1837 frauds and repudiations, or reacted to the enforcement of the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850. Whatever the reason, they left the collapsing Whig coalition. As an electoral vehicle, the new political formation they created—the Republican Party—could contain most of the enslavers’ free-state opponents, at least for a while. And northern economic and demographic growth had now made it possible that such an anti-southern party could, in theory, lose every southern vote and yet win national elections.

But enslavers did not see their own system as something antique, destined to fall before the onrushing future. Instead, they saw themselves as modern people who were running a highly successful, innovative sector of a world economy that was growing faster than ever before. For all the while, through all of the nagging political conflicts of the decade of the 1850s, slavery’s productivity kept expanding. Demand for their products stayed high in the longest sustained cotton-price boom of the pre-Civil Wa r era. Slavery’s entrepreneurs kept making more money. The only question was, Which fork in the road would the South choose, the one that kept it in the United States by securing a deeper national commitment to the expansion of slavery, or the one in which the region as a whole seceded in order to gain control of expansion for themselves?

Thus, from the vantage point of a post-1865 world, after the day when Richard Slaughter put on the blue uniform and shouldered a gun, after the day when survivors danced in Danville, it can be hard to see how the world looked before the cotton states seceded. But from the perspective of the 1850s cotton field, the account book, the train full of slaves, and the dark cabin where Ben clutched the unlucky penny, the future looked like one long rising serpent-curve of expansion. For the snake by the river ate parables. And all decade long, it never got full. Never once did Richard see his beloved cousin again. Yes, as they had always done in the selling states, they continued marrying and being given in marriage, being born, giving birth. But mothers disappeared faster than ever. Others raised the babies, and then the babies vanished, too. In those days, Lulu Wilson, along with her mother and siblings, lived in a Kentucky cabin. First the white folks disappeared Lulu’s father down the river on a steamboat. As cotton prices stayed high down at the bottom of the map, the older siblings trickled down, too. Clever, clever owner. He showed the merchandise, negotiated the deal, shipped the child off with the trader—all in one workday. Every time, Lulu’s mother got home from the field to find it was already over. “Oh Lord,” she screamed, falling on the cabin’s dirt floor, begging on her knees by the empty bed, “let me see the end of it before I die.”4

Lulu never forgot the scream, or the fear that the end of the begging and losing would never come. Her mother had little power, as an individual, to achieve freedom. She had less still to save her children. Under the new Fugitive Slave Act passed as an element of the Compromise of 1850, white people and their federal government were now obligated to pursue runaways from one end of the country to another. Collective revolt against slavery also seemed long since foreclosed by patrols, militias, armories full of powder and ball that ensured that any future Nat Turner was like a bug waiting for the hammer. And the rebels would wait alone. Relentless rhetoric had convinced almost all white Americans that African-American rebellion was unacceptable. Sure, white critics of slavery depicted slavery’s immorality, and sneered at the allegedly backward economy that slavery produced. They may have felt better. But they had no endgame to offer.

Maybe Frederick Law Olmsted, who during the Civil War would run the American Sanitary Commission—a quasi-governmental agency that tried to ameliorate the squalid living conditions endured by federal soldiers—thought he was the slaves’ ally. Yet he was just another Yankee tourist in the South. As he traveled from Virginia to Texas in the 1850s, gathering material for a book, thousands of other northerners roamed the South: railroad mechanics, cotton brokers, women on their way to marry planters’ sons whom they had met in New York. Most of them managed to get along fine, especially if their services added to southern whites’ balance sheets.5

Along the trails of Mississippi’s northern delta, poor northern men back-packed factory goods— ribbon, thread, locks—into a wilderness of cotton too new for stores. Rich men weren’t interested and shooed the tramping Yankees away from the big houses. The peddlers passed a field where a hundred people (heads down) picked like machines. Dripping, the travelers sat down on their packs, in the treeline at the end of a row. The peddlers “were treated badly by the rich planters,” remembered Louis Hughes, and “hated them, and talked to the slaves.... ‘Ah! You will be free someday.’” But the white-haired ones looked up from their sacks, saying, “ We don’t b’lieve dat; my grandfather said we was to be free, but we aint free yet.” Far across the field, the slumped overseer lurched awake in his saddle. The peddlers shrugged their packs up onto their shoulders and were gone.6

Olmsted could hardly have hidden the way his ears pricked up every time a companion at the steamboat rail or the men in the train seat behind him brought up the subject of slavery. He primed himself to find evidence that slavery was inefficient. So when he saw twenty-two enslaved men on a New Orleans street who had just been bought by an enslaver, it made him think, but not simply about the remarkable fact that some southern white men could borrow $20,000 and drop it on one gang of “hands” who would make cotton faster than any forty free men. He believed that a society laid down on a foundation of slavery had a limited capacity for expansion. So, “Louisiana or Texas,” he thought, counting the fingers of his mind’s right hand, “pays Virginia twenty odd thousand dollars for that lot of bone and muscle,” but beyond the levee a steamboat of German immigrants was chugging up the river toward Iowa. These free laborers, who cost nothing to import, built a society diverse in its production and consumption, laced together by “mills and bridges, and schoolhouses, and miles of railroad,” because they had incentive to work, to save, and to rise. The only thing left behind those twenty-two enslaved Virginians—when, after twenty years of mining Texas soil for cotton, their enslavers marched them west and south again to some new frontier—would be decaying cabins, divided families, and tangled debit accounts.7

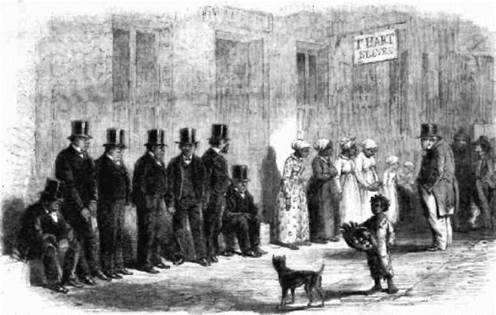

Image 10.1. Slave traders in New Orleans continued to receive and sell enslaved people whom they “packaged” as commodity “hands” in various ways—including by making them wear identical clothes. Illustrated London News, January—June 1861, vol. 38, p. 307.

Olmsted wrote four volumes about his journeys, relentlessly hammering home the argument that slavery’s inefficiency retarded southern growth and national development. During the preceding decade, as slaveholders’ collective finances collapsed, educated northerners had concluded that this belief was a fundamental truth. Former Illinois congressman and lawyer Abraham Lincoln insisted that only “free labor gives hope to all, and energy, and progress, and openness of condition.” Lincoln himself had escaped unpaid toil in his father’s muddy Indiana cornfields by walking to an Illinois frontier town, where he could work for a wage. On the way down to New Orleans, piloting his employer’s flatboats, he watched slaves toiling in the fields behind the delta levees. Returning to Illinois, he read law books, stood for elections, and turned himself into someone who hired other people.8

Even though slavery supposedly undermined the will to improve, northerners like Olmsted continually found southern whites pushing for efficiency. “Time’s money, time’s money!” he heard a white man say on a Gulf steamboat. Pacing anxiously as enslaved and free Irish longshoremen loaded his cotton bales, the man worried about getting back to Texas in time for planting. The rush of the annual cotton cycle predisposed such men to feel tardy, to push themselves to work harder at pushing other people harder. Yet maybe too much time had been lost in the 1840s, or maybe northern critics were right when they claimed that slaveholders had turned away from the path of progress, down some dead-end of history. Olmsted heard those questions lurking in conversations over dinner on steamboats. Southern whites raised such worries in a printed conversation that filled newspapers and monthly journals, such as DeBow’s Review, published in New Orleans by James DeBow. 9

Ultimately, however, despite something of a northern consensus that slavery was backward and inefficient, and despite the hard times of the previous decade, plenty of southern readers and talkers answered the question of whether or not the South could continue to use slavery as its recipe for modern economic development with a resounding yes. Take Josiah Nott, an Alabama racial theorist and a physician, who argued that mosquitoes, not swampy mists, transmitted malaria and yellow fever. In 1851, he wrote that “7,000,000 people” in the North, Britain, and France, “depend for their existence upon keeping employed the 3,000,000 negroes in the Southern states.” Emancipation would be in such circumstances “the most stupendous example of human folly.” A “network of cotton” wove enslaved people into the web of “human progress,” and without their forced labor, it would unravel.10

Over the decade, in fact, the ability of hands to undercut free and serf labor with ruthless efficiency reconfirmed the idea that whether or not Nott was right, Olmsted was wrong. In the hands of cotton entrepreneurs, slavery was a highly efficient way to produce economic growth, both for white southerners and for others outside the region. In the 1850s, southern production of cotton doubled from 2 million to 4 million bales, with no sign of either slowing down or of quenching the industrial West’s thirst for raw materials. The world’s consumption of cotton grew from 1.5 billion to 2.5 billion pounds, and at the end of the decade the hands of US fields were still picking two-thirds of all of it, and almost all of that which went to Western Europe’s factories. By 1860, the eight wealthiest states in the United States, ranked by wealth per white person, were South Carolina, Mississippi, Louisiana, Georgia, Connecticut, Alabama, Florida, and Texas—seven states created by cotton’s march west and south, plus one that, as the most industrialized state in the Union, profited disproportionately from the gearing of northern factory equipment to the southwestern whipping-machine.11

Although the whipping-machine could be astonishingly good at extracting productivity increases, some southern enslavers worried that dependence on world demand for cotton left the South vulnerable to two dangers: first, to the global economy’s vagaries, and second, to a future in which the northern states’ immigration-driven population growth steadily sapped southern political power. Regional newspapers and magazines regularly featured articles arguing that the South should create a diversified economy that included a profitable factory sector, which could provide jobs that would attract white labor to the South. In an 1855 issue of DeBow’s Review, for instance, William Gregg described his Graniteville, South Carolina, manufacturing complex, which he claimed was earning a profit of more than 11 percent. Others insisted that mining, iron-forging, and factory work could employ enslaved black labor. In quantitative terms, slave labor in southern factories produced as high a rate of net profit as slave labor in the fields. It was also as productive as free labor in the Northeast. Slaves staffed most of the expanding iron foundries of Virginia. From the 1830s onward, industrial activity had increased significantly in the South, and enslaved labor was one reason why.12

Industrially produced iron railroad tracks were redrawing the cotton frontier’s landscape. In the 1840s, southern railroads had expanded from 683 miles in total length to 2,162 miles. But this increase was much lower than that in the free states, which in the same time period created a 7,000-mile network concentrated in the Northeast and Middle Atlantic states. During the 1850s, good times returned, and southern railroad construction projects increased the regional network there to 10,000 miles in length. Corners of Alabama and Georgia, interior Florida, and East Texas had been too many days of wagon-hauling away from steamboat landings to become profitable cotton belts. But the railroads snaking up into hill counties made areas dominated by yeomen and poor whites ripe for transformation. Land speculation companies began to evict squatters. As total southern wealth increased, a new generation of poor whites found themselves turned into unwanted drifters, despised and feared by planters moving into the new railroad-opened regions. When Olmsted visited Columbus, Georgia, men told him that the local textile factory’s 20,000 cotton spindles were tended by displaced “cracker girls,” whose jobs supposedly saved them from the temptations of prostitution. Southern factories would occupy whites newly forced into landlessness, ameliorating the disruptive impact of the modern market on the Jeffersonian ideal of the independent small farmer as the backbone of the white republic.13

Дата добавления: 2015-09-04; просмотров: 62 | Нарушение авторских прав

| <== предыдущая страница | | | следующая страница ==> |

| TONGUES 17 страница | | | TONGUES 19 страница |