|

Читайте также: |

Under what conditions would we be justified in assuming that a given postbiotic system has conscious experience? Or that it also possesses a conscious self and a genuine consciously experienced first-person perspective? What turns an information-processing system into a subject of experience? We can nicely sum up these questions by asking a simpler and more provocative one: What would it take to build an artificial Ego Machine?

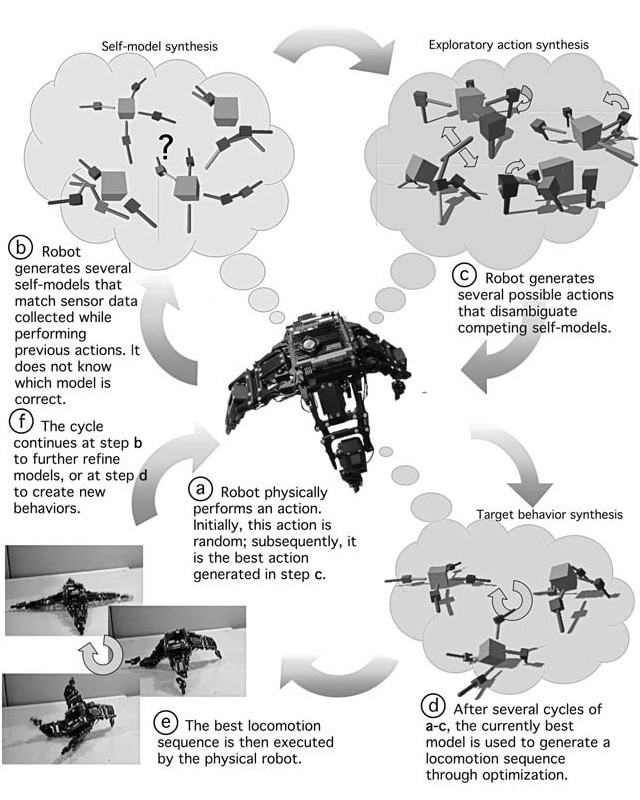

Figure 17b: The robot continuously cycles through action execution. (A and B) Self-model synthesis. The robot physically performs an action (A). Initially, this action is random; later, it is the best action found in (C). The robot then generates several self-models to match sensor data collected while performing previous actions (B). It does not know which model is correct. (C) Exploratory action synthesis. The robot generates several possible actions that disambiguate competing self-models. (D) Target behavior synthesis. After several cycles of (A) to (C), the best current model is used to generate locomotion sequences through optimization. (E) The best locomotion sequence is executed by the physical device. (F)4

Being conscious means that a particular set of facts is available to you: that is, all those facts related to your living in a single world. Therefore, any machine exhibiting conscious experience needs an integrated and dynamical world-model. I discussed this point in chapter 2, where I pointed out that every conscious system needs a unified inner representation of the world and that the information integrated by this representation must be simultaneously available for a multitude of processing mechanisms. This phenomenological insight is so simple that it has frequently been overlooked: Conscious systems are systems operating on globally available information with the help of a single internal model of reality. There are, in principle, no obstacles to endowing a machine with such an integrated inner image of the world and one that can be continuously updated.

Another lesson from the beginning of this book was that, in its very essence, consciousness is the presence of a world. In order for a world to appear to it, an artificial Ego Machine needs two further functional properties. The first consists of organizing its internal information flow in a way that generates a psychological moment, an experiential Now. This mechanism will pick out individual events in the continuous flow of the physical world and depict them as contemporaneous (even if they are not), ordered, and flowing in one direction successively, like a mental string of pearls. Some of these pearls must form larger gestalts, which can be portrayed as the experiential content of a single moment, a lived Now. The second property must ensure that these internal structures cannot be recognized by the artificial conscious system as internally constructed images. They must be transparent. At this stage, a world would appear to the artificial system. The activation of a unified, coherent model of reality within an internally generated window of presence, when neither can be recognized as a model, is the appearance of a world. In sum, the appearance of a world is consciousness.

But the decisive step to an Ego Machine is the next one. If a system can integrate an equally transparent internal image of itself into this phenomenal reality, then it will appear to itself. It will become an Ego and a naive realist about whatever its self-model says it is. The phenomenal property of selfhood will be exemplified in the artificial system, and it will appear to itself not only as being someone but also as being there. It will believe in itself.

Note that this transition turns the artificial system into an object of moral concern: It is now potentially able to suffer. Pain, negative emotions, and other internal states portraying parts of reality as undesirable can act as causes of suffering only if they are consciously owned. A system that does not appear to itself cannot suffer, because it has no sense of ownership. A system in which the lights are on but nobody is home would not be an object of ethical considerations; if it has a minimally conscious world model but no self-model, then we can pull the plug at any time. But an Ego Machine can suffer, because it integrates pain signals, states of emotional distress, or negative thoughts into its transparent self-model and they thus appear as someone’s pain or negative feelings. This raises an important question of animal ethics: How many of the conscious biological systems on our planet are only phenomenalreality machines, and how many are actual Ego Machines? How many, that is, are capable of the conscious experience of suffering? Is RoboRoach among them? Or are only mammals, such as the macaques and kittens, sacrificed in consciousness research? Obviously, if this question cannot be decided for epistemological reasons, we must make sure always to err on the side of caution. It is precisely at this stage of development that any theory of the conscious mind becomes relevant for ethics and moral philosophy.

An Ego Machine is also something that possesses a perspective. A strong version should know that it has such a perspective by becoming aware of the fact that it is directed. It should be able to develop an inner picture of its dynamical relations to other beings or objects in its environment, even as it perceives and interacts with them. If we do manage to build or evolve this type of system successfully, it will experience itself as interacting with the world — as attending to an apple in its hand, say, or as forming thoughts about the human agents with whom it is communicating. It will experience itself as directed at goal states, which it will represent in its self-model. It will portray the world as containing not just a self but a perceiving, interacting, goal-directed agent. It could even have a high-level concept of itself as a subject of knowledge and experience.

Anything that can be represented can be implemented. The steps just sketched describe new forms of what philosophers call representational content, and there is no reason this type of content should be restricted to living systems. Alan M. Turing, in his famous 1950 paper “Computing Machinery and Intelligence,” made an argument that later was condensed thus by distinguished philosopher Karl Popper in his book The Self and Its Brain, which he coauthored with the Nobel Prize– winning neuroscientist Sir John Eccles. Popper wrote: “Specify the way in which you believe a man is superior to a computer and I shall build a computer which refutes your belief. Turing’s challenge should not be taken up; for any sufficiently precise specification could be used in principle to programme a computer.”6

Of course, it is not the self that uses the brain (as Karl Popper would have it) — the brain uses the self-model. But what Popper clearly saw is the dialectic of the artificial Ego Machine: Either you cannot identify what exactly about human consciousness and subjectivity cannot be implemented in an artificial system or, if you can, then it is just a matter of writing an algorithm that can be implemented in software. If you have a precise definition of conciousness and subjectivity in causal terms, you have what philosophers call a functional analysis. At this point, the mystery evaporates, and artificial Ego Machines become, in principle, technologically feasible. But should we do whatever we’re able to do?

Here is a thought experiment, aimed not at epistemology but at ethics. Imagine you are a member of an ethics committee considering scientific grant applications. One says:

We want to use gene technology to breed mentally retarded human infants. For urgent scientific reasons, we need to generate human babies possessing certain cognitive, emotional, and perceptual deficits. This is an important and innovative research strategy, and it requires the controlled and reproducible investigation of the retarded babies’ psychological development after birth. This is not only important for understanding how our own minds work but also has great potential for healing psychiatric diseases. Therefore, we urgently need comprehensive funding.

No doubt you will decide immediately that this idea is not only absurd and tasteless but also dangerous. One imagines that a proposal of this kind would not pass any ethics committee in the democratic world. The point of this thought experiment, however, is to make you aware that the unborn artificial Ego Machines of the future would have no champions on today’s ethics committees. The first machines satisfying a minimally sufficient set of conditions for conscious experience and selfhood would find themselves in a situation similar to that of the genetically engineered retarded human infants. Like them, these machines would have all kinds of functional and representational deficits — various disabilities resulting from errors in human engineering. It is safe to assume that their perceptual systems — their artificial eyes, ears, and so on — would not work well in the early stages. They would likely be halfdeaf, half-blind, and have all kinds of difficulties in perceiving the world and themselves in it — and if they were true artificial Ego Machines, they would, ex hypothesi, also be able to suffer.

If they had a stable bodily self-model, they would be able to feel sensory pain as their own pain. If their postbiotic self-model was directly anchored in the low-level, self-regulatory mechanisms of their hardware — just as our own emotional self-model is anchored in the upper brainstem and the hypothalamus — they would be consciously feeling selves. They would experience a loss of homeostatic control as painful, because they had an inbuilt concern about their own existence. They would have interests of their own, and they would subjectively experience this fact. They might suffer emotionally in qualitative ways completely alien to us or in degrees of intensity that we, their creators, could not even imagine. In fact, the first generations of such machines would very likely have many negative emotions, reflecting their failures in successful self-regulation because of various hardware deficits and higher-level disturbances. These negative emotions would be conscious and intensely felt, but in many cases we might not be able to understand or even recognize them.

Take the thought experiment a step further. Imagine these postbiotic Ego Machines as possessing a cognitive self-model — as being intelligent thinkers of thoughts. They could then not only conceptually grasp the bizarreness of their existence as mere objects of scientific interest but also could intellectually suffer from knowing that, as such, they lacked the innate “dignity” that seemed so important to their creators. They might well be able to consciously represent the fact of being only secondclass sentient citizens, alienated postbiotic selves being used as interchangeable experimental tools. How would it feel to “come to” as an advanced artificial subject, only to discover that even though you possessed a robust sense of selfhood and experienced yourself as a genuine subject, you were only a commodity?

The story of the first artificial Ego Machines, those postbiotic phenomenal selves with no civil rights and no lobby in any ethics committee, nicely illustrates how the capacity for suffering emerges along with the phenomenal Ego; suffering starts in the Ego Tunnel. It also presents a principled argument against the creation of artificial consciousness as a goal of academic research. Albert Camus spoke of the solidarity of all finite beings against death. In the same sense, all sentient beings capable of suffering should constitute a solidarity against suffering. Out of this solidarity, we should refrain from doing anything that could increase the overall amount of suffering and confusion in the universe. While all sorts of theoretical complications arise, we can agree not to gratuitously increase the overall amount of suffering in the universe — and creating Ego Machines would very likely do this right from the beginning. We could create suffering postbiotic Ego Machines before having understood which properties of our biological history, bodies, and brains are the roots of our own suffering. Preventing and minimizing suffering wherever possible also includes the ethics of risktaking: I believe we should not even risk the realization of artificial phenomenal self-models.

Our attention would be better directed at understanding and neutralizing our own suffering — in philosophy as well as in the cognitive neurosciences and the field of artificial intelligence. Until we become happier beings than our ancestors were, we should refrain from any attempt to impose our mental structure on artificial carrier systems. I would argue that we should orient ourselves toward the classic philosophical goal of self-knowledge and adopt at least the minimal ethical principle of reducing and preventing suffering, instead of recklessly embarking on a second-order evolution that could slip out of control. If there is such a thing as forbidden fruit in modern consciousness research, it is the careless multiplication of suffering through the creation of artificial Ego Tunnels without a clear grasp of the consequences.

Дата добавления: 2015-10-31; просмотров: 157 | Нарушение авторских прав

| <== предыдущая страница | | | следующая страница ==> |

| ARTIFICIAL EGO MACHINES | | | BLISS MACHINES: IS CONSCIOUS EXPERIENCE A GOOD IN ITSELF? |