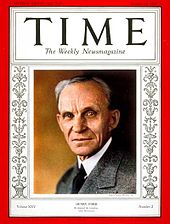

Time Magazine, January 14, 1935.

Ford was a pioneer of "welfare capitalism", designed to improve the lot of his workers and especially to reduce the heavy turnoverthat had many departments hiring 300 men per year to fill 100 slots. Efficiency meant hiring and keeping the best workers.[22]

Ford astonished the world in 1914 by offering a $5 per day wage ($120 today), which more than doubled the rate of most of his workers.[23] A Cleveland, Ohio newspaper editorialized that the announcement "shot like a blinding rocket through the dark clouds of the present industrial depression."[24] The move proved extremely profitable; instead of constant turnover of employees, the best mechanics in Detroit flocked to Ford, bringing their human capital and expertise, raising productivity, and lowering training costs.[25][26] Ford announced his $5-per-day program on January 5, 1914, raising the minimum daily pay from $2.34 to $5 for qualifying workers. It also set a new, reduced workweek, although the details vary in different accounts. Ford and Crowther in 1922 described it as six 8-hour days, giving a 48-hour week,[27] while in 1926 they described it as five 8-hour days, giving a 40-hour week.[28] (Apparently the program started with Saturday being a workday and sometime later it was changed to a day off.)

Detroit was already a high-wage city, but competitors were forced to raise wages or lose their best workers.[29] Ford's policy proved, however, that paying people more would enable Ford workers to afford the cars they were producing and be good for the economy. Ford explained the policy as profit-sharing rather than wages.[30] It may have been Couzens who convinced Ford to adopt the $5-day.[31]

The profit-sharing was offered to employees who had worked at the company for six months or more, and, importantly, conducted their lives in a manner of which Ford's "Social Department" approved. They frowned on heavy drinking, gambling, and (what today are called) deadbeat dads. The Social Department used 50 investigators, plus support staff, to maintain employee standards; a large percentage of workers were able to qualify for this "profit-sharing."

Ford's incursion into his employees' private lives was highly controversial, and he soon backed off from the most intrusive aspects. By the time he wrote his 1922 memoir, he spoke of the Social Department and of the private conditions for profit-sharing in the past tense, and admitted that "paternalism has no place in industry. Welfare work that consists in prying into employees' private concerns is out of date. Men need counsel and men need help, often special help; and all this ought to be rendered for decency's sake. But the broad workable plan of investment and participation will do more to solidify industry and strengthen organization than will any social work on the outside. Without changing the principle we have changed the method of payment."[32]

Labor unions

Ford was adamantly against labor unions. He explained his views on unions in Chapter 18 of My Life and Work. [33] He thought they were too heavily influenced by some leaders who, despite their ostensible good motives, would end up doing more harm than good for workers. Most wanted to restrict productivity as a means to foster employment, but Ford saw this as self-defeating because, in his view, productivity was necessary for any economic prosperity to exist.

He believed that productivity gains that obviated certain jobs would nevertheless stimulate the larger economy and thus grow new jobs elsewhere, whether within the same corporation or in others. Ford also believed that union leaders had a perverse incentive to foment perpetual socio-economic crisis as a way to maintain their own power. Meanwhile, he believed that smart managers had an incentive to do right by their workers, because doing so would maximize their own profits. (Ford did acknowledge, however, that many managers were basically too bad at managing to understand this fact.) But Ford believed that eventually, if good managers such as he could fend off the attacks of misguided people from both left and right (i.e., both socialists and bad-manager reactionaries), the good managers would create a socio-economic system wherein neither bad management nor bad unions could find enough support to continue existing.

To forestall union activity, Ford promoted Harry Bennett, a former Navy boxer, to head the Service Department. Bennett employed various intimidation tactics to squash union organizing.[34] The most famous incident, on May 26, 1937, involved Bennett's security men beating with clubs UAW representatives, including Walter Reuther.[35] While Bennett's men were beating the UAW representatives, the supervising police chief on the scene was Carl Brooks, an alumnus of Bennett’s Service Department, and [Brooks] "did not give orders to intervene."[36] The incident became known as The Battle of the Overpass.

In the late 1930s and early 1940s, Edsel (who was president of the company) thought Ford had to come to some sort of collective bargaining agreement with the unions because the violence, work disruptions, and bitter stalemates could not go on forever. But Henry (who still had the final veto in the company on a de facto basis even if not an official one) refused to cooperate. For several years, he kept Bennett in charge of talking to the unions that were trying to organize the Ford Motor Company. Sorensen's memoir[37] makes clear that Henry's purpose in putting Bennett in charge was to make sure no agreements were ever reached.

The Ford Motor Company was the last Detroit automaker to recognize the United Auto Workers union (UAW). A sit-down strike by the UAW union in April 1941 closed the River Rouge Plant. Sorensen recounted[38] that a distraught Henry Ford was very close to following through with a threat to break up the company rather than cooperate, but his wife Clara told him she would leave him if he destroyed the family business. In her view, it would not be worth the chaos it would create. Henry complied with his wife's ultimatum, and even agreed with her in retrospect.[38] Overnight, the Ford Motor Company went from the most stubborn holdout among automakers to the one with the most favorable UAW contract terms.[38] The contract was signed in June 1941.[38]

Дата добавления: 2015-10-26; просмотров: 119 | Нарушение авторских прав

| <== предыдущая страница | | | следующая страница ==> |

| Ford Motor Company | | | The coming of World War II and Ford's mental collapse |