|

Читайте также: |

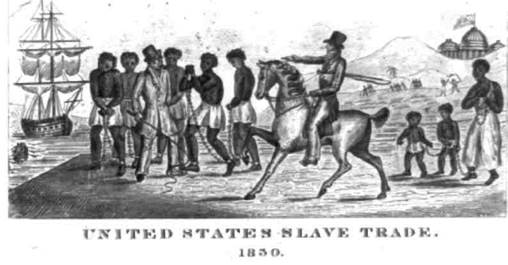

Image 6.2. In the 1820s and early 1830s, the domestic slave trade from the Chesapeake and Carolinas expanded rapidly. Formerly enslaved people and white observers alike noted the upsurge in activity. This was one of the first graphical representations of both the domestic slave trade and the pervasive family separations it caused. Print c. 1830. Library of Congress.

The new slave trade enabled eastern slaveholders to cash in potential wealth on distant markets. Some used the new trade to measure out their slave forces by the spoonful to the speculators, which allowed indebted planters to hold off creditors and stay in the Southeast. Other enslavers sold a few slaves to finance their own resettlement, or to set up one or more family members in the southwestern cotton-growing areas with young slaves so as to make a fortune that would save the old family establishment. “I have been disappointed in getting the negroes I expected of Mrs. Banister,” wrote S. C. Archer, who was trying to get in on the slave-trade business. “She intends sending her son Robert out [to Mississippi] as soon as he is old enough to manage all of her negroes for her.”14

Individual entrepreneurs penetrated different states in different ways and to different degrees. In South Carolina, collectively they produced a highly centralized output to interstate trade, in which most slaves destined for the New Orleans market were sold in Charleston. Judging from their height —65.3 inches, on average, for adult males, 3 inches shorter than southern white men—most of the South Carolina slaves who were sold came from the underfed and malarial rice plantations of the low country (see Table 6.3). But that didn’t stop Leon Chabert of New Orleans, the trader responsible for a large percentage of South Carolina purchases, from basing his business on them.

North Carolina, in contrast, was a terrain of vast rural stretches and little infrastructure. Its slave trade focused on a few towns, such as Salisbury in Rowan County in the western Piedmont. And here a series of men dominated the buying and transporting of slaves from the surrounding catchment area. In 1829–1830, it was James Huie. Within a few years Huie was displaced by local sheriff Tyre Glen and his confederates R. J. Puryear and Isaac Jarratt. Craven County, on the coastal sound, was the nexus of another significant trade, a concentration point for slaves brought in by sellers from outlying districts. A third major point was Chowan County in the northeastern swamps, where the county seat was the port town of Edenton.15

In Virginia the slave market was even more widespread. In 1829–1831, forty-one of the state’s counties sent at least fifteen people to Louisiana for sale. The whole state was, in the words of a former slave, “a regular slave market.” Professional slave-buyers traveled up and down every road and canal, peering into every courthouse town. Slave-selling financed the remaking of the Old Dominion’s political economy: Francis Rives reinvested profits from his Alabama slave-trading journeys in a coal-dealing firm that eventually supplied early railroads and factories with fuel. Thus the market for human flesh funded a new economy that was to be less dependent on plantation-style production, although newly dug canals kept bringing boats from the foothills of the mountains to the slave market in Richmond.16

Well-supplied with tempting cash by profit-savvy southeastern banks, slave-buyers in the 1820s and onward disciplined sellers to bring in exactly the kind of people the southwestern market sought. For instance, when Jacob Bell sold twenty-year-old Lewis to slave trader John Maydwell on September 1, 1830, in Kent County, Maryland, Maydwell was getting Bell’s most valuable property. Perhaps Bell would’ve preferred to keep Lewis, his only adult male slave, to work for him in Kent County. But Lewis would yield Maydwell $500 in profit when he was resold in New Orleans two months later. And Lewis was typical of those whom the traders extracted from the old states’ enslavers. First, he was young: 84 percent of those bought in the Southeast for New Orleans between 1829 and 1831 were between the ages of eleven and twenty-four. Second, he was male, and third, he was sold alone. Two-thirds of those brought southwest to New Orleans were male, and most were sold solo, without family or spouses. Even among the women of childbearing age, 93 percent were sold without children. “One night I lay down on the straw mattress with my mammy, and the next morning I woke up and she was gone,” recalled one former slave, Viney Baker.17

TABLE 6.3. MEAN HEIGHTS OF ADULTS, BY STATE OF ORIGIN, FROM NEW ORLEANS SLAVE SALES, 1829–1831

| GROUPS OF STATES | mean height (inches) | NUMBER OF ADULTS | STANDARD DEVIATION | |

| VA, DC, MD, NC | F | 62.86 | 2.512 | |

| M | 66.82 | 1,537 | 2.728 | |

| Total | 66.01 | 1,934 | 3.124 | |

| SC | F | 63.40 | 2.082 | |

| M | 65.29 | 2.311 | ||

| Total | 64.88 | 2.386 | ||

| KY, TN, MO | F | 64.38 | 2.860 | |

| M | 68.35 | 3.052 | ||

| Total | 67.32 | 3.484 | ||

| AL, GA, MS, LA | F | 63.67 | 3.399 | |

| M | 67.18 | 2.817 | ||

| Total | 66.20 | 3.370 | ||

| Total | F | 63.22 | 2.671 | |

| M | 67.00 | 2,066 | 2.850 | |

| Total | 66.18 | 2,638 | 3.215 |

Source: Baptist Database, collected from Notarial Archives of New Orleans.

Austin Woolfolk’s corporate organization included systematic channels of communication and exchange, widespread advertising, consistent pricing, cash payments, and fixed locations. He and his relatives concentrated people at fixed points in preparation for making large-scale shipments. Moses Grandy saw a set of Woolfolk’s barges coming into Norfolk, Virginia, from the Eastern Shore. Or, rather, he heard the boats, “laden with cattle and coloured people,” easing into the slack water by the docks. “Cattle were lowing for their calves, and the men and women were crying for their husbands, wives, or children.” The Woolfolks also shipped slaves across the Chesapeake to Baltimore’s Inner Harbor. Employees there offloaded enslaved passengers by night and marched them east up Pratt Street through the heart of today’s downtown Baltimore. Their “dead, heavy footsteps” and “piteous cries” woke young Frederick Douglass, who was living there in his enslaver’s townhouse. When the chained gang reached the end of the street, it was driven through an underground passageway that led up and out into the courtyard of a private “jail” designed for the trade. No more warehouses, barns, and taverns. From the jail, the Woolfolks sent slaves out to New Orleans by the sea route in regular dispatches, often renting entire vessels that carried one hundred or more people at a time. The vertical integration of this multistate enterprise enabled Austin Woolfolk, who had started as a mere Georgia-man, to pile up so much wealth that he could now play the grand gentleman. When University of North Carolina professor Ethan Allen Andrews visited Woolfolk at his Pratt Street pen in the 1830s, neighbors told him not only that Austin was “a most mild and indulgent master,” but also that his cash payments and standard prices proved he was “an upright and scrupulously honest man.”18

In the old Southeast, white people bought and sold black people on exceptional days. “It was customary,” wrote ex-slave Allen Parker of the early nineteenth century, “for those having slaves to let, to take them to some prominent place, such as a point where two roads crossed, on the first day of the New Year.” Quarterly court days also generated holiday crowds sufficient for community auctions, while Sundays, when gentlemen traded horses and people in the yard outside of the church, were also typical sale days. The certificates from New Orleans reveal, however, that from the 1820s onward traders like Woolfolk were buying slaves not on a traditional calendar of rural time, but in countless individual transactions throughout a new business year. Of the 4,000-plus certificates from southeastern states in the Notarial Archives, 89 percent were created on weekdays—Monday through Friday, which constitute only 71 percent of the week. One reason: individual sales on individual days in “business” places (such as the bar of the Easton Hotel, where Austin’s brother, John, met sellers) eliminated a problem: the possibility of staged auction bids by locals who might collude with sellers to drive up the prices. Slave buying and selling was no longer extraordinary, but ordinary, something businessmen did on business days. For despite Austin Woolfolk’s paternalistic act, his business was separating spouses and orphaning children. He and the new slave traders transformed the selling of human beings in the southeastern United States into a modern retrovirus, an economic organism that respected no ties or traditions and rewired everything around itself so that capitalism’s enzymes of creation and destruction could flow unimpeded.19

At the same time, the new convenience of slave-selling also met sellers’ desires and needs. Soon enough, authors building on free-floating cultural excuses would publish plantation novels that painted Chesapeake enslavers as reluctant slave-sellers who were driven by debt or other forms of catastrophe to send family property to the market in order to raise money. But the pattern of sales does not suggest that enslavers were paternalistic planters who had fallen on hard times, and who were thus being forced to sell off slaves to make ends meet. Instead, they were men and women who were extracting cash from small portions of their total reserves of human wealth whenever they wanted it. More than half of the slaves in the South were owned by whites who claimed twenty or more people as their property. Two-thirds of the sales in the 1829–1831 records were executed by slave owners who sold no more than four slaves during this time span. If they had been hit by catastrophe, surely they would have sold more slaves all at once. “I am in want of money,” wrote B. S. King of Raleigh, North Carolina, in 1825, even as he mumbled about the moral repercussions of selling a man away from his wife. In the end, “I am in want of money” usually won. “You know every time they needed money they would sell a slave,” said Robert Falls. Traders calibrated their innovations not only for southwestern entrepreneurs who wanted hands, but also to provide a highly useful service to southeastern white folks—the ability to turn a person into cash at the shortest possible notice.20

THE DOCUMENTS CREATED IN William Boswell’s New Orleans notary office reveal another reason why the Missouri crisis was not even a blip on the long upward climb of slavery’s expansion, which in the 1820s saw the transfer of 150,000 enslaved people from the southeastern states to the southwestern states and territories and an increase in US cotton production from 350,000 four-hundred-pound bales in 1819 to more than 800,000 in 1830. The name with which Ellen’s seller acknowledged his receipt of Barthelemy Bonny’s $450 was a strange one, especially for a man who fished the seas of Kent County and its surroundings. Granville Sharp Pierce’s parents had chosen to name him after a different kind of disciple: the eighteenth-century Anglican priest Granville Sharp. That original Granville had been known for several things, including his research on the grammar of biblical Greek. But Sharp was most famous as an international abolitionist. In the early 1770s, James Somersett, an enslaved man born in Virginia, was brought by his enslaver to London. There he escaped and sought Granville Sharp’s help: the runaway wanted to sue for freedom in a London court. Somersett won the case. The decision ruled that slaves became free the moment they set foot on Great Britain itself, although slavery remained legal in the rest of Britain’s empire. Sharp next attempted to convince the British authorities to prosecute the captain of the slave ship Zong for ordering his crew to murder 122 Africans in the middle of the Atlantic when water supplies were running low. Sharp also helped to found the colony of Sierra Leone, where the Royal Navy (once the British government abolished British participation in the international slave trade in 1808) would land Africans recovered from captured slave ships.21

Granville Sharp was emblematic of an earlier generation of English-speaking antislavery activists. Their late eighteenth-century offensive targeted the first slavery, especially that of the sugar islands. That system depended, above all, on the Middle Passage, they charged, and they sought to limit slavery by ending the Atlantic trade. The American version of this long-gone antislavery movement had helped to emancipate slaves in marginal areas of the North. What these movements had in common was that they were composed of elite men who were trying to convince centralized power —Parliament, Congress, state legislatures elected by property-owning citizens—to mandate change through legislative or royal decree. Despite its elitism, Granville Sharp’s generation did shift the center of polite society’s opinion against the Middle Passage. By 1808, the governments of both the United States and Great Britain had outlawed their citizens’ participation in the international slave trade. Sharp and his allies had concentrated on the international slave trade because they believed that without the continual importation of new slaves from Africa, the sugar plantations of the Caribbean would die out.22

Yet even as northern states were freeing most of their last slaves in the 1820s, the claim that slavery harmed the American political economy looked less persuasive every day in light of cotton’s astonishing profits. The interstate slave trade mocked the hopes of the abolitionists that slavery would die on its own. And Granville Sharp’s generation had not been replaced. No substantive opposition to the expansion of slavery existed among white Americans. After the Missouri Compromise, active white opposition to slavery dwindled toward the vanishing point. Most of those who conceded that slavery was morally wrong in the abstract refused to do anything concrete about it. It was easy to blame Georgia-men for “excesses,” as all the while the speculator upgraded the Georgia-man. It was easy to propose the transportation of African Americans “back” to an Africa that they had never seen. It would never happen. John Quincy Adams, for instance, only needed to calculate on his fingers to see that hoping for an end to slavery through “colonization” was a “day-dream.” And all the while, every new hand in every new cotton field meant markets for northern produce, more foreign exchange, cheaper raw materials for northern industry, and more opportunities for young Vermonters and Pennsylvanians who moved to Natchez. Slavery’s defenders had won the arguments that mattered. Even a man whose parents had named him after Granville Sharp had become a speculator.23

In the 1820s, enslaved people on slavery’s frontier faced the yoked-together powers of the world economy, a high demand for their most crucial commodity, and the creatively destructive ruling class of a muscular young republic. And they faced it all alone. For many years, enslaved people could only push back with hushed breaths around ten thousand fires on the southwestern cotton plantations —or in the Southeast, among those left behind. Although they had to keep them from white ears, the words that made up their critique of slavery mattered tremendously to them and to the future. Around the fires, or late at night with a mouth pressed to the ear of the person with whom one shared a bed, or coded in the testimony of the faithful at all-black religious meetings, enslaved people said the word “stole,” and so described a history that undermined all of the implicit and explicit claims enslavers made to defend slavery. Among those with whom they now spoke a common tongue, they dared to disagree with the claim that slavery would expand, and that no one should do anything much to interfere. They rejected the claim that God, nature, or history had destined them for slavery. They exposed the assumption that white people’s needs ought to trump their own, or the idea that money ought to trump conscience, pitting this word of their own against every word written on papers like the ones Granville Sharp Pierce carried with him to William Boswell’s office.

“My mother and uncle Robert and Joe,” said Margaret Nickerson of Florida, “[they] was stole from Virginia and fetched here.” Lewis Brown explained his own genealogy in this way: “My mother was stole. The speculators stole her and they brought her to Kemper County, Mississippi, and sold her.” Over and over, enslaved people said that when they were sold, or otherwise forced to move, they had been “stolen.” In so telling their personal histories, they accomplished two things. First, they used a newly common tongue to make their own personal histories part of a larger story. And second, they made it clear that this common story was a crime story. Buying and selling people was a crime. Buyers and sellers were criminals.24

Critiques of slavery as theft had been made before. But the context was different now. The international slave trade was closed, and enslavers could pose as the architects of a “domesticated” system no longer sustained by wars of enslavement in Africa. Meanwhile, the New Orleans notarial records, like all the legal records of southern slavery, described the rupture that Granville Sharp Pierce imposed on Ellen’s life as a legitimate transaction in legally held property. Most whites, whether in the North or the South, believed that slave owners had obtained their slaves by orderly business transactions, well recorded in law. And as the economy changed, they were suggesting that owners of property should be able to do whatever they wanted with what they legally owned. In such a context, when enslaved people said to each other, “ We have been stolen,” they were preparing a radical assault on enslavers’ implicit and explicit claims to legitimacy, one that would lay an axe to the intellectual root of every white excuse—even ones that hadn’t yet been dreamed up. For describing slavery and its expansion as stealing meant that slavery was not merely an awkward inconsistency in the American republican experiment, or even a source of discourse about sectional difference. Slavery was not, then, merely something that pained white people to see. Instead, “stealing” says, slavery is a crime.

One word, “stole,” came to be a history—an interpretation of the past and how it shaped the present—from Maryland to South Carolina to Texas and everywhere in between. Enslaved people recognized that the slavery they were experiencing was shaped by the ability of whites to move African Americans’ bodies wherever they wanted. Forced migration created markets that allowed whites to extract profit from human beings. It brought about a kind of isolation that permitted enslavers to use torture to extract new kinds of labor. It led to disease, hunger, and other kinds of deadly privations. So as these vernacular historians tried to make sense of their own battered lives, the word “stole” became the core of a story that explained. It revealed that what feet had to undergo, and the way the violence of separation ripped hearts open and turned hands against body and soul, these were all ultimately produced by the way enslavers were able to use property claims in order to deploy people as commodities at the entrepreneurial edge of the modern world economy.

In this critique, slaveholders were not innocent heirs of history, which is what Jefferson had made them out to be. Instead, slavery’s expansion was consciously chosen, a crime with intent. Years after slavery ended, former slave Charles Grandy reflected on the motives of the enslavers who had shipped him from Virginia to New Orleans for sale. After a lifetime, he had made it back to Norfolk. Now he asked his interviewer, an African-American academic just like Claude Anderson of Hampton University, if the young man understood the significance of the statue of the Confederate soldier that loomed on a high pillar down by the harbor. Grandy himself had once passed the statue’s eventual site in the hold of a slave ship. “Know what it mean?” Grandy asked. But the question mark was rhetorical, he already had an answer ready: it meant, he told the interviewer, “Carry the nigger down south if you want to rule him.”25

The statue stood as a post-hoc justification for the same desires that had led whites to steal him from his Virginia life, or Hettie Mitchell’s mother from her Carolina parents. For if you want to rule a person, steal the person. Steal him from his people and steal him from his own right hand, from everything he has grown up knowing. Take her to a place where you can steal everything else from her: her future, her creativity, her womb. That was the true cause working behind the history of the nineteenth century, Grandy insisted, from slavery’s expansion to its political defense, and to the war that its proponents eventually started. Talk about “stealing” forces a focus on the slave trade, on the expansion of slavery, on the right hand in the market, on the left picking ever faster in the cotton fields. In this story there is no good master, no legitimate heir to the ownership of slave property, no kindly plantation owner, only the ability of the strong to take from others. Stealing can never be an orderly system undergirded by property rights, cushioned by family-like relationships. There is no balance between contradictory elements. There is only chaos and violence. So when enslaved people insisted that the slave trade was the crystalline form of slavery-as-theft, they ripped the veils off a modern and modernizing form of slavery, one that could not be stabilized or contained. Constant disruption, creation, and destruction once more: this was its nature.

“I heard this over again so many, many times before grandmother died,” said Helen Odom of her grandmother’s story about being taken to Arkansas and sold—“the greatest event in her life.” Talking with each other night after night about how slavery’s expansion had shaped their own lives, enslaved people, taken away or left behind, created a vernacular tradition of history that encouraged storytellers to bend every migration tale around the fulcrum of theft. And almost every tale fit. The standard methods used by slave traders were, indeed, much like kidnapping, just as the tales said. If you had been seized, tied to the saddle of a horse like a sack of meal, and ridden off without a chance to kiss your wife goodbye forever—this is what happened to William Grose of Virginia in the 1820s —you might compare your experience to that of being kidnapped.26

Some African Americans who toiled in the cotton and sugar fields had in fact been literally “stolen” even within the framework of whites’ property claims. John Brown watched slave trader Starling Finney and his men abduct a girl from her owner in South Carolina. The thieves kept her in the wagon on the way down to Georgia, partly so that they could repeatedly gang-rape her, but also to hide her from potential pursuit by the girl’s owner. Julia Blanks said that her grandmother was freeborn in Virginia or Maryland, but whites lured her into a coach in Washington, DC, drove her to the White House, and presented her as a gift to Andrew Jackson’s niece. Still other slaves, who had been expecting freedom under the gradual emancipation laws of northern states, found themselves in Louisiana or Mississippi when unscrupulous owners sold them south before their freedom came. Between 1825 and 1827, Joseph Watson, the mayor of Philadelphia, pursued at least twenty-five cases in which free African Americans from his border-state area had been abducted and taken to Mississippi and Alabama. Most were children. Watson hired lawyers in Mississippi, wrote letters to slave-state government officials, and tried to organize prosecution of the alleged kidnappers, to little avail.27

Sometimes enslaved people conflated kidnapping and plain old-fashioned slave dealing because, like Carey Davenport’s father, they were unsure of their actual legal status. Davenport’s father was supposedly promised freedom by his “old, old master” in Richmond. But after the old man’s death, his son “steal him into slavery again,” said Davenport. People who claimed to be kidnapped free men or women might have been looking for some sort of individual “out” from the shame of slave origins. Not I, someone like James Green might suggest, I did not belong in slavery, because I, as an individual, was kidnapped. His father, he said, was a “full-blooded Indian.” His mother’s owner, “Master Williams,” who “[called] me ‘free boy,’” walked “free” James down the street to the Petersburg, Virginia, auction block one day and had him sold to Texas. Green spoke as if it had all been a mistake. He never should have been subjected to slavery’s humiliations. But Green’s daughter called him on his self-deception. She “took exception,” remembered the interviewer who met them both, “to her father’s claim that he was half Indian.” She knew that her father’s lighter skin and ambiguous status (“I never had to do much work [in Virginia] for nobody but my mother”) revealed that “master Williams” had actually put his own son on the auction block.28

To the enslaved, only one other set of events in remembered history seemed as significant as the forced migration that was consuming their families and communities at an accelerating rate in the 1820s. Long after 1808, plenty of people in the South could still talk about how they had been stolen from Africa into the Middle Passage. In 1844, asked to give his age, an African-born Florida man replied, “Me no know, massa, Buckra man steal niggar year year ago.” To understand and explain the expansion of slavery in which they found themselves, American-born listeners borrowed terms from African survivors who had told them of how the first slavery had been made. “They always done tell it am wrong to lie and steal,” said Josephine Hubbard. “So why did the white folks steal my mammy and her mammy from Africa?” “They talks a heap ‘bout the niggers stealing,” said Shang Harris. “What was the first stealing done? It was in Afriky, when the white folks stole the niggers.”29

In the 1820s and 1830s, as the new professional slave trade in hands became institutionalized and expanded exponentially, so did the stories and so did the number of tellers. The themes of theft, the indictment of whites, and the understanding that the personal disruptions drove a new form of slavery all deepened. Anyone, enslaved people came to understand, could be taken and transported southwest. All of those taken were in some way stolen, for the basic rituals of this emerging, modern market society were absurd disguises for thievery. So, for instance, implied the apocryphal tale of a woman named Venus, whose story circulated around southern fires for decades. Shoved onto the auction block by her enslaver, Venus scowled down at those who eagerly bid on her. Then she interrupted the auctioneer’s patter with a sarcastic shout: “Weigh them cattle!” Such stories became classics, delivering again and again a powerful freight of indictment of whites, leading listeners from their own particular experiences into wider criticism of the absurdity of buying and selling human beings as property. “What was the law”—the one that should be, or even, in the case of children kidnapped from free states, the law that white people themselves had written—“what was the law, when bright shiny money was in sight?” asked Charley Barbour. “Money make the train go... and at that time I expect money make the ships go”—to New Orleans with slaves, to Britain with cotton. Instead of being individual misfortunes, enslaved people realized their own experiences were part of a giant historical robbery, a forced transfer of value that they saw every day in the form of widening clearings, cotton bales moving toward markets, and slave coffles heading further in.30

African Americans were not confused about what they thought of slavery’s expansion. Yet in the 1820s enslaved people’s vernacular history of being stolen was still hidden on the breath of captives. And these captives had been carried far away from any audience that had the political or economic power to do much about the situation of enslaved people, or about the endlessly multiplied theft that was still in progress. Forced migration taught enslaved people to call slavery stealing, and it provoked them to take extreme measures to escape. In 1826, an ad appeared in the Natchez Gazette offering $50 for anyone who could capture Jim, a slave who had escaped from owner William Barrow. Purchased from Austin Woolfolk late the preceding fall at New Orleans, Jim had now run away, and Barrow suspected he’d try to “pass for free” on steamboats. Jim had a speech impediment, Barrow’s ad pointed out. Geography also impeded escape. Most likely, Jim did not make it, although a few did. The same new technology that sped the passage of enslaved migrants up the rivers of the cotton country could also carry stowaways out.31

Дата добавления: 2015-09-04; просмотров: 185 | Нарушение авторских прав

| <== предыдущая страница | | | следующая страница ==> |

| TONGUES 3 страница | | | TONGUES 5 страница |