|

Читайте также: |

The group that joined Plumer in the capital during the early winter of 1819 was a new Congress, elected in 1818. In the thirteen months between the time of their election and the time of their seating —lame ducks lasted much longer in those days—a major financial crisis had erupted. The Panic of 1819 embroiled the administrators of the Second Bank of the United States in scandals that demanded legislative attention. But the debate over Missouri continued, too. Even though Kentucky representative and Speaker of the House Henry Clay was working behind the scenes with a middle group of congressmen from both free and slave states, trying to organize a compromise, tempers on the floor of the House grew more and more heated. Rumors whispered that congressmen were carrying pistols into debate.23

John Quincy Adams—a New Englander in a southern administration, trying to focus on his negotiations to acquire Florida from Spain—had assured an audience in the summer of 1819 that he believed the restriction of Missouri slavery was unconstitutional. But while negotiations dragged on into February 1820, and as Monroe used the power of the executive to lean on northern Republicans to break from the slavery-restriction ranks, Adams had a startling late-afternoon conversation with Secretary of Wa r John C. Calhoun, a South Carolinian. Calhoun predicted that the Missouri crisis “would not produce a dissolution” of the Union. “But if it should,” Calhoun continued, “the South would of necessity be compelled to form an alliance... with Great Britain.” “I said that would be returning to the colonial state,” replied the shocked Adams, who remembered two wars with the old empire. “He said, yes, pretty much, but it would be forced upon them.”

Adams fell silent. But in his diary, his pen wrote thoughts that his voice was afraid to breathe: “If the dissolution of the Union should result from the slave question, it is as obvious as anything... that it must be shortly afterward followed by the universal emancipation of the slaves.” For “slavery is the great and foul stain upon the North American Union.” The opportunity of war would mean that “the union might then be reorganized on the fundamental principle of emancipation. This object is vast in its compass, awful in its prospects, sublime and beautiful in its issue. A life devoted to it would be nobly spent or sacrificed.”24

Yet, just like Calhoun and all the other cabinet men, Adams was thinking not of self-sacrifice, but of the election of 1824, Monroe’s retirement, and his own possible candidacy for president. In public his tongue stayed silent on this issue—for now. And by early 1820 Clay could offer the House an already-passed Senate bill that admitted Missouri as a slave state, and added Maine (sectioned from the northern coastlands claimed by Massachusetts) as a free state, to keep the Senate balanced. The bill also barred any more slave states from being carved out of the Louisiana Purchase above 36°30' north latitude, essentially Missouri’s southern border. Southern senators thought this deal gave up little of practical importance. One could not grow cotton and sugar in the Dakotas. When free-state representatives in the House shot down the combined compromise bill, Clay divided it into separate Missouri statehood and restriction-line bills. Then southerners, plus a few northerners, voted for Missouri statehood (with slavery), while northerners passed the 36°30' restriction line. At last the crisis was over.25

With the Missouri statehood issue, the expansion of slavery had been presented as a stark choice, one uncomplicated, for instance, by the desire to bring Louisiana into the Union so that European empires could no longer block national expansion. Northern politicians had united almost instantaneously against it. The shock of this opposition helps explain, perhaps, why southern politicians reacted with their own startling level of emotion and threats of secession. Southern forces in Washington had relied on the Senate’s balance between free-state and slave-state delegates to accomplish further expansion—and those who took a calculating view understood that northern money, especially that represented by New Englanders (who had lagged behind the anti-expansion zealots), was unlikely to slap away the hand that fed it. Merchant elites who depended on the shipping trade still dominated New England politics. While some southerners might complain that a wall of Spanish territory to the west of Louisiana now blocked further expansion, the compromise dealmaker, Clay, thought he could add Spanish Texas to the Adams-Onis Treaty—which already ensured that enslavers would get Florida. He wasn’t able to do so, but southern leaders like President James Monroe still believed that Texas would inevitably fall to the United States. And many, both North and South, now thought that the Missouri Compromise—as it came to be known—had established a precedent of dividing the West between free and slave territory. They would come to refer to the Compromise as a “sacred compact.”26

The Missouri controversy caused many southern enslavers to become overly sensitive to future criticism; northern opposition to the expansion of slavery, however, dissipated when the crisis was over. Before 1819, there had been no such thing as an organized opposition to slavery or its expansion among northern whites. After 1821, northern whites returned to ignoring the rights of African Americans or the consequences of slavery and its expansion for the enslaved. The few northern whites who recognized that slavery raised important moral issues—issues that went beyond the question of whether it was a stain on the national honor—did not act, but rather cast off upon Georgia-men or other bad actors the moral weight of slavery’s expansion. Moral discomfort and political interest did not coalesce into a lasting opposition to expansion. Indeed, by 1821, some southern leaders were realizing that they would have little trouble creating winning interregional coalitions that allowed for further exploitation of enslaved African Americans so long as they could make a claim that their policies supported increased democracy among whites. Northerners were doing their best to give that impression, at any rate. For instance, even as the ink dried on the Missouri bills, New York was holding a state constitutional convention. In the new document they created, delegates who wanted to undermine the power of the state’s traditional elites eliminated property requirements for white men who wanted to vote, but increased the barriers for black men.

BY THE EARLY 1820s, it was simply the case in the United States that enslaved people could look to no one but themselves for help. And yet they were outnumbered and outgunned, so rebellion and direct resistance would lead only to certain defeat. They would have to change their world in different ways, but even building from within presented problems. Forced migration, which atomized groups and erased identities, required enslaved migrants to create new ties to each other in the constantly changing places where they found themselves. That would not be easy. But people, and indeed the world, can change from things as invisible and acts as ephemeral as words on the wind.

One Thursday evening in October, sometime around 1820, a Kentucky enslaver named Taylor waited on his porch. Between his barn and his house waited a huge pile of corn in the husk, which needed to be prepared for storage in his barn. Soon he heard muffled sounds: groups of enslaved men and women converging through the woods from their owners’ property, singing as they came to shuck his corn.

In one of those columns was Francis Fedric, who in 1863 recorded what happened on that night four decades before. And at the head of his line strutted the night’s star, a tall, quick-witted young man named Reuben. Reuben’s cap bristled with sticks and feathers, decorations for the chosen champion of friends and cabin-mates who planned to test their skill and heart in a competition to see which gang could shuck Taylor’s corn most swiftly. Soon, scores of men poured into the fire-lit circle where the corn lay heaped, while women moved around the edges to form an audience. The men who knew each other traded jokes and gave sizing-up glances to new ones. Reuben and another captain huddled to decide the ground rules. Then the selected pair chose up sides, who divided the corn pile in two. Taylor handed each captain the all-important jug of liquor.27

With a rush the men dived in, grabbing ears and pulling off the shucks, while each captain leapt to the top of the pile, and, turning to his team, took center stage. His job was to lead and encourage his team by making up humorous, catchy verses that the team would then repeat or answer even as they in ceaseless motion pulled off shucks, tossed the naked ears into the “clean” pile, and passed the jug. In corn-shucking competitions, captains sung out rhymes that ridiculed other enslaved people, present or absent, by name or by implication: “Dark cloud arising like [it] going to rain / Nothing but a black gal coming down the lane.” Which dark-skinned woman steamed up with anger or sneered with contempt at these sour grapes? Other lyrics took different risks, slyly chanting half-praise of an owner. Still others talked politics in ways palatable to some owners but rankling to partisans of the other side: “Polk and Clay went to war / Polk came back with a broken jaw.” Some even criticized, for those who had ears to hear—“The speculator bought my wife and child”—this was a slow dragged-out verse—“And carried her clear away.” Or they demanded more of the liquor that fueled the long-night labor of shucking—“Boss man, boss man, please gimme my time; Boss man, boss man, for I’m most broke down.”28

They worked on past midnight. Whiskey flickered in their bellies and laughter roared, keeping them warm despite the chilly fall air. The smell of the ox roasting a few dozen yards away urged on the rings of grabbing, tearing men. The piles shrank. The captains’ hoarse voices sped the rhythm. At two in the morning, Reuben’s band frenetically, triumphantly shucked their last ears and rushed to surround the others’ sweating circle, waving their hats and singing to the defeated, “Oh, oh! fie! for shame!” But the shame did not sting for long, for now, behind Reuben, they all marched down to Taylor’s house. He waited there on the porch with his wife and daughter. The enslaved men crowded around it and sang one last time to Reuben’s lead: “I’ve just come to let you know / [Men] Oh, oh, oh! / [Captain] The upper end has beat / [Men] Oh, oh, oh! /... [Captain] I’ll bid you, fare you well / [Men] Oh, oh, oh! / [Captain] For I’m going back again / [Men] Oh, oh, oh!” Then they all went back together to shuck the last ears in the losing team’s pile, after which all the corn-shuckers sat down at long tables to feast.29

The fun and local fame that enslaved people won at such occasions were as fleeting as the meal. Tw o weeks later, thirty of the men who shucked corn at Taylor’s on that night were sold to buyers who were now, in the late 1810s, beginning to comb Kentucky every December. Reuben was among the first “dragged from his family,” recalled Fedric: “My heart is full when I think of his sad lot.” Yet even as raw memories of his own sale from Virginia flooded his thoughts, Fedric could not forget Reuben’s night of triumph, the way he had led more than one hundred men with virtuosity of wit and artistry of tongue. For that night those three hundred men had all ridden on his gift despite everything that hung over them. And Reuben had soared highest of all.30

Here is something that is no accident: the most popular and creative genres of music in the history of the modern world emerged from the corners of the United States where enslavers’ power battered enslaved African Americans over and over again. In the place Reuben was being dragged to, and in all the places where forced migration’s effects were most dramatic and persistent, music could not prevent a whipping or feed a single hungry mouth. But it did serve the enslaved as another tongue, one that spoke what the first one often could not. Music permitted a different self to breathe, even as rhythm and melody made lines on which the common occasions of a social life could tether like beads. Times like corn-shuckings, when people sang and played and danced, became opportunities for people to meet. There they mourned, redeemed, and resurrected sides of the personality that had been devastated by forced migration.

On such occasions—and perhaps even more so on Saturday nights when whites weren’t watching —people animated by music and by each other thought and acted and rediscovered themselves as truly alive, as people who mattered for their unique abilities and contributions, as people in a common situation who could celebrate their own individuality together. Back in Maryland, Josiah Henson’s father had played a banjo made from a gourd, wood, and string. This African instrument, Henson remembered, was “the life of the farm, and all night long at a merry-making would he play on it while the other negroes danced.” But around 1800, Josiah’s father ran afoul of his owner, who had the man’s ear severed in punishment. Deformed and angry, the maimed man let his banjo fall silent. Soon the owner sold him south, far away from Josiah. “What was his after fate neither my mother nor I ever learned,” Henson wrote decades later. But any southwestward course was likely to drain a man down into the great trap of New Orleans.

Image 5.1. Corn-husking: an opportunity for community-building, mutual recognition, and improvisational freestyle battling that showcased individual virtuosity. Harper’s Weekly, April 13, 1861, p. 232.

In 1819, as white people began to shout and threaten each other over Missouri, a visitor wandered on a Sunday to the open space on the northern border of the French Quarter. Today the maps call this place Louis Armstrong Park. The visitor had already heard it referred to as Congo

Square. He saw men drumming in a circle while a wizened elder played a banjo. Two women danced in the middle while “squall[ing] out a burthen to the playing, at intervals.” In the 1830s, William Wells Brown, then an enslaved employee of a slave trader, found Congo Square still thundering with African drumming. In each corner, a different African nation—the Minas, the Fulas, the Congos— played their own music and danced their own dances while others watched, nodded heads, and jumped in. Drums sped and slowed, talking in rhythms brought thirty years before from beyond the salt water. Dancers wove patterns that talked, too. If Henson’s father had come there, he might have realized that he and they sang in the same family language.31

So perhaps he would have picked up his banjo again. Long-lost relatives had much to teach him and others from the Chesapeake and Carolinas, where the drum had long been outlawed. And southeastern migrants had much to teach immigrants from Africa or the Caribbean. The surging patterns of sawing fiddle and plunging banjo, and the stripped-down, charging syncopation of their music, were innovations produced over the course of two hundred hard years in the New World. Southeastern migrants’ own personal experiences of exile and movement within the country spread and then transformed their performance styles again. One 1800s writer claimed that “the Virginian negro character therefore has come to prevail throughout the slave states,” and that “every where you may hear much the same songs and tunes, and see much the same dances.” Virginia’s exiles now sang about what made them no longer Virginians. Their songs evoked the traumas of separation in a modernizing society in musical ways more complex than words alone could achieve.32

“Traveling through the South,” wrote an early white commentator on nineteenth-century African-American music, “you may, in passing from Virginia to Louisiana, hear the same tune a hundred times, but seldom the same words. This necessarily results... from the habit of extemporizing, in which the performers indulge on festive occasions.” Only one thing about these performances was fixed: that they were not to be fixed. Instead they mixed together even well-known components of rhythm, melody, lyrics, and motion in fresh ways. So, for instance, from 8 p.m. until 2 a.m., Reuben had kept his footing on the pile of corn because he had trained for it; he had gained, under the tutelage of peers and elders, the ability to sing a song that he continually made up, and revised, and created all over again.33

In the nineteenth century, white European and American authors began to claim that they had become uniquely individualistic, modern, not bound to repeat the old. And the modern Western world did seem to be celebrating the individual. Think of Walt Whitman, singing a song not about the greatness of the tradition he’d been handed, but of himself. By the time Reuben sat chained to the deck of the slave-trader’s flatboat on his way from Kentucky to Louisiana, every state he floated past had opened up voting to almost every individual white man. Hence Whitman’s song to himself, and the celebration of the self and of American individualism, which would be emphasized over the coming century in white art forms. When white people wrote about black culture in the nineteenth century, however—and often when they have written since—they placed African-American art forms with the traditional cultures of the premodern world, which supposedly did not have a concept of the autonomous self. White people’s accounts depicted black dancers and singers as acting on tradition, or even instinct, rather than attributing individual genius to them—and these accounts served as just-so stories that had the added benefit of implicitly justifying slavery. Whites explained their own attraction to enslaved people’s music by crediting African Americans with unusual “powers of imitation,” the primitive ability to forget the self in bacchanalian revels. By the late nineteenth century, whites believed, as many still do, such quasi-biological myths—that African-descended peoples had a “natural,” biologically innate, unchanging, common response to rhythm.34

But it was enslaved African Americans who were the true modernists, the real geniuses. The innovation that flooded through the quarters of frontier labor camps in the first forty or fifty years of the nineteenth century was driven by constant individual creativity in the quarters’ tongues. In the real world in which people like Reuben were trying to survive, individual creativity improved an enslaved African American’s chance of survival, and not just by enabling him or her to find a faster way to pick a pound of protection from the whip. Skillful words made one valuable to self and peers; they helped the enslaved to see themselves not as hands but as voices. And being a voice recognized by one’s peers gave one a reason to live. So no wonder music and dancing on slavery’s frontier emphasized individual improvisation, not imitation, and not unison. No wonder that at corn-shuckings, at log-rollings, and at every Saturday night party, people swept from every mooring by slavery’s westward-rolling tsunami sought moments like the ones that seared the memory of Reuben into the folds of Francis Fedric’s brain. They strove to loose their tongues from fear and anxiety, so that they could do something that marked them as unique, their words and steps as novel, themselves as worthy of their peers’ respect. There always came a space in the gathering and a moment in the song where, like Reuben, the individual performer did his or her unique thing. And then the performer’s peers reveled in his or her triumph, while “all the peoples,” said Hattie Ann Nettles, “cut the high step,” young and old, man and woman.

For not everyone was a virtuoso, but in contrast to the vast majority of whites, no one was a specialist non-performer. Everyone could sing and dance in the circle. Anyone willing to try could jump in the middle of a ring. Women and men both took the center. As was the case wherever African Americans gathered together in the young United States, not even the men expected the women to be modest and retiring. “You jumped and I jumped / Swear by God you outjumped me!” sang out the man at the corn-shucking. The workers, laughing with a man laughing at himself, sang back “Huh! Huh! Round the corn Sally!” Sally was a name from a song, but maybe Sally’s stand-in danced while the men recognized that her boldness might outjump that of her husband or lover. Other women earned the reputation of the “fastest gal on the bayou” by “dancing down” one man after another in the center of the floor. Liza Jane was alive on every dance floor.35

Of course, if one could not hold the stage, someone else would break in, riffing on the songs as they sang them, even in the chorus—even familiar songs with known names like “Virginny Nigger Very Good.” Listeners and singers at the corn-shuckings disdained song leaders who stuttered or ran out of rhymes. The tongues of the enslaved learned to keen or growl or laugh their songs a different way each time through. This was very different from white music and white people’s songs, which stuck to the same lyrics for decades. White musical ensembles played one rhythm at a time, their dancers following steps that might as well have been painted on the floor. White musical culture was a formation that approved those who marched in time. Black culture was a ring, with space in the middle for anyone willing to try his or her step. And by nourishing, practicing, and training themselves in improvisation, enslaved masters of innovation learned to think creatively as new demands and new dangers emerged. To the extent that they could institutionalize anything while living in the midst of white-created chaos, enslaved African Americans made the encouragement of creative individual performance the center of gatherings. At Saturday night dances, “when a brash nigger boy cut a cute bunch of steps, the men folk would give him a dime or so,” even though dimes were scarce.36

Dimes earned in that way, and the love implied by them, had taught Reuben as a boy—had taught him to teach himself. Their equivalent kept teaching him as a man. At the corn-shucking, it was his peers, the ring, who sang the base to guide and bear him up. Even his rivals were the steel on which he sharpened himself. And it was no foregone conclusion that enslaved migrants would support each other in this process, that they would form a ring and clap, or sing the base from which others could improvise. Their traumas could have made them too selfish, too arrogant, too amoral, too self-isolating. They were desperately poor. Enslavers teased them with stolen abundance. On Sunday mornings, remembered George Strickland of his boyhood in Alabama, “they”—white folks—“would give us biscuits for breakfast, which was so rare that we’d try to beat the others out of theirs.” Children fought for the taste of white flour, to the laughter of enslavers, and some enslaved people old enough to know better acted much the same when the music started.37

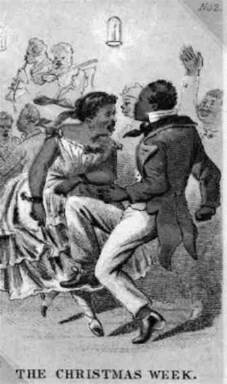

Image 5.2. Dances during the off-times and Saturday nights provided one type of social setting that allowed people divided and measured and sold, forced through what were in effect divorces—though against the will of each party—to perform the gender roles and individual personalities that they believed made them special. “The Christmas Week,” from “Album varieties no. 3; The slave in 1863,” Philadelphia, 1863. Library of Congress.

Yet in musical and social rituals that played out as rings surrounding a changing cast of innovators, enslaved people chose to act in ways that reinforced a sense of individual independence through the reality of mutual interdependence. And those choices mattered. Music can do things to our emotions, our thoughts, and our bodies in ways that analysis of the words of a song like “Liza Jane” cannot encompass. Those were the things about music that could, and did, save lives. Cold metal shackles now bound Reuben’s hands, and he sat silent on the flatboat as the shoreline scrolled by him. But in his tongue, his memory, his spirit, and his spine were well-honed tools. In Louisiana, Reuben would wield once again his power to adapt old songs to new situations: to call out emotions, to urge his coparticipants to merge with and play off each other’s voices and rhythms in greater collective effort that also allowed space for individuals to shine. What they did for themselves would do for him as well. For people made into commodities had a desperate need to resist the ways in which the rapidly changing world treated them like faceless units. Many had the creative capacity to do it, just as many had the creativity to survive the ever-increasing demands made on hands in the field.38

Eventually, white Bohemian communities of artists in Paris and New York and San Francisco would build on Whitman’s ideals of individualism by trying to make life into art and vice versa. But they trailed behind Reuben in many ways, and his depths were deeper. His powers of observation and creation were more powerful, for he knew the weight of iron on his wrists. He drew on the old and the new more effectively, for change had cost him a price the white Bohemians might never comprehend. Nor could the man or woman who was about to buy him understand, and southwestern enslavers who compelled performance—such as the enslavers who forced marching coffles of captives to sing as they marched southwest in the slave trade—even found themselves the objects of ironic imitation. The circle became an opportunity for in-jokes, for sheltering together from the white stare, for facing outward together in defense.39

The circle, of course, became all the more fascinating to whites as it grew more impenetrable. Whites’ belief that there was a distinct “Negro music” helped shape another commodity: this one something that some whites wanted to possess and inhabit as a put-on self. It began with a few black performers who had made their way to the North as sailors on cotton vessels. They became a sensation in New York’s working-class theaters, playing their banjos, singing, dancing, and clapping rhythms with their hands and feet. In the increasingly fast-paced and novelty-seeking culture of commercializing cities, the impact of black performance was shocking yet entrancing. White men— including many working-class ones who had worked in the South as functionaries of the expanding cotton empire—began to imitate and demonstrate what they had learned on the Ohio River or in New Orleans. Former cotton-gin mechanics, flatboat pilots, and apprentice clerks sang, bucked, and jived while frailing their banjos in the most authentic way, often while (weirdly) blacked-up, “playing Negro.”40

It was very strange for such white men to sing “Oh, Susanna, don’t you cry for me”—the story of an enslaved man trying to find his true love, who’d been taken to New Orleans—when the losses of a million Susannas made jobs for such white men. But as these white imitators created the minstrel show genre, and “Oh, Susanna,” the most popular song of 1847–1848, made Stephen Foster the nation’s first professional songwriter, blackface became the quintessential American popular entertainment of the nineteenth century. Blackface also became the archetypal model for how non-black performers would sell a long series of innovations created by enslaved migrants and their descendants—ragtime, jazz, blues, country, rhythm and blues, rock and roll, soul, and hip-hop—to a white market. From that time forward, many whites saw African-American song and dance as mere instinct, and have not understood that it is really deep art in control of complex passion. That art took shape in the creation of new ways to talk and to sing and to dance, it took shape on the cotton frontier, and it took shape in the loss and transcendence that lies seven hundred miles deep in the words of “Old Virginia, Never Tire”—a song first sung by men and women whose personal histories pivoted around the endlessly repeated march from Virginia to the new ground. But over time, iterations and recombinations of what enslaved migrants created on the cotton and sugar frontiers gave birth to American and then global popular music. Musical elements from African cultural traditions surely explain some of this appeal, but what African Americans did to always make those roots new on slavery’s frontiers made this musical tradition uniquely attractive.41

CHARLES BALL HAD EXPERIENCED the full array of devastations practiced upon his body and his life by the new kind of slavery growing on the South’s frontiers. He contemplated the choice that almost swallowed up Lucy Thurston, whose first few weeks in the Louisiana field had been the death-in-life of the zombie. Like Lucy, Ball chose otherwise. Perhaps his survival, and perhaps Thurston’s as well, were miracles. Then again, there were times when to those who struggled on, death seemed more merciful than these resurrections. But just as Lucy ended up singing with the men in the fields on Friday, on a Saturday night in 1805 Charles Ball danced until dawn in the yard between the slave cabins. Several men took turns playing the banjo. Everyone sang. The older people soon grew too tired to dance but they still beat rhythms with their hands. When the music slowed to a pause, they told stories of Africa. “A man cannot well be miserable, when he sees every one about him immersed in pleasure,” Ball remembered. “I forgot for the time, all the subjects of grief that were stored in my memory, all the acts of wrong that had been perpetrated against me.”

Дата добавления: 2015-09-04; просмотров: 62 | Нарушение авторских прав

| <== предыдущая страница | | | следующая страница ==> |

| TONGUES 1 страница | | | TONGUES 3 страница |